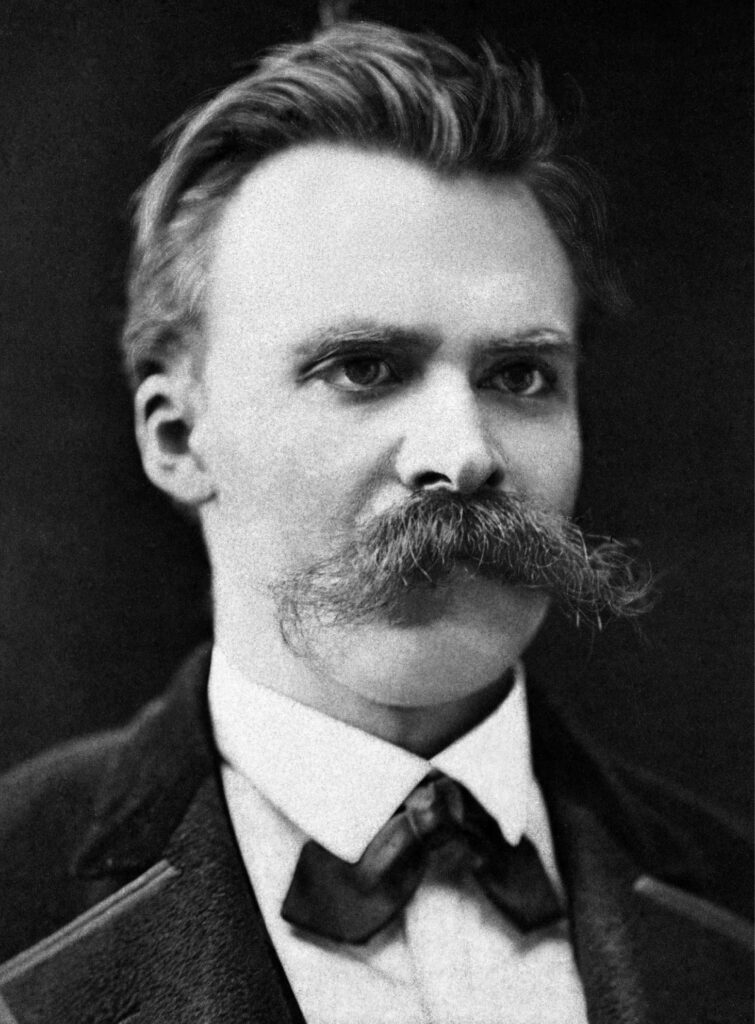

Nietzsche represents an important turning point in the history of philosophy. He has become a popular figure thanks to his aphorisms, which we encounter everywhere nowadays. Having influenced many currents of thought during and after his era, Nietzsche continues to be one of the fundamental references for Revolutionary Conservatism. We discussed precisely this influence of Nietzsche with Carlo Gentili of the University of Bologna.

Nietzsche is known primarily through certain aphorisms that have become clichés. Setting aside these superficial readings, on what fundamental axes should we truly understand his philosophy?

The interpretation of Nietzsche’s philosophy has gone through different periods and subjects. The first to receive his thought were musicians (R. Strauss, Mahler), novelists (D’Annunzio, Th. Mann), poets (S. George), and painters (the expressionist group “Die Brücke”). It was only starting from the 1930s, with the great interpretations of Jaspers, Löwith, and Heidegger, that Nietzsche began to be considered a philosopher in every respect. This happened, however, with prevailing reference to the work that he had, in fact, never written: Der Wille zur Macht (The Will to Power). From the 1960s onwards, thanks especially to the French thinkers (Granier, Deleuze, Foucault, etc.), Nietzsche began to be interpreted above all as a “moral” philosopher—in the sense, obviously, of a critic of morality. This was contributed to by the definitions he often gave of himself, such as “immoralist” and “destroyer of morality.” In reality, such destruction had its roots in a new conception of knowledge that Nietzsche defined, albeit very sparingly, with the term “perspectivism.” This new conception is, in fact, the radicalization of the recognition of the phenomenal nature of knowledge carried out by Kant. In the Preface to the second edition (1886) of Human, All Too Human (1878), Nietzsche observes: «You had to learn to grasp what belongs to the perspective in every judgment of value: the displacement, the distortion, and the apparent teleology of horizons and everything else that belongs to the perspective.» Admitting, by this, that the relativity of moral values originates in the limitation of the cognitive horizon. This relationship between morality and knowledge is perfectly expressed in § 108 of Beyond Good and Evil: «There are no moral phenomena at all, but only a moral interpretation of phenomena.» This Nietzsche, as a philosopher of knowledge and heir to a radicalized Kant, can be said to represent the most vital, and also the most studied, aspect of Nietzschean philosophy today.

