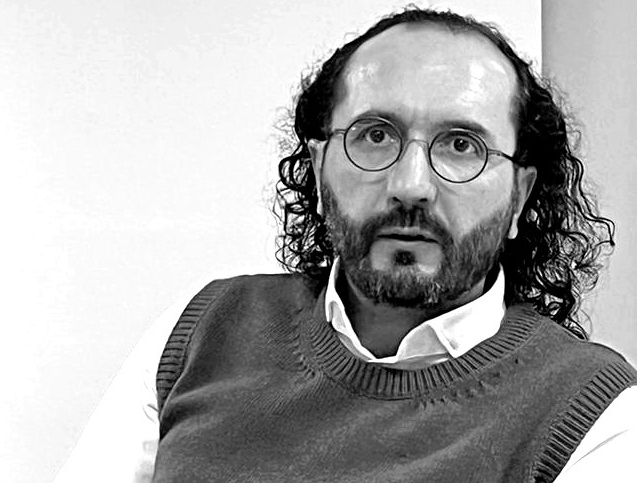

I got to know Bülent Tokgöz through his book Cihadın Mahrem Hikayesi (The Confidential Story of Jihad). What makes the book unique is that it conveys the story to us from the perspective of a mujahid, revealing everything from the inside with stark clarity. He has 15 books in total. In his 5-volume series Büyük Oyundan Dersler (Lessons from the Great Game), he offers an original perspective on events happening in the Islamic world, covering topics such as the Israel-Iran tension. We spoke about Iran and its expansionism, which became relevant once again after the recent Israel-Iran escalation.

Your book, Cihadın Mahrem Hikayesi, is very important in helping us understand both the global jihad movements and the psychological dynamics behind them. I was surprised to read about Iran’s expansion there during the Bosnian War. People rarely mentioned that aspect of the war. What is Iran doing in jihad territories, and what does it aim for?

Bosnia is a faraway place; it was even farther for our ancestors, with a difficult and arduous route—hard even just for a journey. Even with today’s technology, the road is still long. It was even farther for Iran in every sense—geographically, historically, and culturally. While the fire of the Revolution was still fairly fresh, arriving in a region monitored by so many Western countries was, before anything else, a daring move. They had very few footholds, but many enemies and rivals. Despite that, they came, and in my opinion, they were the most successful team. I’m saying this in comparison to the other Islamist groups. In fact, we can say they showed success comparable to the Western powers’ ability to penetrate the post-war order. In this context, among the powers calculating for influence in Bosnia, it is certain that Iran was among the most successful. I believe they more than achieved their goals—perhaps even beyond what they themselves expected.

Historically, they were in a land very distant and foreign to them, effectively in the Turks’ backyard, but they arrived by circumventing the Turks. At that time, the Turks were busy stamping out what they saw as backward-religious-fanatical elements within themselves, so they were mentally and politically too far removed to pay attention to the atrocities the Serbs were committing. An anti-religious psychosis similar to that in the early days of the Republic had reemerged; on one hand, it was deeply sordid, on the other, it was a very sophisticated set of scenarios occupying the national agenda in order to pit the state against the nation. Özal could have been an advantage—he might have lifted his head and paid attention to what was going on in Bosnia—but neither the state’s desire nor its will nor capacity was there. The Republic’s disposition of rejecting its own legacy was in full force, and paramilitary gangs had already effectively deposed Özal with the intention of taking him out politically.

During the ’90s, while Iran was orchestrating sensational political assassinations in Turkey one after another to deepen the rift between the state and society—playing with the country’s nerve endings and working tirelessly to create perfect conditions for the February 28 coup—it was also busy embracing domestic Islamists whom it had weakened, presenting itself as a savior against their own state. Beyond Turkey’s borders, it was extremely eager, in all the regions the Turks had turned their backs on and neglected, to seize the legacy that the Turks had cast aside. Bosnia was just one of the targets of this initiative and ambition.

“What did it aim for?” The same thing it aims for in other regions: to Shi‘itize Muslims. I say Muslims, rather than Sunnis, because saying “to Shi‘itize Sunnis” wouldn’t have the same impact. In truth, they don’t really have any quarrel with non-Muslims; their main contention is with Muslims, particularly Sunnis. For anyone who knows Shi‘i ideology and its character, it’s unquestionably true that their fights against the USA and Zionists are secondary matters and mere temporary interludes doomed eventually to close.

Shi‘ism has nothing to say to a non-Muslim. They might say, “Did you know Yazid killed the Prophet’s grandson!” and the non-Muslim would respond, “So what? Why should I care?” But a Muslim doesn’t have that luxury; he can’t remain indifferent to the subsequent statements on this issue. Therefore, in non-Muslim quarters, there’s no buyer for “the distinguished wares of Shi‘ism,” but long lines form in Muslim neighborhoods. These things have been studied; they’ve worked on them for centuries. When we hear “Shi‘a,” we imagine a sect formation that’s as haphazard as ours—“set it loose and let God provide.” We do not grasp that it’s actually an enormous organization on the model of the Vatican. Simply by virtue of our naïveté, we represent an enticing prey for them.

