While I was doing research on folk Muslim ephemera, I came across Tatar Shamails. The colourful designs and the themes used attracted my attention. I couldn’t find anything about them in Turkish, but I was happy to see traces of us while researching these shamail, which are part of both the religious and national culture of the Tatars. We had a short interview with Shamsutov Rustem Ilshatovich on Tatar shamail. It is a very important endeavour for an artist who is devoted to preserving his own identity to try to do so through schema.

Could you briefly introduce yourself?

I am Shamsutov Rustem Ilshatovich, born in Kazan, Tatarstan, author of Tatar Shamail and Word and Image: From the Past to the Present. I am an art historian and an artist. It is probably incomprehensible to Turkish readers why, after studying as an architect in Moscow, I suddenly entered Kazan University in the 90s and started to study Tatar language and schemata.

Kazan Tatars have a problem of losing their mother tongue. I think this is a general problem of globalisation. As a result of the double alphabet change in the 30s of the last century, the Tatars began to lose their identity.

Language and religion, spiritual foundations – these were lost in Soviet times. My education was in the late 80s and early 90s – perestroika, the time to rethink spiritual and historical values, to return to my roots. Shamail combined these values – language, spirituality and religious foundations. For Tatars, the Arabic alphabet and the shamail are a symbol of these foundations.

Unexpectedly, I immersed myself in this subject very seriously. Simultaneously with studying the Tatar language and the Arabic alphabet at Kazan University, I started working at the Galimjan Ibragimov Institute of Language, Literature and Art of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Tatarstan. Studying the Tatar language and the Arabic alphabet gave me a foundation, a support point. This is very important for an artist.

What is a Tatar shamail?

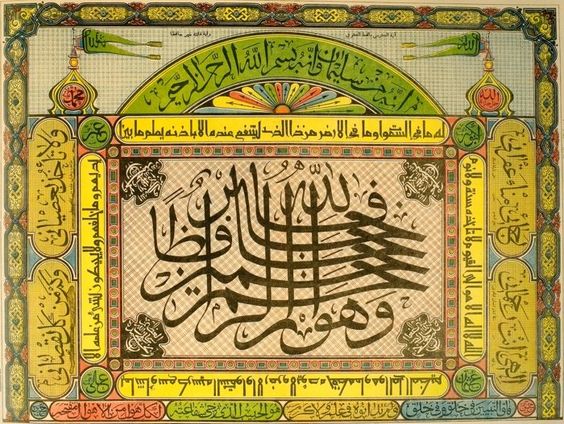

Shamail is a sacred painting with religious content. There are two types of shamail: made on glass and illuminated with foil. In Turkey, such works are known as ‘under glass’. Another one is the printed ones made by typographic method.

It is believed that the first shamail on glass appeared in Kazan at the end of the 19th century as Turkish imports. Subsequently, shamail under glass became popularised in the countryside with the works produced by folk artisans. The ‘shamail’ switches to prints. Printed shamail became widespread with the development of the printing press in Kazan Tatars in the early 20th century. Hajj testimonies are the source of many illustrations in printed shamail.

What themes are usually used? They have very different and contrasting compositions. I have also seen mosques in Istanbul in some examples.

If we talk about the under-glass shamail, they mostly depict Qur’anic surahs popular among Tatars, among them the Ayat al-Qursi. The prints can be called the Muslim encyclopaedia of their time. They covered all aspects of the life of a pious person, from pictures of architectural monuments, including numerous Turkish mosques, to symbols of various Sufi schools.

The widespread distribution and popularity of printed shamail was also linked to the enlightenment and reform movement in Islam. Often, printed images of shamail were accompanied by extensive explanatory texts in Tatar.

We can say that shamail represent both religious and national identity.

Of course. Shamail on glass are kept in many families. At the same time, many people no longer know the Arabic alphabet. Today, globalisation has also affected religion. Whereas a century ago shamail were made by folk craftsmen, today the authors of shamail are a few professional artists. The problem of preserving the mother tongue remains serious. Time will tell whether this art will be in demand tomorrow.

Apart from the Tatars, are there other examples in the Caucasus?

Printed shamail in the Caucasus appeared later under the influence of Kazan publications. The Tatar shamail under glass and the prints are technically and content identical.

Are Tatar shamail made today?

In the 90s of the last century shamail on glass was revived in the work of some professional Tatar artists. In general, the modern direction of Islamic art has significantly expanded its boundaries, both in terms of content and technique of execution. The ‘sacredness’ of these works has disappeared and today they are more reminiscent of modern Arabic graphic art.