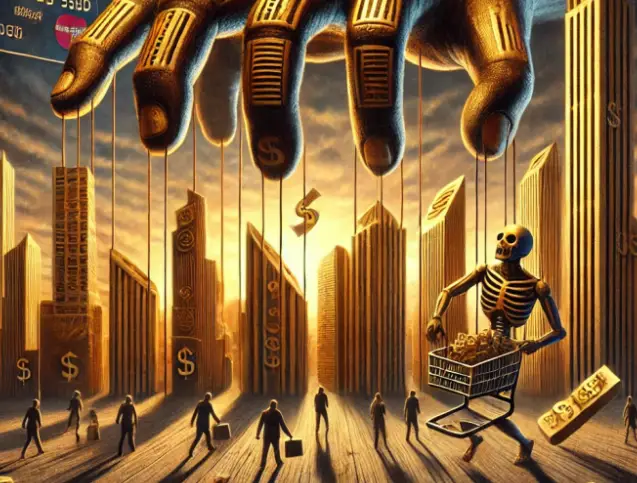

We owe to Ezra Pound his coinage of the word ‘usurocracy’ from the Latin usura and –cracy, which latter is from the Greek –kratia ‘power, rule’. Democracy is the rule of the dêmos – the people, and usurocracy is the rule of usury. Note that there is no agent empowered here but a process. That process elevates some and demotes others, and it does so continually, and thus produces chaos. Usury rules. Chaos rules.

In what follows we have finally to put behind us the antiquated notion that somehow our money is OK, but that what matters are the interest charges made for loans and other things. Those interest charges were simply a step towards the real goal: the creation of money from nothing. In its early stages this was called ‘fractional reserve banking’. Accepting the jeweller’s acting as a manager of funds who issued receipts for the gold and silver deposited with him, meant that from the very first day, he was enabled to write receipts for funds he didn’t have and thus fiat money was born.

Although usury dates back to the very first city-states in Sumer and Babylon, the current usurious order derives from a fateful marriage between Judaism and Christianity, whose adherents detest each other but which have formed a symbiosis, their mutual loathing being the weak link.

In a verse in the Bible Jews were forbidden to take usury “from thy brother” but were licensed by additional words, which in all probability they falsified, to take “from the other”. “The other” were the enemy and usury was a weapon to fight them. When unleashed in a civil setting, however, it spreads far beyond the two contracting parties and creates the society of dog-eat-dog, in Professor Benjamin Nelson’s inimitable book-title it transformed tribal brotherhood into universal otherhood. It is the very source of the nihilism and alienation of modern life in the West.

The Christians, on the other hand, resorted to their strongest suit: hypocrisy; they hated the usurer but borrowed from him in any case. Thus for Catholics usury was a mortal sin, but the interest rates could be 250% and more. The Catholic banker went ahead sinning, mortally, but salved his conscience by funding the Renaissance, whereas Catholic theology required him to desist and make restitution of his ill-gotten gains. But why would he do that when the Vatican account was the most prized possession for a banker?

The Protestants wanted to do away with it entirely, but made the fatal mistake of the half-measure by trying to limit the interest rates. Thus Calvin said 4% could in certain circumstances be acceptable, but then Henry VIII said 10% and it continued to rise over the centuries until payday loan sharks could charge 1,000% and more without blushing and with no fear of legal consequence.

However, there is an intrinsic trap in usurocracy as a title because it suggests that someone or something is ruling or in charge, which might be a comforting thought even if the person were to be unworthy, for at least there is someone deciding, and suggests that then if we remove them, we can perhaps plot a better course. But what if there is no one in charge, no one with a plan, conspiratorial or otherwise? And how can we make sense of such a time, let alone chart a course in it?

First of all, the ordinarily honourable course of overthrowing an unbearable tyranny, of mounting a revolution is perhaps no longer possible at all, because if no one is authentically in charge, you can’t overthrow them. You can’t overthrow usurers, because they are not in charge either.

What you can do is withdraw from usury, individually, as families, as businesses and as nations. This is called ‘forgoing riba’. Allah commands: “You who believe! have taqwa of Allah and forgo any remaining riba if you are believers.” Remember that the crime of usury applies to those who lend usuriously, those who borrow, those who record it, such as lawyers and accountants, and those who act as witnesses to the transaction, and in one sense we are all witnesses to this crime.

The Christian mistake was that they deplored charging interest on a loan, but took no account of the other parties to the transaction without which it could not happen. Thus they came to hate the Jews who lent them the money, but did not consider that they had any responsibility for borrowing from them. This was a part of the origins of Western anti-semitism. Some Muslims have inherited the same attitude: they see no harm in borrowing from banks but would not themselves consider lending at interest.

