In recent years, there has been a growing interest in quality fragrance and artisanal niche perfumes in Turkey. Especially valuable and characteristic ingredients such as “oud” have become the focus of the perfume world. J.K. DeLapp is one of the first names that come to mind when it comes to “oud”. In this interview, we talked about both the intricacies of the artisan perfume world and DeLapp’s approach to “oud” under the roof of Rising Phoenix Perfumery.

Could you briefly introduce yourself? How did you step into the world of perfumery?

I am J.K DeLapp. Rising Phoenix officially started back in 2011, while I was still in med school in San Diego, although it was 2014 before we really started launching products.

Many that follow my work know that I work in Chinese medicine. I’m in private practice in Atlanta. I spent some time working in three hospitals in Shanghai. In my earlier years I spent my last year in university in Avignon, and worked in Paris after college. I’ve been fortunate to have traveled extensively.

While in med school we had to memorize quite a bit of information about hundreds and hundreds of medical substances, including the Chinese pinyin, the common English names, and the Latin scientific names. The Latin names started tugging at something in the back of my mind. It didn’t take me long to figure out that pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, cosmetics, fragrance, flavor, and the incense and spice trades were all built on the back of herbs. Herbs I was really diving deep down the rabbit hole on.

In my third year of school, something clicked and I realized, “I could be a physician. Or, I could be a physician, and… !” I wanted to tap into a much larger world that was built on the back of something most never think twice about: herbs. Foundations in a multitude of global modern-day markets.

Since natural oils are distilled or extracted from herbs – what we call essential oils, “absolutes”, etc. – are really pharmaceutical-grade herb extracts, fragrance seemed like a natural place to start. As a kid, I wanted to be an archeologist. Or a spice trader. I worked in film and television before going back to school for medicine. It wasn’t until years later, when I was working as a physician and focusing on what I call my “golden triangle”– the point of intersection of the medicine, cosmetic/fragrance, and incense trades – that I realized I kinda DID become both an archeologist and a spice trader!

Many don’t realize that, historically, it was physicians and pharmacists that made fragrances. Up until about 100 years ago, if you were going to buy perfume, your local pharmacist was likely making what you were wearing. In the more distant past, fragrance (i.e., perfume and incense) were considered medicine first, as well as something that smelled nice.

Who were Johnson & Johnson? Three brothers that sold medical and pharmacy equipment. Who was Dr. Pepper? The inventor, Charles Alderton, was also a pharmacist in the 1880s. Dr. Pepper was also a medical-elixir-turned-popular-beverage. Ever used Listerine? Dr. Lister’s work in England in the 1860s inspired Dr. Lawrence in the US to create a surgical antiseptic based on eucalyptus essential oil, menthol (likely distilled camphor at the time or camphor resin), methyl salicylate (better known as white willow bark, now synthesized and used as an over-the-counter painkiller), and thyme essential oil in an alcohol base.

Realizing that a lot of common household name-brand products of today really started from a place that I, myself, somehow found myself working inspired me to apply my work in medicine to a much broader body of work. Hence the name: Rising Phoenix. Giving new life to old practices.

When designing a fragrance, which notes do you focus on, and how do you shape this process?

Generally speaking, when composing I start with the concept, first. Many of my fragrances are an “encapsulation of time and place”. Mirage, for example – is what I envisioned a vision of refuge in the desert would smell like. Or Bushido – the scent of a Samurai on the eve of battle. The scent of impeding death.

I get these flashes of inspiration, which sometimes lead to doing some reading and further research about the historical and cultural context of the idea, materials that may have been a part of that time or event – and then the composing starts.

I think less about “which notes will I use”, and more about which notes I want to be the focus or emphasis of a composition. From there – it’s about balancing the formulation. Fragrances need to accomplish 3 things: Scent Progression – it must tell a story. Nobody wants a linear fragrance from start to finish. It needs to transition and dance. Longevity – there’s an expectation that fragrances will last X amount of time. With natural fragrances – 4 hours is usually considered a great success. I aim for 8-12 hours of performance. And most importantly, it’s gotta smell nice. It should be a compelling scent. Something that should draw you in, and align with the vision of the concept.

How do artisanal (handmade) perfumes differ from industrial production? What are the advantages and disadvantages of this approach?

