The manuscript decorations of medieval Europe have a unique place among miniature traditions around the world. Manuscript miniatures, which began in monasteries, gradually became a permanent expression of European culture. These works, which include both religious and secular themes, reflect both the social and intellectual structure of the period. Julia Bangert is one of the important artists of this miniature tradition in Europe. For the first time in Turkey, we spoke to her about her art and European miniature.

Let’s start by getting to know you; how did you begin your artistic journey, and what drew you specifically to miniature art?

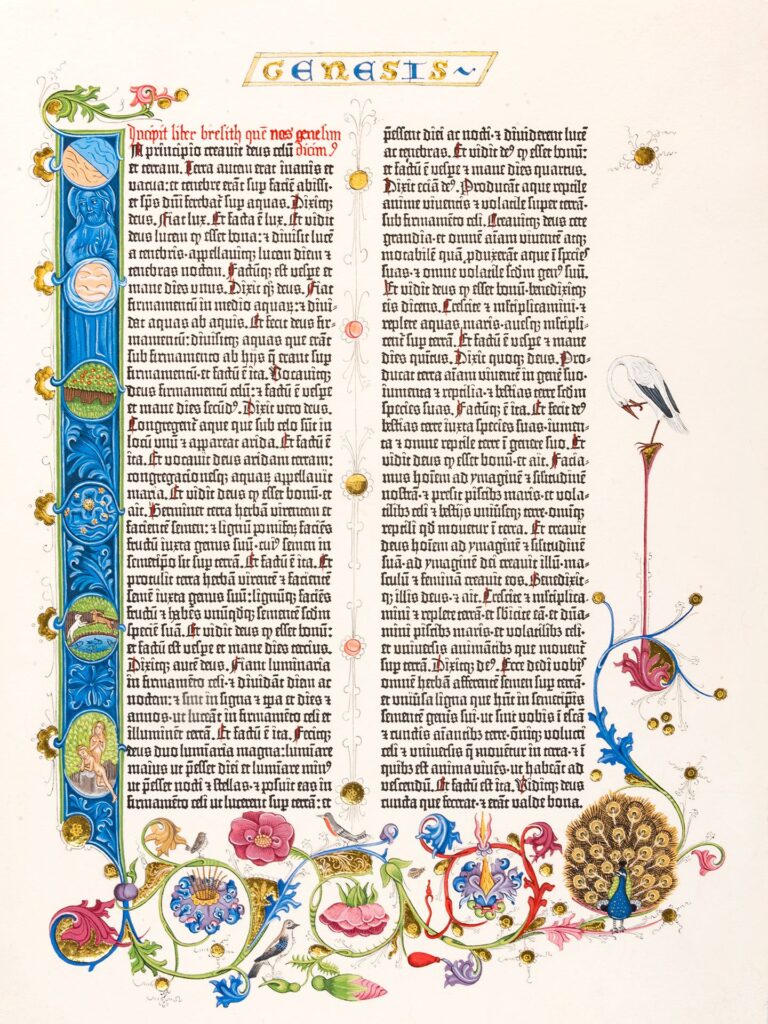

“The whole thing was more or less a coincidence. I’ve always enjoyed painting, but after school I studied book studies, German literature and art history at Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz. Through my studies, I came into contact with the Gutenberg Museum and its funding institutions, the International Gutenberg Society in Mainz and the Gutenberg Foundation. After completing my dissertation on the book trade in the early modern period, I took over the management of the Gutenberg Society and at a joint trade fair appearance at the 2013 Frankfurt Book Fair, I had the opportunity to watch and listen to my colleague from the Gutenberg Foundation as she presented a special product from the Gutenberg Shop run by the Foundation to visitors to our stand: reproductions of individual pages from the Gutenberg Bible, the first book in the western world to be printed with movable type.

The reproductions are produced as in the original, which means that the text is printed, but the initials, any gilding and border decorations are added by hand. At the end of the fair, I plucked up my courage and approached her to ask who the artists were who were working for her and whether she needed anyone else. I really wanted to do it. I had always been fascinated by book illumination and had learned a lot about it theoretically during my studies, but here I saw a unique opportunity to combine my academic curiosity with my personal passion for painting. Since then, I have been one of the artists working for the Shop and I am now also the only one who makes the elaborate pages, which are not simplified but completely designed according to the original, more precisely on the copy of the Gutenberg Bible in Berlin.

