I think it is important to get to know the art of the Muslim peoples of the Caucasus more closely. There is a lot of original knowledge and cultural synthesis in this region. I became particularly interested in Dagestan when I first saw the tombstones in Kala Quraish. Caleb Schmidt and I had the opportunity to have a bird’s eye view of the art and culture of Dagestan.

Let’s start by getting to know you.

My name is Caleb, I live in the capital of Dagestan, in the city of Makhachkala. I am an artist, a collector, and I am also engaged in the development of children’s creativity in the mountains of Dagestan, I have my own summer school for rural children.

Ornaments and the sacred meaning embedded in them, attracted me since childhood. I remember how my grandmother, when we walked around our ancestral village, showed me different ornaments on the facades of houses, ancient necropolises, and told me about the semantic meaning of this or that ornament. Each ornament has a deep perspective, for example, a jug symbolizes the purity of the soul, like water in this jug, the personification of beauty in ancient times is long hair, braids, accordingly, to denote beauty, a comb was depicted. On the facades of houses, you can most often find protective and good whish, for example, images of predatory animals, prayers from the Holy Quran.

A year ago I was on an expedition to mountainous Dagestan and created a unique collection of prints from various reliefs and surfaces. This expedition was for me a kind of pilgrimage to my heritage, I wanted to show the younger generation how rich Dagestan is in ornamental heritage.

In April of this year I had my first personal exhibition in Makhachkala, there were a lot of people, I did not expect such a big interest in the ornament. Many did not even know that such ornaments are found in Dagestan. Preparations for the exhibition took a very long time,

I was very worried, I think I would not have managed it alone, I was helped in organizing the exhibition by the well-known Russian curator and publisher Zarema Dadaeva. My exhibition was called “IKHTILAT” in Dagestan languages it means -dialogue. The concept of my exhibition is that I entered into a certain sacred dialogue in my pilgrimage to the mountains of Dagestan, with the ornamental heritage of my ancestors and the answer received in the form of various ornaments on paper, I demonstrated to my fellow countrymen. This is a certain dialogue between the modern and the past.

The most interesting thing is that the ornaments that are found on necropolises, house facades, etc. can also be found on household items, jewelry, carpets and textiles. This suggests that this ornamental language was not tied to any one type of applied art in the past, it was universal. And sometimes these ornaments are found not only in Dagestan, but all over the world. I think in the past there was a single ornamental language that united many peoples of the world.

What distinguishes the art of Dagestan from the art of other Caucasian peoples?

A distinctive feature of the art of Dagestan, from other Caucasian peoples, is its diversity and versatility. like the peoples inhabiting this region. The art of Dagestan is like a patchwork quilt. In the old days in Dagestan, not a single object could be without ornamental decor, from an ordinary spoon to architectural buildings, everything carried a certain sacred and semantic load.

In my opinion, by giving an ornament to a particular object, the master would conduct an initiation ritual and give an auxiliary function to a particular object, like giving a name to a person. For example, on household items, you can often find an ornament with many parallel lines, this is a symbol of a plowed field, that is, a wish for constant prosperity to the house where the object is located. If now the ornament is perceived as a decorative part, then earlier it carried a deep sacred information load and could not be used just like that. This tradition differs from the simple subordination of the decor to the form and function of the product, and represents a more complex relationship.

What is the significance of Kala Quraish and can you tell us about the calligraphic styles and symbols on the tombstones there?

Kala Koreysh is one of the diamonds in the crown of Dagestan. It is precisely a diamond, because it has not been cut, the true potential of this object, like many other objects on the territory of Dagestan, has not yet been revealed. Many villages of Dagestan have a huge cultural and historical layer; each village has its own unique style and language of art.

