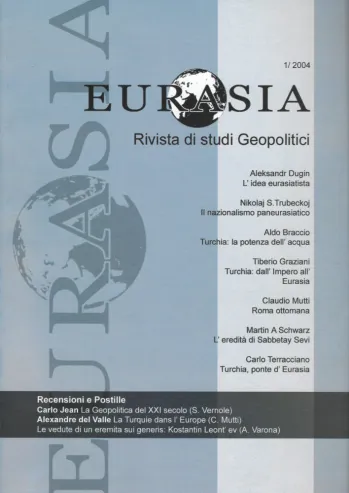

Claudio Mutti is an Italian scholar — a Muslim, a Traditionalist, and a Eurasianist — who continues to direct Eurasia Rivista. Over the course of his life he has crossed paths with many leading figures and has personally witnessed the decisive turning‑points of our age; this is his first interview conducted in Turkey. We covered a wide range of subjects, from Nietzsche to geopolitics, from Codreanu to Eurasianism, from Islam to the idea of a Mediterranean union.

For our readers in Turkey who may not know you, could you tell us something about yourself? How did your conversion to Islam and your relationship with the Traditionalist School shape your intellectual and spiritual journey? In what way did Julius Evola and the Traditionalist School influence your philosophical path?

I practised the Catholic faith until I was fifteen years old, when the abolition of Latin as the liturgical language and the change in religious rites led me to seek other ways of approaching the sacred. In this search I was greatly helped by the so‑called “masters of Tradition,” first Julius Evola, then René Guénon. Evola’s masterly work Revolt Against the Modern World presented Islam to me as a “tradition of a higher level not only than Judaism but also than the beliefs that have conquered the West”; René Guénon’s writings served as my compass for a deeper study of traditional doctrines and of Islam in particular. I moved from theory to practice when I pronounced the shahada at the age of thirty‑three.

What prompted you to write the book Nietzsche and Islam? Did you address Nietzsche’s ideas in a way similar to Muhammad Iqbal’s interpretations?

According to Muhammad Iqbal, the fundamental needs expressed in Nietzsche’s thought find complete fulfilment within the Islamic vision. The Gestalt (archetypal figure) to which Nietzsche gives the name Übermensch (Super‑man) is sublimated and perfected in the Islamic notion of the “servant of God.” Indeed, the Islamic Super‑man—the perfect human (al‑insān al‑kāmil) exemplified by the Prophet Muhammad—is called ʿabd, “servant,” at the moment of his greatest exaltation in the Qur’an (17:1), when he is borne toward the Divine Throne. Thus, according to Iqbal, the Übermensch is one who fully and actively identifies his own will with the Divine Will.

There are other fundamental notions in Nietzsche’s thought which, like that of Übermensch, find precise correspondences in Islamic doctrine. One example is the formula amor fati, a central pillar of Nietzsche’s conception of life. A hallmark of Islam is the awareness of the total dependence of manifestation upon its Divine Principle; hence the Muslim’s confident acceptance of whatever occurs in the universe. This attitude, which in no way excludes individual responsibility and is perfectly compatible with action, could rightly be defined with Nietzsche’s expression amor fati, especially when serene acceptance of the Divine decree (fatum) turns into love for Allah.

Corneliu Zelea Codreanu is an important figure in Romanian history, especially as founder of the Iron Guard. How do Codreanu’s ideas and actions relate to your views on nationalism and traditionalism?

The Iron Guard (the Legion of the Archangel Michael), whose nationalism and traditionalism lay in a close relationship with the traditions of the Romanian people, was not a political party in the modern sense but a movement animated by a religious, almost mystical fervour; not by chance were numerous Orthodox priests active in its ranks. Legionary ethics can be described as ascetic and chivalric, inspired by an ideal of sacrifice, self‑overcoming, and service to the people. In For the Legionaries Codreanu writes that the Legion must be more a school and an army than a political party and that from this school should emerge a “new man,” that is, a man with heroic qualities. After a long conversation with the Captain, Julius Evola likewise wrote that “the task of the Movement is not to formulate new programmes, but to create, to shape a new man, a new way of being.”

Is your interest in geopolitics linked to your Traditionalist thinking, or were there specific historical or intellectual reasons that led you to it?