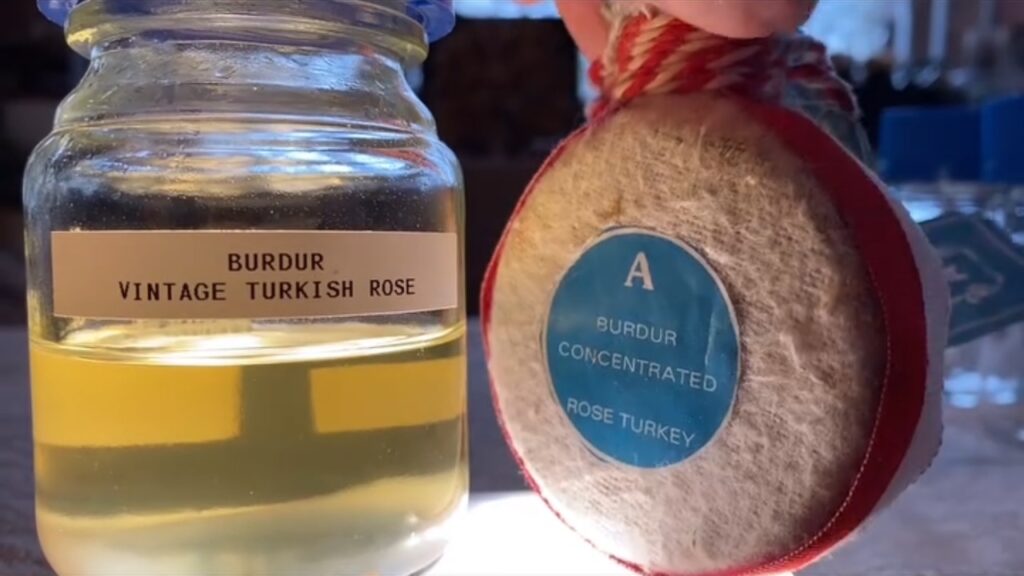

A big part of this – is that we do it all by hand, and that means different things for different people. At Rising Phoenix, I actually try to create in-house as many key components that I use in my fragrances as possible. I have several distillation operations in SouthEast Asia where we produce many of the materials used in my products. If I can’t produce it – I’ll move to commission a batch with a fellow artisan. If that can’t be done, I’ll go to another colleague or smaller firm before reaching out to one of the big producers we all think of when we think of fragrance. So I try to in-house as much of the material production as much as possible.

Batches are smaller. All bottles are hand-labeled and hand-poured by yours truly. It’s me doing the compounding and composing and fulfillment of orders. I have my teams of guys overseas doing most of the material production, which I also do some of. But it’s me hand-cutting woods and doing some of the extractions, the compounding, the fulfilling.

All in all – its me doing the bulk of the work and all of the selling and fulfillment. It’s a LOT of work. Contrast that against machine filling and mass production and conventional distribution – which is practically everything these days. From cars to grocery, clothing to electronics. Very little, if anything, you purchase these days is made by hand, let alone by a small company.

Artisan products maintain Soul. Sadly, most are more than willing to trade that Soul for a cheap price tag. The prices artisans charge don’t fall into our pockets. The vast majority of the cost is simply what it takes to run a business. It’s a tough way to make a living. I’ll be honest … it’s a little funny to hear people yell about paying workers living wages, and then turn around and demand us artisans work for free and live on slave wages, ship immediately, and be available 24/7. Artisan. Not Amazon.

Oud, often associated with the Middle East and Arab culture, plays a significant role in your work. As an American, how did your interest in oud develop?

Well – Oud, the Oil, yes. Agarwood, the wood – has it’s roots in the Far East. I was familiar with Agarwood first as an incense material. Primarily from Japanese and Indian incense.

When I first started looking for Sandalwood and Agarwood – it was for materials to make incense. Later on it dawned on me that the materials were also being distilled to produce oils, and that essential oils were essentially pharmaceutical grade extracts of herbs. Both the Oils and the Woods were used in Medicine – both in the Near and Far East – as well as in the West. Learning about their use in the Middle East was all apart of learning about the history and movement and use of the materials.

It’s a bit like the culinary arts. We all cook and eat food. The materials used and how we cook and put them together is the fun part of the cultural exploration.

How is oud obtained? What are the key differences between various types of oud? How can one distinguish a high-quality oud? Additionally, how can consumers differentiate between synthetic and natural oud?