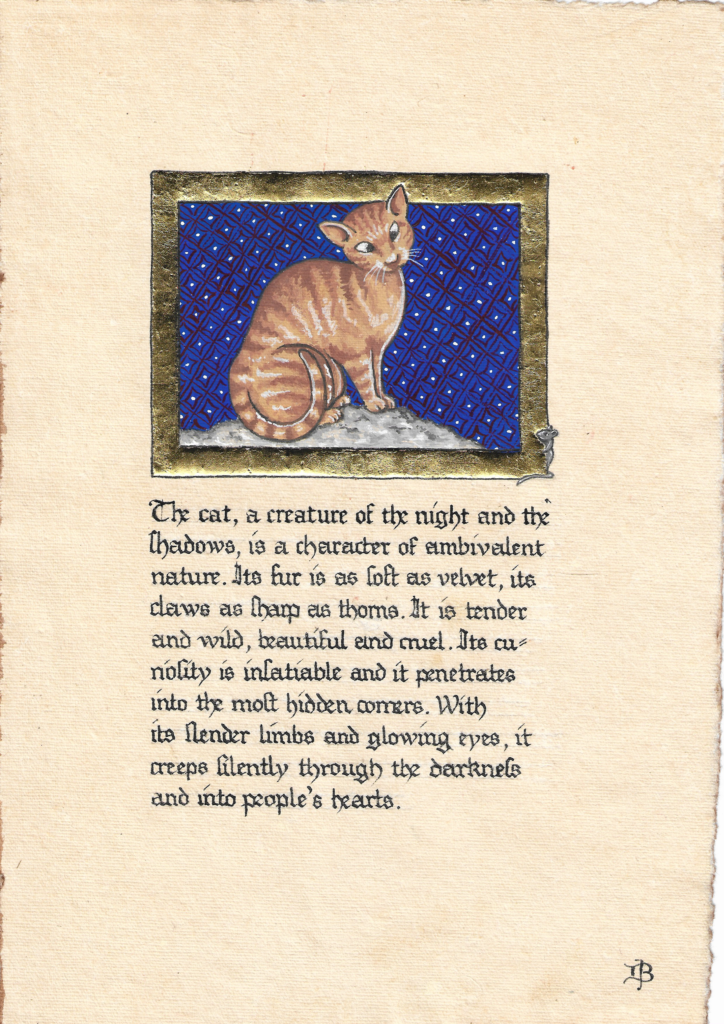

In the years that followed, I gradually acquired more knowledge about this art form of miniature art and taught myself historical gilding by reading sources and trying things out. After I started showing my work on Instagram in 2020 and received more and more questions about commissioning their own pieces, I finally started creating my own artworks in this field. I now mostly paint medieval-looking initials with realistic animal portraits, combining the old style with a new one. Occasionally, however, I also create manuscripts and miniatures entirely in the medieval style.”

Could you provide some historical context for Medieval European miniature art? How did this art form emerge and get transmitted? How did they approach perspective?

“Book illumination in general has a long tradition and dates back to the earliest written tradition. Text and image have always gone hand in hand. The history of miniature art in Western Europe can be roughly summarized as follows: In the early Middle Ages, Merovingian and insular book illumination from Ireland and England emerged first. As Christianity monopolized illumination for itself, it was initially created exclusively in monasteries during the Middle Ages. This was followed by the Carolingian period, which had its origins in the Frankish Empire and was dominated by it from the end of the 8th to the late 9th century. In contrast to the preceding Merovingian book illumination, which was primarily monastic in character, it was also associated with the courts. It then merged into Ottonian illumination. The Ottonians traveled from place to place with their court and thus promoted the production of manuscripts in the monasteries of the empire.

As the power and wealth of the church grew, so did the monastery scriptoria, and the characteristic book of the following Romanesque period is the large illuminated Bible. Stylistically, the period from the 11th century onwards was characterized by Roman and Byzantine influences. The Romanesque period was also the first era in which the regional schools of painting united to form a European style. In the next period of Gothic book illumination, France took on a leading role. From the end of the 12th century, the formal language of miniature art changed again in France and England. At the same time, book production also changed, as more and more commercial writing workshops emerged in connection with the numerous newly founded universities and the monasteries were pushed back as the sole producers of books. In the course of the 15th century, book illumination finally lost more and more of its importance until its time came to an end. The invention of printing with movable type led to the emergence of new technical processes for illustration (If you want to be precise, a distinction is made between printed pictures in books, the illustrations, and painted pictures in books, the illuminations).