What to do? This question we ask too soon. The Prophet, may Allah bless him and grant him peace, is reported to have said: “Whoever of you sees something repugnant ought to change it with his hand, and if not possible then with his tongue, and if not possible then with his heart, and that is the weakest of īmān.” The reality is that we have to start not at the beginning but with the end of the hadith.

The heart, being the seat of feeling and emotion, naturally finds repugnant those things that Allah has forbidden, murder and theft, and, of course, usury. Islam is the dīn of natural pattern (fiṭrah), and we naturally hate vice and love virtue. And this sense of repugnance for usury was common to Jews, Christians and Muslims.

So what changed? First, the Reformation and the grudging Protestant acceptance of a kind of limited usury. However, it is the later development of ‘science’ that sets in stone an entirely different attitude not only to usury, but tellingly to moral issues such as fornication, adultery and sodomy.

After Newton had articulated his laws of mechanics with such success, what had been implicitly slipped under the radar was the mistaken understanding that the universe and man are machine-like and operate according to mathematical and physical laws. All the sciences laboured to emulate Newton’s success, not the least of them economics. Thus, just as the act of adultery was relativised and marriage to all intents and purposes began to disappear – until today in popular Western culture it is assumed that a man and a woman will sleep with each other before marrying and that in fact there may be no reason to marry at all – so usury was incorporated into the mathematisation of economics, its definitions altered so much as to become meaningless. Redefined as ‘extortionate’ interest rather than plain interest, where do you draw the line? One man’s moderate rate is another’s extortionate. No one knows any longer, and the very idea has been abandoned. And the issue of the creation of the currency entirely overlooked until it was finally put back on our screens again quite recently.

This is a consequence of forsaking the heart’s natural love of what is good and its loathing for what is bad, and the heart’s replacement with intellect defined as sets of rational propositions bound together by reason and logic, except that it is clear you can achieve whatever purpose you want by such processes.

One should not skip over that word ‘love’ lightly. It is perhaps one of the most common words in the Book and the Sunnah, and it is clear that it means what it says, that the issue of Islam revolves around love, love for Allah and His Messenger, peace be upon him, the love that men have for each other, particularly when engaged together in a noble struggle, the sisterly love of women for each other, the love of men and women for each other, and the love of family, parents, children, brothers and sisters and so on.

This love is naturally counterbalanced by genuine hatred for what is wrong, such as the massacres we have seen perpetrated on the Muslim people, and most particularly in the recent times on the people of Gaza, the misappropriation, meaning theft, of their lands and properties, and so on. Injustice and its perpetrators are hateful. One should love with the love of Allah and hate with His hatred.

As well as its emotion and feeling, which naturally repudiate what is repugnant, the heart is the faculty of ‘aql that sees. Allah says:

أَفَلَمْ يَسِيرُوا۟ فِى ٱلْأَرْضِ فَتَكُونَ لَهُمْ قُلُوبٌۭ يَعْقِلُونَ بِهَآ أَوْ ءَاذَانٌۭ يَسْمَعُونَ بِهَا ۖ

فَإِنَّهَا لَا تَعْمَى ٱلْأَبْصَٰرُ وَلَٰكِن تَعْمَى ٱلْقُلُوبُ ٱلَّتِى فِى ٱلصُّدُورِ

Have they not travelled about the earth and do they not have hearts to understand with or ears to hear with? It is not eyes that are blind but hearts in breasts that are blind.”(Sūrat al-Hajj 22:46)

This astonishing āyat proceeds in two steps, first asserting that what the heart does is ‘aql an activity, not a thing; second, the failure to do that is blindness. The ‘aql isn’t ratiocination but ‘seeing’.

We have to learn to see again. We have been affected by the kufr of the age. Allah says about the group who say that they believe whereas they do not, that which means: “And over their hearts there is a covering.” Thus the prime function of ‘aql which resides in the heart, to see, is taken away. All that is left are the rational processes of what people call the intellect, which, however, may construct elaborate edifices in order to achieve an ‘Islamic state’, ‘Islamic finance’ and ‘Islamic banking’, which are all problematic and, as yet, not thoroughly examined or understood concepts.

However, when the seeing of the ‘aql is backed up by reason, rational processes and the sciences of the sharī‘ah, then the result is irrefutable except by those deniers determined to do so.

