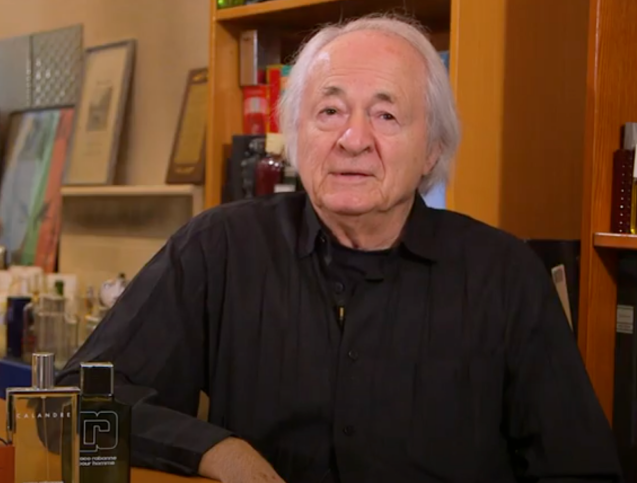

The legendary name behind perfume bottle design, Pierre Dinand, is a designer who sees fragrances not merely as scents but as stories told through form. The iconic bottles he created for brands like Dior, YSL, and Givenchy are not only aesthetically pleasing but also cultural expressions. We spoke with Dinand about perfume bottle design.

Let’s start by getting to know you. Could you briefly tell us about yourself and how you began working in the field of perfume bottle design?

I initially studied architecture at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris but didn’t continue as I wasn’t strong enough in mathematics. Soon after, I began working at a small advertising agency specialized in luxury goods—cognacs, fashion, and perfumes. One day, a client named Hélène Rochas asked if I could design her perfume bottle. I accepted, and it was a great success. Afterward, she introduced me to her circle of friends: Givenchy, Balenciaga, Cardin, Yves Saint Laurent, Dior, and Guerlain. I started working for all these iconic brands, and that work has continued uninterrupted for over 65 years—and it still goes on today.

How does the design process develop? How do you reflect the fragrance and the brand in your bottle designs? What inspires you?

I usually start with a blank page. Most of the time, the client has no clear idea and begins by asking basic questions: What color? What animal? What collection of objects? Visiting their apartment can also be very helpful.But in general, the bottle must reflect the client’s personality. It should be unusual and attractive—because it’s the first thing people see. In fact, 80% of the purchase decision is based on the design of the bottle. However, if the perfume isn’t liked, the client won’t buy it again. So, success is like playing a slot machine—you need six cherries to win. The six cherries are: good design, good perfume, marketing, distribution, and finance. If you get five cherries, you win. But if you get four cherries and one banana—you lose. So… NO BANANAS. I’ve been very lucky to be associated with so many successes. It’s truly amazing.

Which project challenged you the most in terms of design boundaries? Could you share a particularly exciting or technically demanding experience?

Throughout my career, I’ve had the privilege of collaborating with visionary designers, but if I had to name one project that truly stretched the boundaries of design, it would be Opium for Yves Saint Laurent. It wasn’t just about creating a container — it was about building an object of cultural tension and mystery.

I drew inspiration from Japanese lacquer boxes, objects that carried both elegance and ritual. Translating that into industrial production, however, was a battle. The technical constraints were immense: the unique curvature, the deep red lacquer finish, the magnetic closure — none of it had been done before.

There was also a symbolic weight. Some saw the design as provocative or politically loaded. But I believe the designer must not flinch at discomfort — tension is where meaning lives. Opium became iconic precisely because it defied expectations. It dared to look different, and in doing so, it became unforgettable.

What are the unique challenges of designing perfume bottles today? Have recent trends, market expectations, or production constraints changed your creative process?

The landscape today is far more complex than when I began. Back then, a designer could pursue poetry in form; now, we must negotiate with cost-efficiency, sustainability, and speed.

Clients demand innovation, but they also want predictability. There’s a paradox: you must surprise, but within a controlled, market-tested framework. Add to that the growing emphasis on ecological responsibility — materials must be lighter, reusable, recyclable. All this narrows the material palette and complicates the craft.

But limits aren’t the enemy of creativity — they are its crucible. Constraints force you to ask deeper questions about purpose and identity. I don’t mourn the old days. I adapt. Design has never been about nostalgia. It’s about making the invisible visible, under any condition. And that challenge remains as thrilling as ever.