The innovations of this last period also lead directly to the question of perspective: Medieval artists were not yet familiar with the theoretical concept of perspective. They often pursued very specific intentions with their depictions, which led to results that sometimes seem downright bizarre to our modern eye, especially with regard to depictions of animals and people. At that time, symbolism was more important to them than aesthetics. They were not at all interested in a primarily realistic depiction, but in telling stories. Medieval artists did not want to draw lifelike figures, but used them to convey feelings, stories and information. Anatomy, perspective and facial expressions were therefore secondary to symbolism; it was more important that they were understood. This only changed in the Renaissance with the new focus on realistic representation. With the discovery of scientific perspective, or linear perspective, in Renaissance art, it departed from the Gothic style. Filippo Brunelleschi elaborated on it and finally gave artists the help they needed to properly depict three-dimensional shapes and figures on a two-dimensional medium. So it was not until the very end of its time that perspective found its way into book illumination in Western Europe.”

How do different miniature traditions within Europe diverge from one another?

“The different eras and miniature traditions in Western Europe are distinguished primarily by style. At the very beginning, so-called insular illumination went its own way: Irish illumination is dominated by complex abstract patterns with many loops and interlacing systems and characteristic animal initials. The artists of subsequent Carolingian book illumination were strongly oriented towards courtly taste and preferred the use of gold. The early Ottonian manuscripts are still clearly in the Carolingian tradition, but now followed a completely stylized formal language. Romanesque book illumination, on the other hand, is characterized by large figurative initials, firm outlines and ornamental symmetry.

This was followed by soft, curved figures with flowing robes in Gothic book illumination, joined by naturalistic flora and fauna as well as contemporary architectural elements and fantasy figures. Finally, with the Renaissance, there were increasingly realistic and spatial depictions in the last phase of book illumination. However, these are now only very rough summaries of various styles. In any case, it is noticeable that the countries alternated in the leading roles, that the current rulers had an influence and that there were reciprocal influences with other art forms. This does not mean that the epoch named after a ruler ended with that person; Ottonian book illumination, for example, extended stylistically beyond the reign of the last Ottonian emperor, Henry II, until the end of the 11th century. Nor does this mean that every stylistic epoch prevailed in every country at the same time. In Germany, for example, Romanesque forms remained predominant until around 1300. Nevertheless, there are clear differences and developments as well as influences in the formal language of the individual miniature traditions.”

The manuscripts often feature humorous or surprising figures, such as grotesque creatures and imaginary scenes. What purposes did these elements serve?

“That depends on the context. Figures, especially animals and creatures that look strange to our modern eye, often serve a very specific purpose, primarily a symbolic representation. As explained in the question above regarding perspective, things like a realistic depiction were usually secondary to the intended message of the miniature. Animals in particular were used to allegorically depict Christian virtues and sins. The paintings were intended to hold up a mirror to people. Strange scenes such as frogs coming out of people’s mouths then stand for a clear and immediately understandable message for the medieval viewer: false prophets.

Of course, it also happens that bizarre figures or scenes have a purely decorative character. Especially when they are so-called drolleries, medieval caricatures, in marginal borders that have no connection to the content of the text. Medieval illuminators liked to use faecal humor or sexual innuendo – so they were by no means prudish or humorless.”

What potential does miniature art hold today? How can this tradition be adapted to the modern world in the digital age and integrated with contemporary art?

“The fact that medieval art still fascinates people today is proven by the numerous images that can be found time and again on social media, for example. Precisely because it sometimes deviates so much from our viewing habits and is so creative, it continues to be very popular – just think of the many funny rabbit illuminations. I therefore think that there are many ways to continue this tradition: by recognizing how timeless some depictions can be and how they can be interpreted in a contemporary way, by playing with the styles and interpreting them with modern means, by learning from their symbolism and thus finding new ways of expressing modern art.

Art is never created in isolation from influences. The mere fact that we or artists today can stumble across and see medieval miniatures so often and on so many occasions means that they live on in modern art.”