Once one sees with the eye of the ‘aql that is in the heart, reinforced by our rational and shar‘i sciences, then one may move on to the second part of the hadith and speak. If such a one speaks, it will have some weight. That is who we are called to be, for Allah, exalted is He, says that which means: “Let there be an umma of you who call to the good, command the right and forbid the wrong.” Some understand that “of you”, which in Arabic is minkum, to mean that there needs to be a group among the Muslims, whom He, exalted is He, calls an umma, who undertake this task. Others have understood it to mean that as an umma we ought to be such people.

So this is the threefold task of speech: calling to the good or to the best, commanding what is right and forbidding what is wrong. Since Allah, exalted is He, does not qualify the object of this speech, there is no basis for considering it something restricted to Muslims speaking together among themselves. This is how we have to be among mankind and among ourselves.

Contrary to the French Revolutionary values that have entered our community, this speaking is not strident and denunciatory, the famed and much abused ‘speaking truth to power’, but is done with adab and wisdom. Allah says: “Call to the way of your Lord with wisdom and fair admonition, and argue with them in the kindest way.” Indeed, He, exalted is He, says to the Prophet, peace be upon him: “Say: ‘This is my way. I call to Allah with inner sight, I and all who follow me.”

This is particularly important when addressing those in authority, the -ocracy. Allah, exalted is He, commanded Mūsā and Hārūn, peace be upon them, to: “… speak to [Fir’awn] with gentle words so that hopefully he will pay heed or show some fear.” Clearly the worst of tyrants, let alone authoritarian Muslim rulers, is not as bad as Fir‘awn who told people “I am your Rabb Most High!.” Equally no one who undertakes the task of commanding the right and forbidding the wrong will ever rise to the noble ranks of Mūsā and Hārūn, peace be upon them. So all such people are certainly bound by this command to speak “with gentle words” to people in authority and to people in general. One reason for that adab to people in authority is that no one who has not experienced that responsibility can understand what such people face, both from their governance of societies with huge varieties of people in them, as well as from the political configuration of the world today.

There is however much importance attached to the ability of the people in authority to advance the dīn, because of a well-known saying – “Allah prevents by means of the man in authority that which He does not prevent by means of the Qur’ān,” variously ascribed to the Prophet, peace be upon him, although without isnād, and more securely to ‘Umar, ‘Uthmān and ‘Umar ibn ‘Abd al-‘Azīz. This contains a profound truth.

And this brings us back to our theme: usurocracy. If we do not wish a usurocracy which is the rule of chaos, what type of rule do we wish? Not democracy, since everyone has known since the time of Plato, Aristotle and Polybius that democracies conceal the actions of oligarchies, who are usually the wealthy and often usurers. Nevertheless, we are not ungrateful for the space of democracy that allows us to speak and even to act. We certainly do not wish for autocracy, the dictatorial will of a single person enforced on the population.

The person in authority ought to bring about, not the things that he himself wills, but the nomos of Allah and justice in the society. For that there must be another balancing force and this is not an institution in the modern sense, but an ethos that permeates Muslim society from top to bottom, that of mutual counsel – shūrā.

Since he is charged with bringing about order, not disorder, and since that requires knowledge, then he must have the counsel of people of knowledge, people of all sorts of expertise including women in areas they have particular knowledge of, diplomats, military strategists, merchants when it comes to commercial matters, fuqahā’ and people who have practical knowledge in general.

There is an important matter here: the independence of such people. If the counsellors are employed by the person in authority or the government, then they will not be independent in their counsel. Thus, they must either be people of independent means, and this was the model of the Mālikī fuqahā’ of Timbuktu who were themselves traders and independently wealthy, or they must be supported by the waqf-endowments that were always the backbone of Muslim society, an institution very far indeed from the ‘Ministry of Awqaf’.

The person in authority may forcibly prevent usury in the market-place, whereas the individual left to himself is less able to do that. However, we can also extrapolate from this in a positive sense, for the person in authority has the ability to establish a free market and dedicate it as a waqf, and to mint a sound currency and other matters that the individual would struggle to do, and these positive measures are the vital counter to the merely negative one of stopping usury without which it will not be effective. And people in authority may well be local mayors, perhaps even more than leaders of nation states, for paradoxically the local leader often has more freedom and real power than the national politician.

This is a power far beyond the merely preventative, which in itself is no small thing. The person in authority is charged with seeing that the prayer is established by appointing imams and mu’adhdhins, building mosques and appointing endowments to support all of that, by appointing zakāt collectors to take the zakāh, and to take it from the wealthy, the super- and hyper-wealthy, rather than it being, as it is today, a charity that conscientious people, usually of modest means, choose to pay to worthy causes that meet their approval. He must appoint qadis, people knowledgeable in the nomos of Islam, to see to its application, to arbitrate between people in the numerous domestic and business disputes that arise, and especially to appoint muḥtasibs to prevent injustices in the market in the widest possible sense of the term.