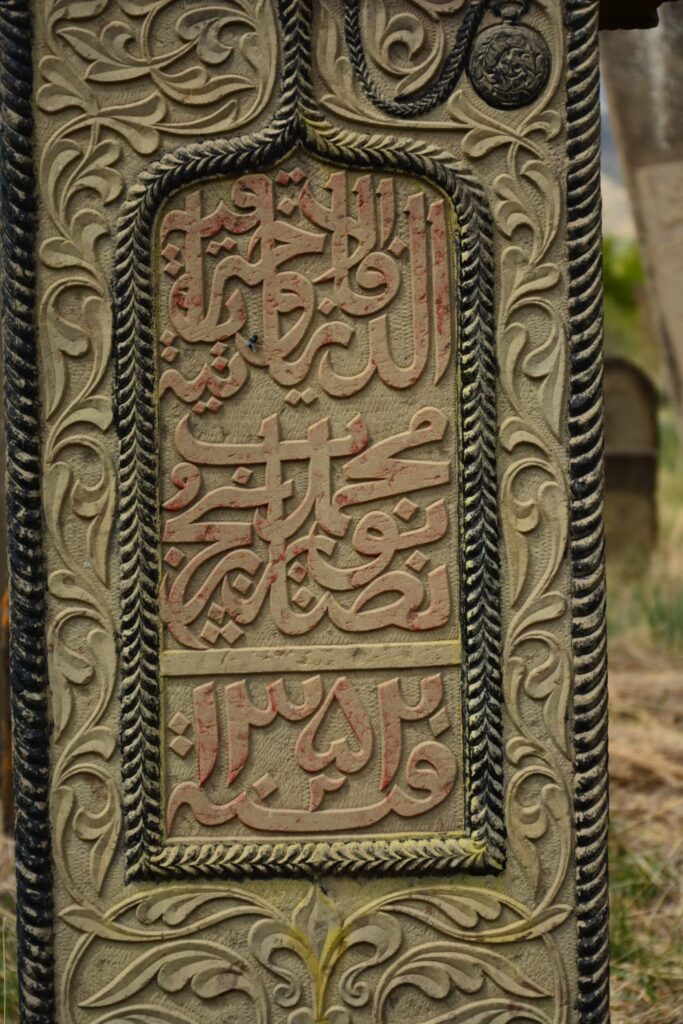

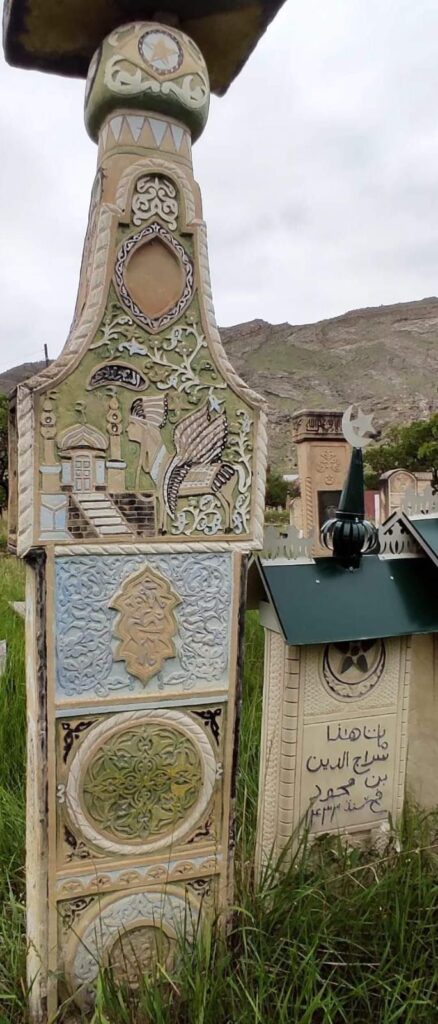

For example, in the medieval capital of the Kaitag possession – Kala-Koreisha and in some other places, the styles of Arabic calligraphy sulus, Nastaliq, etc., which are not typical for the rest of Dagestan, are found transformed into stone stele. This is due to the fact that Qala Koreish and other places were in close cultural, economic and politic ties with Iran and other progressive cultural and political centers of the East.

Despite the dominance of one or another art style in the region, Dagestan masters rethought and adjusted this art to the local understanding of aesthetics and achieved high skill in execution. Tombstones in Dagestan carry a very large and interesting meaning.

