Although J.R.R. Tolkien, a prominent figure in fantasy literature, and Julius Evola, a leading voice of Traditionalist thought, may seem distant at first glance, the intellectual journey of Gianfranco de Turris builds meaningful bridges between these two realms. In our conversation with Turris, we explored a wide range of topics—from the intersections between Tolkien and Evola, to the potential of fantasy to create a “secular myth,” from the mythopoietic effects of the digital age to Tolkien’s place within the Italian Right.

Could you briefly introduce yourself and tell us how your interest in fantastic literature was born?

It’s a bit difficult to introduce oneself briefly when one has been writing, publishing, and working for over 60 years—having started in 1961—and has accumulated so many experiences. I can say that I have overseen the Italian edition of hundreds of volumes (including the opera omnia of Julius Evola), often writing the introductions; that I have directed series of science fiction and occult books; that I have worked as a journalist both for the printed press (newspapers and magazines) and for RAI, the public entity responsible for radio and television in Italy, working at the Radio News where I was for 25 years and where I conceived and hosted cultural programs; that I have written over twenty non-fiction and fiction books; that I now direct a magazine dedicated to the Imagination; and that I have done much else that I no longer remember…

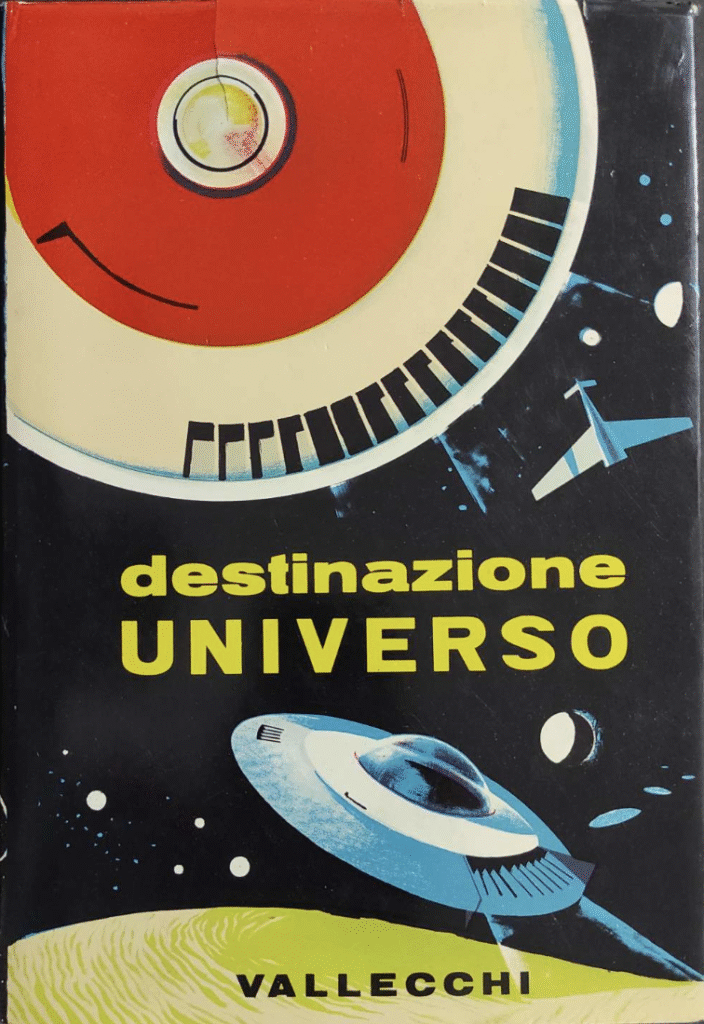

I can say that my passion for fantastic literature has always existed: ever since I was a boy I preferred reading Jules Verne to Emilio Salgari, and it continued that way throughout my life, ignited in 1957 when I was given Destinazione Universo, edited by Piero Pieroni for Vallecchi, and then taking shape years later when I began writing stories and articles at 16, when I was in high school. The reason was simply what many consider a negative fact, namely the so-called “escape from reality”: I did not like the world around me at all from a very young age and I looked for a better one, which is not at all reprehensible, as Tolkien himself explains precisely in his essay On Fairy Stories, written to reply to the criticisms he received when The Hobbit came out in 1937.

Moreover, what especially interested me and my lifelong colleague and friend, Sebastiano Fusco, was raising the tone of science fiction and the fantastic, no longer to be considered B-grade literature or even Z-grade literature. To achieve this, in the 1970s, for the “Futuro” and “Orizzonti” series we created for the publisher Fanucci of Rome, we wrote about a hundred essays—not simple brief introductions—to be placed before the novels and anthologies we curated, in which, for the first time in Italy, we utilized the symbolic method to interpret and valorize them, that is, the method derived from the systems of thinkers such as Mircea Eliade, Joseph Campbell, Julius Evola, René Guénon, Otto Rank, and others—something that until that moment had never been done in Italy and at that level, and which aroused amazement but also many criticisms, strangely of a “political” nature… However, after about forty years we can say that we achieved our goal: to bring the literature of the Imagination as a whole to the same level of appreciation and acceptance as “realistic” literature. In fact, in recent years a couple of volumes with “the best” of these essays of ours have been published.

In what way did your path intersect with that of Julius Evola and, as a representative of the traditionalist current, what approach did Evola have toward fantastic fiction?

At the bottom of this question—as has often happened to me—there is the implicit request for an explanation of my simultaneous interest in fantastic literature and the traditionalism embodied by Evola.