Shi‘itization was one dimension of the effort. There were also political aspects. The war would end eventually, and they could market whatever support and assistance they provided during the war with maximum propaganda to the Islamic world. That would become a secondary goal that fortified the first one. On the other hand, a civil society and state structure in which pro-Iran cadres were influential could strengthen Iran’s position in negotiations with the West after the war. Influence over such a sensitive minority in such a sensitive region as the Balkans could be a much stronger bargaining chip than expected. If one recalls that a world war began on a narrow bridge in Sarajevo, the point I’m making becomes clearer.

There was also a military dimension. Because of the structure of the Revolution, Iran had to be a state that could launch armed actions at any time, anywhere. They were not so inexperienced as to attempt grandiose operations against European countries, but they placed great importance on executing or abducting anti-revolutionary opponents who had fled there. At the very least, they needed people who could track them and pass on information—individuals who wouldn’t draw the attention of their opponents and enemies. People who could appear as tourists in faraway lands under different guises, gather information for Iran, and function as couriers for any kind of material. As far as I can tell, Iran was interested in the human factor of Bosnia.

Moreover, they were eager to show their adversaries—the U.S. and the U.K., who were also present in the region—what they were capable of on the ground. It was a kind of deterrence and a show of force that could shift power balances in their favor. Engaging with them, clashing, creating friction, and carrying the tension there could also be a provocative opportunity for Iran’s deep state to develop itself further. As a country that had carried out the Revolution, held its own against Iraq, and equipped numerous organizations here and there in Lebanon, it had no reason to act timidly. The fields were open to them, and they had the necessary players, coaches, money, and drive to play. These were holistic attributes no one else possessed.

Your Büyük Oyundan Dersler (Lessons from the Great Game) series, in its 5th volume, deals with Sunnis and Shi‘as. As far as I know, it’s the only book in Turkey on Iranian expansion in Pakistan. What is Iran’s objective in the region, particularly in Pakistan and Afghanistan?

Both are very important geographies. First of all, they are extremely valuable because of their Shi‘i populations. After Iran, Pakistan is the country with the largest Shi‘i population. We’re talking about a country that possesses the atomic bomb. For an Iran that has close strategic alliances with China and India, having a Shi‘i leverage in Pakistan that could influence what happens in those states is an immeasurably important strategic advantage—one that can be signaled simply by implication. Pakistan is a country that can shape the game with its own unique potential, and thanks to its ability to exert influence, Iran aims to ensure that this game-shaping power doesn’t turn against it. Even just to keep the Sunni Baluch on both sides of the border under control, Pakistan is vital to Iran—non-negotiable.

Afghanistan is a completely different story. Throughout the ’80s, during the Soviet occupation, Iran was the second destination (after Pakistan) for millions of refugees fleeing Afghanistan. In particular, Shi‘i Hazaras headed for Iran. Their fate was directly linked to Iran’s own. Afghanistan wasn’t going to settle down quickly, and sending these millions of people back to their country wouldn’t be possible anytime soon. Although Iran wasn’t particularly hospitable or welcoming to its co-religionists, it still made them stay long enough to process them thoroughly, transforming them into its own likeness before sending them back. It formed militias among their youth who were passionate supporters of the regime. Enduring so many refugees was worthwhile if it meant ending up with thousands of armed militants at the center of Afghanistan who were loyal to Iran.

Wherever the world order was being shaped, a hungry power like Iran had to be present. In the 2000s, it reaped great rewards from this, indeed. While Americans were pondering which Taliban targets to bomb in Afghanistan and how, they consulted Iranian field operatives who were quite experienced. As the American counterpart drooled over the marked-up map laid on the table and asked, “May I take a photo of this?” the Iranian intelligence officer would leave the room with swagger: “You can keep it!”

They benefited greatly from that map and many others. The Americans inadvertently paved the way for Iran to become one of the strongest covert actors in Afghanistan, at least until the Taliban took over. The same obscene drama played out in Iraq. Admittedly, Iran performed skillfully and gave the role its due. The thousands of young people and millions of fanatical extras who died for the cause didn’t grasp or explain a thing, mesmerized by pompous slogans and marches. Persian strategists and Shi‘i eulogy reciters worked in perfect synchronization.

How does Iran manage to turn Sunnis into Shi‘as? And under the banner of Muslim unity (Ummah-ism, Ittihad-ı İslam), how does Iran create space for itself?

They sell spinach to spinach-sellers—simply put, this is their job. They’ve been doing this for centuries, and they’ve never been stronger. This opportunity has been provided to them. They’ve been granted the prestige of a revolution. They’ve been made the champions of anti-imperialism. Anti-Zionism, too, is now associated with them. Their rhetoric is stronger than anything the confused and scrappy actors of the Sunni world can muster. The Muslim Brotherhood (Ikhwan al-Muslimin) was their toughest rival, so they set out early on to bring them into line, and in many places, they succeeded. For instance, Khamenei is someone who had Sayyid Qutb’s works translated into Persian—if indeed he did it himself (though it’s more likely he had one of his many advisors do the actual translation). The key point is that they have the ability to internalize, digest, and surpass that movement. Such confidence and capability by itself furnished them with a force that shifted equations.