A reflection by René Guénon on “sacred geography” and geographical symbolism led me to ask whether Carl Schmitt’s famous assertion—that “all the most significant concepts of modern state doctrine are secularised theological concepts”—can also be applied to geopolitics. In my view, certain key geopolitical notions can indeed be considered “secularised theological concepts.” Let me mention just one example. The Latin word limes, now adopted in contemporary geopolitical vocabulary (an Italian geopolitics journal is even called Limes), originally indicated a dividing line drawn between plots of land allotted to settlers; its meaning later broadened to denote a military road and, indeed, the entire system of fortifications on the Empire’s borders where those borders were not marked by sea or river. The supreme protector of the limes was the god Terminus, to whom Ovid addresses these words: “You mark the boundary between peoples, cities, and great realms.” Georges Dumézil showed that in ancient Indo‑European religion the name Terminus corresponded to a characteristic quality of the sovereign deity: the function of supreme guardian of territorial limits.

How does the geopolitical framework you have developed differ from Aleksandr Dugin’s concept of Eurasianism?

In Dugin’s perspective the Old World—the land‑mass of the Eastern Hemisphere—is divided into three great “vertical belts” running north‑south along the meridians: Eurafrica (Western and Central Europe, the Arab great‑space, sub‑Saharan Africa); the Russo‑Central Asian zone (former USSR, Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, the Indian subcontinent); and the Pacific zone (China, Japan, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Australia). This “vertical” geopolitical vision, which sharply separates Europe from Russia, was criticised in the pages of Eurasia by Carlo Terracciano, who observed that Eurasia is a “horizontal” continent, extending along the parallels. Translating this geographical fact into geopolitical terms, Terracciano—contrasting with Dugin—proposed integrating the great northern Eurasian plain from the English Channel to the Bering Strait. In such a perspective it is natural for Europe to integrate into an economic, political, and military sphere of cooperation with Russia; otherwise it will be used by the Americans as a weapon against Russia.

“If we can and must still speak of West and East,” Terracciano concluded, “the line of demarcation must be drawn between the two hemispheres, between the two continental masses separated by the great oceans,” so that the true West, the land of sunset, turns out to be America, while the East, the land of light, coincides with the Old Continent.

Despite his “vertical” conception, at odds with a common Eurasian destiny, Dugin was nevertheless well aware that Eurasia is under attack from U.S. thalassocracy, which by its very nature (and not merely by the orientation of one part of its political class) has always been driven toward world dominion.

But in 2016, when Donald Trump’s first presidential campaign began, Dugin set aside the geopolitical viewpoint and adopted a predominantly ideological one, identifying globalist liberalism as the “main enemy” and greeting the election of the “conservative” and “isolationist” Trump with unbridled enthusiasm. “For me,” Dugin said in November 2016, “it is obvious that Trump’s victory has marked the collapse of the global political paradigm and, simultaneously, the beginning of a new historical cycle … In Trump’s age anti‑Americanism is synonymous with globalisation … anti‑Americanism in today’s political context has become part and parcel of the rhetoric of the very liberal elite, for which Trump’s arrival in power was a real blow. For Trump’s opponents, 20 January was ‘the end of history’, whereas for us it represents a gateway to new opportunities and options.”

Continuing along this path, on 3 January 2020 Dugin even wished Trump “four more years. Keep America great”—on the same day Trump proudly claimed responsibility for the assassination of General Soleimani. Thus Dugin has advocated a “new alliance” between Russia and the United States. “The enemies of Russia,” he wrote on 20 May 2025 on the Katehon site, “are the enemies of Trump, and the enemies of Trump are the enemies of Russia. Indeed, our new relations [between Russia and the USA] should be built on this rejection of globalism. And perhaps even our new alliance.”

Leaving Eurasianism aside, I would like to discuss the idea of a Mediterranean union. Do you believe it is possible to create such a union? What do you foresee for the future of Italy and Turkey in the Mediterranean context?

Since the Second World War the Mediterranean has been dotted with NATO and United States military bases—from Málaga to Sigonella, from Alexandria to Izmir to Cyprus—turning it into an inlet of the Atlantic Ocean, practically a lake under North‑American domination. Added to this is the presence of another foreign body that continually causes destabilisation and conflict: the criminal Zionist regime that has occupied Palestinian territory for eighty years. In such a situation a “Mediterranean union” would have decisive meaning only if its purpose were a concerted action to expel these alien presences from our mare nostrum. But which Mediterranean country could undertake such an initiative? The front‑line role would surely fall to the four Mediterranean peninsulas: Spain, Italy, Greece, and Turkey. The last, in particular, occupies a geographically crucial position, for the Anatolian peninsula—situated at the centre of the great continental complex—is the natural crossroads between Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Considering that the first issue of your journal Eurasia was dedicated to Turkey, where does Turkey fit into your geopolitical theory?

