We had a great introductory interview with Franco Milanesi on political philosophy, history, and especially the ideas of Ernst Niekisch. We touched on many topics, including how Niekisch combined the concepts of conservative revolutionism and national Bolshevism, and his relationship with Ernst Jünger.

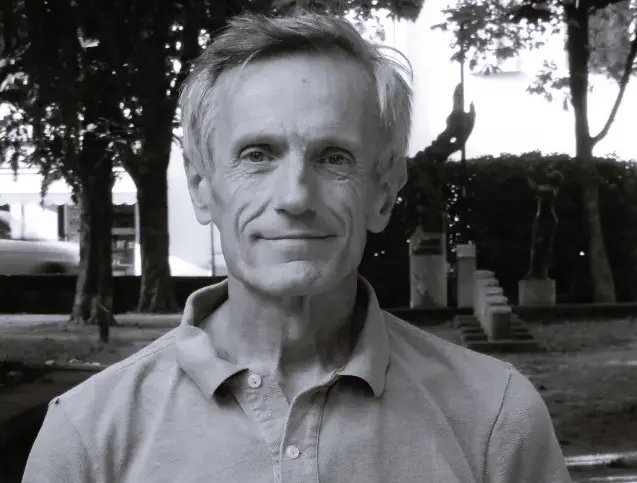

Can you briefly introduce yourself?

I was born in Turin on July 5, 1956, and graduated from the University of Turin with a thesis on dissent within the Italian Communist Party (Pcd’I). I taught in Pinerolo and obtained my PhD from the University of Turin in 2010, earning a second PhD from the University of Genoa in 2014. I publish articles in various journals. In 2008, I published Dietro la lavagna (“Behind the Blackboard”), based on my school experience, and in 2010, Militanti (“Militants”) was released by Punto Rosso. In 2011, I published Ribelli e borghesi. Nazionalbolscevismo e rivoluzione conservatrice (“Rebels and Bourgeois: National Bolshevism and Conservative Revolution”) with Aracne, and subsequently Nel Novecento (“In the Twentieth Century”) with Mimesis, a work dedicated to the political journey of Mario Tronti. In 2022, Il tempo inquieto. Per un uso politico della temporalità (“The Restless Time: For a Political Use of Temporality”) was published with Ombre Corte. I wrote the preface for Il regno dei demoni. Una fatalità tedesca (“The Kingdom of Demons: A German Fate”) by Ernst Niekisch in 2018 for NovaEuropa. I participate as a speaker at conferences and public meetings in various Italian cities. I was the secretary of the Communist Refoundation Party at the Pinerolo circle and also held administrative roles in the same city.

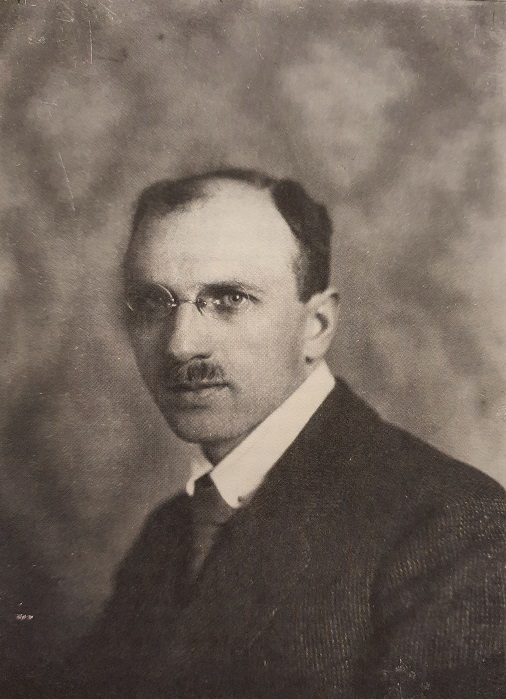

Ernst Niekisch occupies a unique position within the Conservative Revolution as a national Bolshevik. What are Niekisch’s basic ideas? How was he able to combine being both a conservative revolutionary and a national Bolshevik?

Niekisch’s political philosophy is closely intertwined with his political anthropology. The bourgeois Gestalt (form) is indeed the theoretical focus of his works. This figure imposed itself in modernity and is what upholds capitalist dynamics. The critique of capital becomes a critique of the “type of man” who embodies and disseminates it. The bourgeois unites two characteristics: proprietorial individualism and universalism. Against the first, Niekisch asserts the communitarian and socialist demand. The individual finds their own “meaning” only within the social community—a community of equals where the State represents the concrete institution that realizes and promotes socialism. However, this society needs an identity, and the national element serves this function. This is the dual root: nationalist (anti-universalist) and Bolshevik (anti-capitalist). The Conservative Revolution is based on similar premises: revolution against capital and the bourgeois human form; preservation and reactivation of national tradition and the communal roots of humanity.

Can you explain the bourgeois human form they oppose?