For example, by the form of execution, ornamental composition, you can learn a lot about a person – what gender, social status, profession, etc. On tombstones, plant patterns and motifs are used as the main decorative composition. This is a reference to the Gardens of Eden and the ideas of eternal peace in the Abrahamic religions.

Sometimes in an ornamental composition, you can find ornaments borrowed from objects that the master liked. For example, an ornament from silk damask brocade, a traditional Chinese ornament, etc. I think this was connected with the Great Silk Road, luxurious expensive items came to the region, and the masters found the ornaments on these products semantically close and copied them in their work. Very often in Dagestan, varieties of swastika are found on carpets, on stones and other objects of applied art, and this is one of the symbols of Buddhism. Despite the fact that this symbol is found on many continents, we can only guess how this symbol appeared on the territory of Dagestan and what role it played in the culture and worldview of the people.

Of particular interest is also the tradition of painting reliefs on tombstones; this tradition, in addition to its decorative function, also has a deep sacred meaning; by covering one or another ornament with paint, the craftsmen highlighted it from the overall composition, thereby showing some respect for the exquisite Arabic font, intricate floral patterns and other carved elements on the stone. The paint also protected the stone from moisture penetration and external influences. Sometimes, on tombstones, carved stones from the facade of the house and other objects, you can find pre-Islamic symbolism that harmoniously fits into the main decor. This, in my opinion, is due to the fact that craftsmen sometimes copied the ornament they liked from more ancient stones and reliefs.

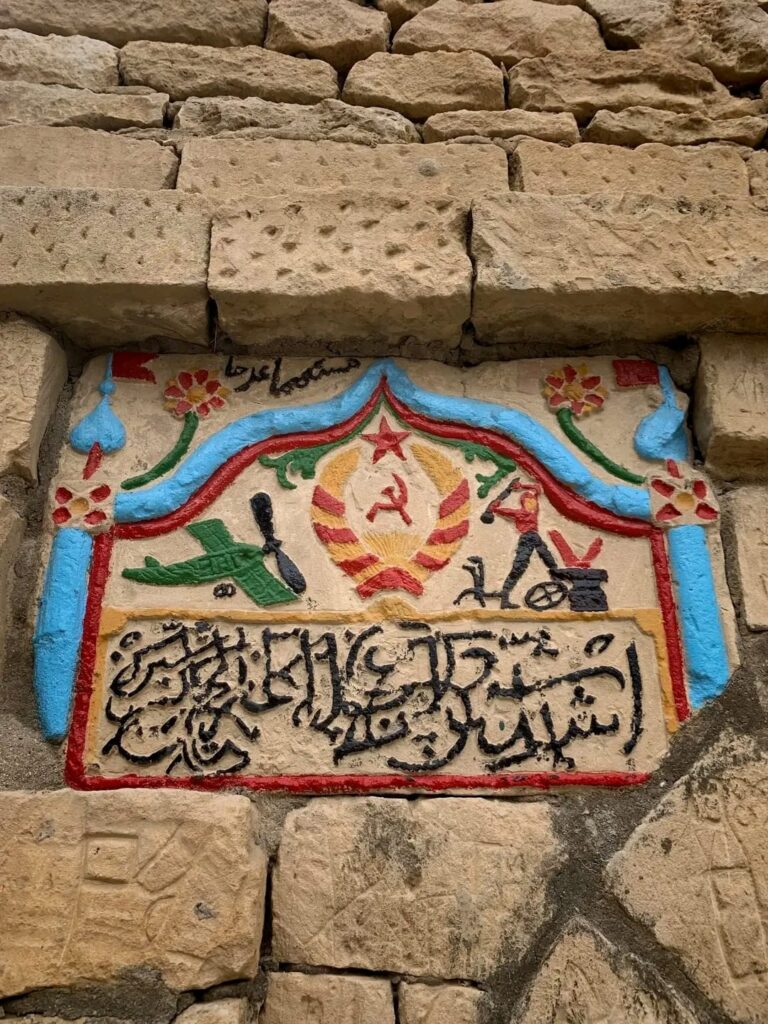

What is the tradition of inscriptions in Dagestan? I have seen inscriptions with Arabic letters from the Soviet era.