The region the Byzantine Greeks called Anatolia (“land of the rising sun”) was in antiquity regarded as an integral part of Europe: Herodotus set Europe’s eastern boundary at the Phasis River, near today’s Georgian ports of Poti and Batumi. In the Middle Ages Dante placed “the extremity of Europe” near the mountains of Asia Minor, from which, after Troy’s destruction, the Imperial Eagle flew toward Italy. In the nineteenth century the geographer Élisée Reclus said that Anatolia is a land of Asia set into a European coastline, while simultaneously linking south‑eastern Europe to the Eurasian land‑mass.

If the Anatolian peninsula is the western‑most projection of Asia, it is at the same time the fourth Mediterranean peninsula, occupying a position analogous to those of Greece, Italy, and Iberia; in relation to the latter, Anatolia stands in a mirror position, so that the two peninsulas can be regarded as the guardians of the Mediterranean. Yet Turkey is not only Anatolia; Turkey is also Constantinople, former capital of what Arnold Toynbee called “a Turkish Muslim Roman Empire.” In short, Turkey is a quintessentially Eurasian country, straddling both Asia and Europe. Therefore, when people say that Turkey must choose between Europe and Asia, they pose a false dilemma. In my view, the choice before Turkey is between Eurasia and the West.

Do you believe a Muslim European identity could emerge, given that anti‑Islamic and anti‑Muslim sentiments have played a significant role in shaping European identity throughout history? How should the rising Right and Muslims in Europe approach each other?

While the Left has carried out an insidious strategy of contaminating Muslim communities, there is no real willingness on the part of right‑wing movements to come closer to Muslims, nor any inclination in that direction. Fundamentally Occidentalist, the Right adopts pro‑Islamic positions only in situations where a particular Muslim reality happens to converge with Western interests—as was the case, for example, in Afghanistan during the anti‑Soviet guerrilla war or in the ethnically torn Yugoslavia. Conversely, wherever a Muslim people’s stance clashes with that of the West, the Right (with the exception of some negligible fringe of the extreme Right) is invariably found in anti‑Islamic positions. Certainly, the European Right could establish an understanding—or at least a dialogue—with Muslims by proposing a common defence of the moral values attacked by the culture now dominant in the West. Why does it not do so? Either through obtuseness, or cowardice, or because it judges that pseudo‑identitarian demagogy is more profitable in electoral terms.

Where do Conservative Revolution and Traditionalism converge and diverge, in your view? Do you think this line of thought can effectively challenge or halt the advance of secular liberalism?

The formula “Conservative Revolution” (Konservative Revolution), born in German circles after the First World War, was meant to signify action aimed at eliminating a condition of disorder in order to restore a state of normality. Today, however, given the depth to which so‑called “Western civilisation” has sunk, it should be clear that little remains in Europe that would deserve to be conserved. As for the concept of revolution, if it is to be understood in its etymological sense, one is inevitably led to think of a return (revolutio) to those fundamental principles denied by modernity. In that case Traditionalism, to be meaningful, cannot be conceived as homage to residual forms and institutions handed down from the past, but rather as an aspiration to a new beginning. Therefore, instead of a “Conservative Revolution” we should theorise a “Traditional Revolution” inspired by a “Revolutionary Traditionalism.”

Since the 1980s, post‑modern attitudes have gained considerable momentum. Do you think post‑modernism has created room for the re‑emergence of tradition and Traditionalism, or has it rather diminished their influence?

Post‑modernity is not the overcoming of the modern world, but its supreme phase, in which nihilism is fulfilled through the subversion of nature and the technologisation of man, who is indeed surpassed—but downward, toward the infra‑human. If one wishes to resist this artificial and inverted “order,” one must first act upon one’s own consciousness, so as to be able to reject every deception and every seduction, every temptation to surrender or neutrality, and then behave accordingly. That the culminating stage of modernity might facilitate the re‑emergence of tradition may seem paradoxical, but in the end it is a necessary prospect, because from the traditional spirit can come the strength needed to refuse submission to an unreal world.

Do you intend to write your memoirs?

Standing on the threshold of eighty, I ought to write Confessions of an Octogenarian. But a book with that title already exists: it was written by Ippolito Nievo between 1857 and 1858.