Other competitors were the Salafi-Wahhabi camp, who arguably produced the most significant refutations of Shi‘ism. Yet sometimes they’d make moves that were such perfect passes for an overhead kick (so to speak) that one had to doubt their actual intentions. Most importantly, the movement that originated in the deserts of Najd never had a genuine capacity to resonate with the entire Muslim world at even the same level as Shi‘ism. And the fact that the so-called state of Saudi Arabia reeked of British collaboration, American cronyism, and Zionist cooperation meant that any word it uttered would be tainted, indirectly greasing Shi‘ism’s wheel.

The Salafi-Jihadi movement, for its part, targeted Shi‘as with mass killings, driving even the most secular or traditional Shi‘a populations under the umbrella of Khomeinist Shi‘ism. At the moment, there is no truly wise or thoughtful struggle being waged against Shi‘ism. We swing between negligence and heedlessness on one side, or brutality and extremism on the other, and end up passively watching as Shi‘a forces take over their positions. I’m not sure how far or how long the Islamic community will continue to be guided by such ineptitude and obliviousness, considering how much treachery and oppression Iran has inflicted. Those who claim to be vigilant, meanwhile, don’t have enough scholarly acumen, so they end up strengthening the other side.

“How do they create space?” They use taqiyya as the key to open every door. Their counterparts are sound asleep anyway. For the ones who are awake, they employ very effective silencers—money, for example. Our imagination is way too narrow to comprehend the infiltration capacity and actual success that Iran has had in the Sunni world, in Turkey. Not just in the Islamic sector, but in the leftist and Alevi circles, as well as among Kurds; they work diligently and meticulously, and their many shell companies in Turkey do their job well, generously funding their partners. As I wrote in my books, “Being pro-Iran pays well in Turkey.” Now it pays even better. Even when Iran experiences a financial crisis, it continues to support its cadres; it doesn’t leave them dependent on Turks or the Turkish state.

Geographically, Iran is our neighbor. We also have commercial, cultural, and political cooperation. How do you view Turkey-Iran relations?

I love Iran. I love it very much, in fact. No one who is pro-Iran can love it as much as I do, because I see it as my homeland—my homeland before Anatolia. So I do not and cannot view it as an enemy. The Iranian state is not our enemy, nor is the Shi‘i system itself. It’s the Khomeinist regime. As long as that regime remains in place, neither Turks nor other Muslims will find peace. Because the amount of Muslim blood they have shed rivals that of the Crusaders and the Mongols, no matter how much traitors and sellouts try to obscure and distort that.

Turkey’s weaknesses vis-à-vis Iran are countless. Above all, Iran is, in one way or another, a country that takes a stance. It is a state. Turkey, on the other hand, is still trying to become one. Even friends and foes alike see us as a country that vacillates, whose direction is unpredictable from one day to the next, whose strategy is unknown. It’s unclear whether we have any strategic approach at all. In education, how entire generations were ruined and corrupted by endless trial and error is mirrored in foreign policy by zigzags and shortsighted choices that squandered many opportunities. Aside from Azerbaijan’s unique experience, Turkey has not been able to maintain even a balance against Iran, let alone achieve victory, in any arena.

So the question is: Have our state leaders ever even intended to? The secularists, viewing religion and sectarian matters from an outsider’s perspective, see all this as someone else’s business; they can’t be bothered and remain distant from anything that might be used as a tool against Iran. They take refuge in their own version of laicism as a cover for their ignorance and laziness. The Islamic-leaning cadres, on the other hand—by an odd twist—once went through a phase of Iran sympathy, and some of them still remain in that phase, so they balk at the concept of actively opposing Iran. Hence, even when the major showdown began in Syria in the 2010s, Turkey spent much of that time tidying up after Iran, protecting it against the global order. When forced into confrontation, it was always reluctantly, half-heartedly, and extremely cautiously. Breathless, without vision, lacking resolve and seriousness… This is what saddens me the most: Under the Islamic-leaning administration in Turkey, Iran operated like a Trojan horse. The pro-Iran Trojan horses roamed freely. The Turkish state should never have permitted or enabled this. If it had actually functioned as a state, it wouldn’t have.

In one of my books, I compared the foreign policy energy and operational capabilities of Khomeinism and Kemalism, and concluded that Khomeinism would prevail in every way. Turkey hasn’t been able to develop any ideology other than Kemalism. Erdoğan got close to doing so for a while, but for various reasons couldn’t accomplish it. It will be understood more clearly in the future. The cadres who even in Syria wouldn’t go all in against Iran—whether for lack of will or ability—didn’t leave him much recourse, assuming he had wanted to do it in the first place. It’s impossible to generate a favorable momentum in the region while putting on a contradictory, infighting display and polluting our discourse with such amoral or baseless TV dramas and a liberal framework. We are still, in this geography, heirs who squander our inheritance, repudiating our legacy. Iran owes us gratitude; at every step, it repays us with smiles for the new maneuver it executes.