The bourgeois form (Gestalt) is a way of human existence that we can consider abstractly—as a form. The bourgeois places personal security, decorum, money, family, and the individual at the center of their existence. All this opposes those equally universal characteristics embodied by the Prussian spirit: sacrifice, military spirit, sense of community. For Niekisch, the proletarian who emerged in the Soviet world, the homo sovieticus, embodies some of these characteristics—the same ones present not only among Prussians but also among Slavs.

What was Niekisch’s stance towards the National Socialists? In what ways did he clash with Nazi ideology, and how did this clash affect his political life?

The clash with Nazism was extremely harsh. Niekisch had already spent two years in prison after the experience of the Bavarian Soviet Republic. Initially, he expressed interest in the Strasser brothers’ experience, but by 1932 he published one of his most significant works, Hitler, ein deutsches Verhängnis (“Hitler, a German Fate”), a historical-theoretical text in which he attacked National Socialism as an expression of the southern, bourgeois, Catholic spirit. The victory of Nazism would lead to the full Latinization of the German spirit and the introduction of the mercantile “values” of capitalism. The Nazis launched a violent campaign against the book. In January 1939, Niekisch was sentenced by a special court to life imprisonment, confiscation of all his assets, and deprivation of civil rights. He was liberated, almost completely blind and paralyzed, by the Red Army on April 27, 1945.

What does the “Latinization of the German” mean?

Latinization means yielding to the values of the “South,” particularly those Catholic values that, for Niekisch, are the same as those of mercantile societies dominated by the bourgeois figure.

What kind of geopolitical structure did Ernst Niekisch envision by establishing an alliance between the Soviet Union and Germany? What role did Eurasian concepts play in this structure?

For Niekisch, Eastern Europe is the barrier against the “American” drift of the West. “East” means Bolshevism. As always, he interprets political phenomena from an anthropological perspective as well. Bolshevism brought onto the historical stage a dominant figure: the communist militant. A minority capable of deciding, imposing, and realizing a policy in which the State, the ruling class, and the masses are literally standardized—that is, unified in a single form. The Bolshevik Revolution completes the same Slavic character: essentially collectivist, anti-individualist, military. These are the characteristics that, in an ideal East-West fusion—in other words, the Bolshevization of the West and Germany—could halt the bourgeois and materialistic drift of the West. Niekisch’s reading of history is always imbued with metaphysical and spiritual elements. Hence his critique of Marxism, which, on the contrary, reduces history to an economic and material conflict.

What are the metaphysical and spiritual elements in Niekisch’s interpretation of history? How does he use them?

Sharp oppositions like North/South; Prussian Protestantism/Latin Catholicism; warrior spirits/pacifism; absolute State/free mercantile society; Communism/individualistic Liberalism represent metaphysical crystallizations that have little to do with the complexity of peoples in their concrete existence. In modern historiography, “phases” fixed in rigid chronological schemes are approached with great caution. Niekisch even goes so far as to speak of the “Eternal Jew,” “Eternal Latin,” “Eternal Barbarian,” not as purely abstract models but, in a Hegelian manner, as concrete universals that objectify themselves throughout history. Obviously, not all Latins have those characteristics. But the power of form entirely marks history and its phases.

His friendship with Ernst Jünger is a very interesting detail. How did the two thinkers influence each other? What exchanges of ideas emerged from this intellectual relationship?

They are two “strong” thinkers who developed their ideas starting from different cultural lines and texts. I would summarize some common grounds:

The First World War as a “Saddle Period”: Both viewed the war as a pivotal time for forming a revolutionary “type”—anti-bourgeois and radically mobilized toward changing the state of affairs. The concept of “Total Mobilization” (Die totale Mobilmachung) profoundly influenced Niekisch.

Ernst Jünger, in turn, recognized in Niekisch’s class-based nationalism a strong stimulus and wrote numerous articles in Widerstand. Jünger’s Arbeiter (“The Worker”) is essentially Niekisch’s national proletarian—the “eternal barbarian” who will dominate the Western world in the light of Prussian, spiritual, and popular values.

The two maintained contact from as early as 1927. After that date, Jünger’s stance toward the regime became very cautious; he even served as an officer in Nazi-occupied Paris. Actively involved in the July 1944 assassination attempt on Hitler, Jünger was not prosecuted due to Hitler’s appreciation of his writings on war.

They shared a metaphysical conception of history, based on the succession of epochs and the concept of anthropological-political form or Figur. Jünger said of Niekisch, “He was among the few who immediately understood the meaning I wanted to give to the figure of the Worker. I want to acknowledge this because even very sharp minds like Spengler and Carl Schmitt did not understand me; indeed, they misunderstood my intentions.”

There were differences regarding their attitudes toward the USSR; Jünger always displayed profound hostility toward it.

Do Ernst Niekisch’s thoughts have any followers today? What does he say to today’s world?

There are many “red-brown” currents in various European countries. They arise from the convergence of national issues with anti-capitalist and anti-bourgeois social radicalism. Niekisch’s ideas, though deeply transformed, are disseminated as Eurasianist perspectives (consider his Ostorientierung), as critiques of Americanism and of a Europe unified by market flows.