The Nietzschean concepts of “death of God” and “nihilism” refer to which rupture in the history of Western thought?

The “death of God” did not enter the philosophical debate with Nietzsche; it has an important history behind it. It is already present in some of Luther’s theological writings, where it is understood as the death of the God incarnated in the person of Christ. It is, however, with Hegel that this idea assumes full philosophical citizenship. Hegel cites it in Faith and Knowledge (1802) and in the Phenomenology of Spirit (1807). Not even nihilism, at least regarding the term itself, is an invention of Nietzsche. It appears in a philosophical context with Friedrich Jacobi’s letter to Fichte (1799) in which he reproaches idealistic philosophy for having dissolved the sensible evidence of faith in God into concept and, for this reason, he defines idealism as a whole, “contemptuously,” as nihilism. Subsequently, it was Karl Ferdinand Gutzkow, with his story Die Nihilisten (1854), who gave the term a literary and political meaning, giving voice to the bourgeoisie disappointed by the Revolution of 1848. Turgenev was inspired by him in his novel Fathers and Sons (1862). Both Gutzkow and Turgenev were well known to Nietzsche. For Nietzsche, however, and to summarize to the extreme, nihilism is the form of the historical unfolding of Christianity which, being essentially a moral philosophy, could not sustain the “lie” of the existence of God for too long. In the posthumous work European Nihilism (1887), Nietzsche nevertheless credits Christianity with saving man from the “first” nihilism, i.e., from the discovery of the futility and senselessness of life. But, having successfully completed its primary task, Christianity is destined to turn the nature of nothingness against itself.

In what way did the critique of nihilism and the call to create new values inspire the thought of the “Conservative Revolution” in the early 20th century?

The Conservative Revolution was born, as a label and historiographical category, only in 1950 thanks to the dissertation discussed by Armin Mohler under the guidance, among others, of Karl Jaspers. It was not, in reality, a unified political-cultural movement. With this term, Mohler unified a series of national-conservative tendencies and authors, even those distant from each other. The most prestigious figures often indicated as exponents, from Oswald Spengler to Ernst and Georg Friedrich Jünger, were in reality, rather, supporters or sympathizers. Perhaps the most significant work produced by this movement can be considered Das dritte Reich (The Third Reich, 1923) by Arthur Moeller van der Bruck. A constant in the works of this author is the search for a continuity with tradition to be achieved through art and the concept of style. It is here that a sign of Nietzsche’s presence can be found. The Drittes Reich he speaks of has nothing to do with the future National Socialist state, but is a reference to the prophecy of the Italian mystic Joachim of Fiore, which had found wide following in Germany and had undergone an Enlightenment interpretation in Lessing’s The Education of the Human Race (1777-1780).

How should one evaluate Armin Mohler’s interpretation which defines Nietzsche as the “prophet of the conservative revolution”? To what extent does this definition coincide with Nietzsche’s true thought and to what extent does it go beyond it as a posthumous reading?

Beyond the aspirations of the conservative revolutionaries, often characterized by syncretistic amateurism, an expression of authenticity was certainly the definition of a cultural horizon that can be identified in the distinction between Kultur and Zivilisation. Nietzsche was undoubtedly its inspirer, rather than its prophet, and it found a well-known interpretation in Thomas Mann’s Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man (1918). On the other hand, if it is true, as already mentioned, that the label of Konservative Revolution is only posthumous, this formula had already been used by Hugo von Hofmannsthal in the speech given at the University of Munich in 1927: «The process I am talking about is nothing other than a conservative revolution of unprecedented scope in European history. Its goal is form, a new German reality, in which the whole nation can participate.» And it should be remembered that in The Magic Mountain (1924) Thomas Mann had defined the character of Leo Naphta as «a revolutionary of conservatism.» In the indication of these cultural horizons, the legacy of Nietzsche is undoubtedly very much alive.