You can find two antagonists in the composition of an ornament, for example, Soviet symbolism and Islamic symbolism, which would be completely incompatible things, but art erases the boundaries and creates a harmonious storyline. This is very philosophically deep.

For me, from the point of view of art and the transformation of public thinking and life, objects of applied art created in a short period of time from about 1917 to 1932 are of interest. This is the era of the new Soviet power, where old ideals and values were overthrown from Olympus and new ones were erected. A turning point in the history of not only Dagestan, but the entire country. Soviet symbols are found on art objects – a sickle and hammer, the Kremlin tower, etc. and around the text and slogans adjam based on Arabic letters, isn’t this a very interesting detail? The fact is that the reforms in the field of writing in the region during the Soviet period were quite difficult, since the peculiarity of local languages and phonetics prevented the introduction of the new alphabet. And the tradition of adjam based on the Arabic alphabet was preserved for some time in Soviet times, until a new alphabet based on the Cyrillic alphabet appeared.

Ornaments on carved stones and other objects of applied art can tell not only about religious and aesthetic ideas at a given period of time in the history of a people, but also tell a lot about economic, political and other relationships between peoples. These are entire libraries that have preserved a large layer of information.

There are Dagestan manuscripts found in many parts of the world. Can you tell us about the manuscripts and Dagestan calligraphy styles?

With the development of Arabic culture and writing, the need arose to adapt Arabic letters to the needs of local languages. This is how the Ajam writing appeared; the first attempts to adapt the Arabic alphabet to local languages have been known since the 15th-16th centuries, but the final formation of the Ajam writing dates back to the beginning of the 18th century, which lasted until 1928. This process is associated with the emergence of the first literary monuments in the native languages of the Dagestan peoples. The development of ajam contributed to the creation of a significant cultural heritage in the languages of the peoples of Dagestan, including works of fiction, historical chronicles, etc., as well as the emergence of book publishing.

In the past, book publishing was developed in Dagestan; in each village, there were libraries at mosques, and anyone could access them. The tradition of rewriting manuscripts was very developed; it was considered respectful if a good calligrapher rewrote the Holy Quran. The literacy rate of the population was high; children were taught to read and write from childhood by sending them to rural madrassas. In addition to theological knowledge, students received basic knowledge of mathematics, astronomy, etc. Those who wanted to continue gaining knowledge went to large cultural and economic centers of Dagestan such as Gazi-Kumukh, Derbent, Akusha, etc., where they looked for teachers and mentors. Sometimes, in search of knowledge, Dagestanis went to other countries – Syria, Egypt, etc. Ajam played a huge role in cultural and social life, being a link between different tribes in Dagestan. Unfortunately, during the civil war, for ideological reasons, a huge cultural layer of the old world was destroyed, priceless libraries with manuscript collections were burned, religious and other architectural structures were destroyed. Despite this, valuable manuscripts, which today are a national treasure, miraculously survived in Dagestan. In many countries, you can find fragments of the manuscript and cultural heritage of Dagestan scientists and thinkers, for example, in the US, the Princeton University library contains 130 books from the personal library of Imam Shamil (leader of the North Caucasian national liberation resistance). Among the books are those copied by the young Shamil, who was preparing for a career as a scientist.

What kind of cultural and artistic life is there in Dagestan today?

Today, artistic life in Dagestan maintains its tradition of versatility, a huge number of talented artists are inspired by the rich heritage, rethink and create incredibly deep and unique works. These are such famous names as: Artists – Magomed Kazhlaev, Eduard Puterbrot, Aladdin Garunov, Tavus Makhacheva, Natalie Mali, Apandi Magomedov, Ibragimkhalil Supyanov, Tagir Gapurov, Natalia Savelyeva. Costume designer -Shamkhal Alikhanov, curator and publisher -Zarema Dadaeva, architect -Kamil Tsuntaev and many others. All of them have their own original author’s style, and in their work, projects are inspired by the cultural heritage that Dagestan has.