How Oud is obtained : Simply put – like any material – it is distilled. In this case, from infected wood. We are essentially distilling the immune system of an Aquilaria or Gyrinops tree. The HOW of distillation is in part how we get different odor profiles. Oud I think is actually best discussed as an analogue to Wine, Tea, and Whiskey.

With Wine and Tea – the Terroir and the Production Methods are of primary impact. With Whiskey – the production and barreling, casking, and aging play a big role. All of these aspects of Terroir and Production Method and Aging play the biggest roles in how an Oud Oil smells.

What is the Species? What is the Terroir? What part of the infection and what quality of wood is being used? Soak, Fermentation, or No Fermentation? How is it Distilled, at what Temps, in what kinds of equipment, for how long, etc? Is it then aged? And if so – how was it aged?

How can one distinguish a high from low quality Oud?

Again – Wine, Tea, and Whiskey are great examples. And it comes with experience. Like the above – we all know a good glass when you have something exceptional, but the enjoyment is really in the nuance – and appreciating the nuance comes with training your nose on known samples of quality.

Just like Wine or Tea or Whiskey – the market is awash with mass produced junk that is manipulated, flavored, colored, and who knows what else to get it cheap and passable and replicable. I can’t speak for Europe – but here in the US, something like less than 5% of wine is an actually vineyard production. Tea in Asia – and by “Asia” I primarily mean China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Japan – for those that know what I’m talking about, Tea there and “tea” over here are entirely different beasts.

Most Whiskey sold over here blended, flavored, modified. Very little of it is single cask, small production, highly unique and nuanced. Artisan products of any kind are challenging to mass market. And the higher the price tag goes – the more challenging it gets. And real Oud ain’t cheap.

As to differentiating between natural and synthetic specimens – shopping with someone like Rising Phoenix is your best bet. Like I’ve discussed about everything else – the majority of what is on the market is tortured and approximated in to something that is “oud-like”, or “oud’ish”. Rarely will you find pure, unadulterated Oud oils out on the mass market, just as you wont find real hamburgers in a fast food joint, or hand-made and hand-tailored clothing in a department store, or single barrel specialty cask-aged whisky at your corner convenience store. You’ll have to go to a specialty boutique or an artisan vendor like myself to find the real deal. It just so happens I have THE widest selection of pure Oud oils available anywhere in the world, and they are available at the touch of a finger on the internet in our online shop.

Beyond its traditional use, how do you see oud’s place in modern perfumery? What kind of “scent profile” do you aim to create when working with oud, and what emotions does it evoke in the contemporary world? What feedback have you received on this?

Good questions. The majority of the “oud” in perfumery is really an Accord – a composition of multiple materials, often synthetic, that approximate an “oud-like” scent.

The real stuff will more likely be found in artisan and smaller company products, where the cost is less prohibitive, and the customer knows the price they are paying is for a higher percentage of real materials, and superior examples of them, at that.

Oud, itself, is a vast spectrum of potential odor profiles, and for that reason it is a very compelling material to work with. Due to the difficulty in continuity of scent from one batch to the next, it is ideal in smaller productions, and best formulated to showcase the Oud as one of the surfaces of the olefactory gem.

With that said – there are ways of making batch material more consistent for larger scale application. As to the goal of the scent profile – that depends a bit on the concept. The”right” odor profile will differ from fragrance to fragrance depending on the goal. Something more strong and horsey for one, maybe something pristine and green for another. Fruity yet for a third, and hay and leather for a fourth. Just depends on what is being made. It’s a bit like asking what the right color for a painting is? The right color is what’s right, in that moment, for that specific goal. It may change in the next painting.

Emotions … Well, that really depends largely on the cultural context of the wearer. What to one may smell familiar and warm may to another smell abhorrent and repulsive. I imagine in the right hands, Oud should never evoke horror in a composition – but have you ever smelled Civet up close and personal, straight up and the real thing? Yet in a composition – it is a thing of beauty, this scent of derrier from the backend of an animal. A spoonful of vinegar in your mouth might elicit a gag, but in a dish … the zing is delightful!

Pure Ouds worn straight up for what they are, on the other hand – I think here you find superb specimens that wear as if they were perfumes in and of themsleves. Florals, Fruits, Woods, Resins. Green, Smokey, Purple, Red. Clean or Manure. Bright and Airy or Dark and Peaty. I have smelled hundreds and hundreds of unique Oud oils, if not more – and I continue to be surprised by the near endless potential of this singular material that is anything but singular. Limitless is the possibility when it comes to the majesty of Oud.