Economist and historian Michael Hudson, who also specialised in ancient history and the rise of usury in it, discovered that in the ancient world the harmful effects of usury were ameliorated to some extent by autocratic rulers who dominated the commercial class, and periodically cancelled outstanding debts. However, in the democratic era starting with the Greeks, the commercial class and their usury escaped from control, until today the ‘free market’ has been redefined as one in which there are no limits on the operations of capital and no limits on the actions of usury, although the ‘free market’ is far from free for anyone other than high finance.

It seems to me, and Allah knows best, that an age is coming to an end: the cold psychopathic age of scientistic detachment that has allowed the world to view with horror the genocide in Gaza or be indifferent to it or be moved, but in all cases completely unable to do anything about it.

Similarly, the age of Muslim modernism is over, since it has achieved whatever it could possibly achieve, which is the erection of a couple of states that are constrained within the Titanic patterning of nation-states today, forced to take part in the usury of the age and similarly to play ‘great-power’ games. The Titanic model of the nation-state sees them as sectioned off from each other by bulwarks such that if any of them are threatened by internal forces, they can be closed off from the world, as we have seen, and punished.

Abdalhaqq Bewley has suggested a kind of looser federation of Muslim states based on the common understanding of Islam that pertains from Indonesia to Senegal, that could implement one of the key components of a non-usurious economy, the minting of gold dinars and silver dirhams as a common currency. They could indeed also re-introduce open markets networked across the earth. That is based on the Muslims as the ‘midmost nation’ mentioned in the Qur’ān, and would, we pray, be the fulfilment of the words of Allah, exalted is He, “You are the best nation brought forth before mankind, you command the right and forbid the wrong, and you believe in Allah.”

Within that setting, the task of the future is to dismantle the modern state and the bank, first of all intellectually and philosophically, which activity must necessarily precede practice. That is not because we adhere to the idea of theory preceding action, but that rather here a theory must be unveiled, and carefully dismantled, with the care one would exercise in de-commissioning a nuclear power state. This negative approach, what in the science of kalam – the study of ‘aqida that articulates what may and what may not be said both rationally and textually about Allah and His Messenger, is characterised in its first steps as salbiyya, meaning that it strips away what is simply inconceivable for Allah, which one cannot imagine as being true. But this negative approach to the issues confronting us is, in the words of the author Conan Doyle: “Exclude the impossible, and what is left, however improbable, must be the truth.”

Now we have had three phases vis-à-vis our relationship with capitalism and the West: first, outright submission, either at the end of a gun or by voluntary internalisation of capitalism’s and modernity’s values; second, with the resurgence of some of our societies and the rise again of appreciation for our knowledge tradition and values, there was the thesis that we must take the best of both cultures and have a new synthesis. The cream of this approach is the traditionally trained scholar with a PhD from Harvard, Oxford or Stanford. The peril in this approach is that while the intention was the Highest Common Factor, the result has often been the Lowest Common Denominator.

Among the highest of Western thought has been that of Martin Heidegger who, along with many others, awakened to the perilous course we have been on since the foundation of the West’s thinking with the Greeks, among which were philosophy, metaphysics, the sciences, and politics – the thinking on the state. Poised between the two dangers of embrace and rejection, and initially positing what in German is called Gelassenheit – equanimity or composure, Heidegger would move on to a more nuanced position. He wrote: “Especially we moderns can learn only if we always unlearn at the same time. Applied to the matter before us: we can learn thinking only if we radically unlearn what thinking has been traditionally. To do that, we must at the same time come to know it.” (Heidegger, What is Called Thinking)

So it is this we need. Not merely to quote Weber, Hobbes and Leo Strauss, but to begin the task of learning/unlearning, only with a view to a step forward for the Muslims and mankind.

The intellectual and philosophical dismantling of state and bank is necessary for the human race, even if only to understand them properly. Democracy deceitfully fronts for usurocracy and, in spite of its name, acts against the interest of the dêmos – the people. Are we grateful for the freedoms afforded us in democratic societies to openly discuss these matters? Of course we are. But opening up the discourse may help us to understand also the concept of religion without priesthood and church, commerce without usury, and governance without state, in Shaykh Dr. Abdalqadir as-Sufi’s pithy expression. The understanding of that is the task of future Islam.