I discovered his works in 1968–69 when they began to be reprinted by Edizioni Mediterranee, because previously they were practically unobtainable, and I was struck as if by lightning. Then Adriano Romualdi took me to his house and I met him in person and he grew fond of me, and I was essentially the one who managed to interview him the most during the remaining years of his life, that is, until 1974. The first interview came out in 1970 and then the others followed (all gathered in a volume), which so to speak “popularized” him in a certain milieu; otherwise he would have remained in the ghetto of his die-hard followers, who are not always the best, given that they often have—let me say it without pretense—blinders on and tend to consider him as “their property.”

And what link is there with the fantastic from my point of view? Essentially, as I have always said, I found in Evola’s works the values—I emphasize, the values—that were found (and that I had found) in the best fantastic literature, that is, in the so-called “heroic fantasy,” in the sagas, in the epics; hence the connection, which, I repeat, is a connection of values and certainly not of subjects (see, for example, the values expressed in The Lord of the Rings).

Evola’s approach to the fantastic was very particular: he was not interested in the literary genre in itself but only in that which had a symbolic value or an esoteric or occult content. For example, I tried to get him to read Lovecraft but he was not impressed at all, since according to him Lovecraft did not possess that background, whereas he was extremely interested in and passionate about Gustav Meyrink, who did possess it and used it constantly in his novels, occult and fantastic together. In fact, it was precisely he who translated him into Italian in the 1940s. This interest remained with him over time; so much so that he invited me to collaborate with him on the Cahier de l’Herne dedicated precisely to Meyrink, even if the volume came out only after his death, if I remember correctly.

In your opinion, is contemporary fantastic literature truly building a “secular myth,” and what differences do you see between this new narrative and traditional religious myths?

The definition of “fantastic literature” is very generic, especially today, and includes everything and more, and the most bizarre and heterogeneous things among themselves. To build a “secular myth,” as you say, I think a much more uniform and unidirectional fantastic literature than the one that exists would be necessary. I therefore do not believe that it can realize that “secular myth” you speak of, and so the difference between past and present lies precisely in these two adjectives: today’s secular is yesterday’s religious; they are the opposite of each other, and therefore a “secular myth” could only come about if world fantastic literature had common bases, common perspectives, common goals, even simply indirect and not explicit, which to me seems not to exist because it is totally independent depending on the individual countries in which it is produced, and the English-language fantastic literature is quite different from the French or German or even Italian one, where moreover the places of publication are extremely scarce.

Paradoxically, however, what I have just stated may have a counter-proof: what literature does not seem to succeed in achieving, in a certain sense cinematography has achieved with its sagas, that is, a story with an epic tone on a wide scale with symbolic bases: I think of Star Trek but above all of Star Wars, which is no coincidence has as a background the theories and ideas of the scholar of religions Joseph Campbell. And Star Wars, with its multiple trilogies, which have influenced at least two or three generations of viewers, has probably achieved a result that was unimaginable for literature. Apart from, of course, the overall work of J.R.R. Tolkien, which is immense and ultimately presents itself as a cosmogony and which, precisely in the professor’s intentions, was supposed to serve as a founding myth for his country, which he believed was lacking one. Who knows, perhaps something similar to that “secular myth” you were talking about…

The Lord of the Rings was first adopted by the hippies and today is appreciated by more secular audiences: how do you explain that a Catholic and conservative author like Tolkien finds resonance among such different readers?

Precisely because of the word you used! But we must consider it in its original Greek etymology, where katholikos means “universal,” as I have often recalled over the years. Tolkien is appreciated by everyone precisely because he is a universal author; he deals with universal themes and values, and his books are translated into about thirty languages. Which means he does not speak only to “Westerners.” In his characters anyone can identify themselves, whatever they believe in. Not for nothing did he complain “of my deplorable cult”!

It is worth noting on this occasion that when Tolkien’s masterpiece was released in Italy, now more than half a century ago in 1970, it was attacked by the progressive culture led by Umberto Eco for a series of reasons: the fact that it dealt with a medievalizing era and therefore was obscurantist in terms of values, and because it was published by a publisher considered “right-wing,” Rusconi, and edited by intellectuals also considered right-wing, such as Alfredo Cattabiani, Quirino Principe, and Elèmire Zolla. And an intellectual like Walter Pedullà went so far as to say that a “cordon sanitaire” had to be created around Rusconi…

This, let’s call it a preventive barrage, meant, as many later testified, that left-wing kids had to read it in secret, while those on the right “adopted” it, as I said (certainly they did not “instrumentalize” it, as they were unjustly accused of doing, because one does not “instrumentalize” what one identifies with), both as an adventure story and as myth and symbol. So much so that at the end of the decade they organized Hobbit Camps in the summer, which were certainly not paramilitary camps as they were accused of at the time, and it was shown that they were not, and a musical group active until very recently was born, called “La Compagnia dell’Anello” (“The Fellowship of the Ring”). Such was the extent to which the young right of the time was affected and influenced by Tolkien’s imagery….

Do you believe that The Lord of the Rings symbolically represents the Second World War, Catholic theology, or something else? Which interpretation do you consider more convincing and why?

The Lord of the Rings has always been the subject of comprehensive interpretations, but first of all the author himself denied that there was an allegory of the Second World War—for example, Sauron as Stalin, a hypothesis that had been advanced by someone. Generally, however, and in a very banal way, the novel is considered as the representation of the struggle between Good and Evil, but in my opinion, as I have always said, it is not so: it is essentially the concrete and symbolic opposition between the beneficial Power and the malevolent one, between the positive Power and the negative one (Tolkien was neither an anarchist nor a liberal), represented by the main characters of the work, and this is probably better understood in the conclusions of the “longest fairy tale in the world,” as Lester del Rey defined it, from the relationship between the two Powers that clash and from the symbols that Tolkien adopts, for example the two towers, and also considering the choices made by the main characters.

In your book on Evola and Tolkien, which common themes emerge most strongly, and are there indications of direct or indirect interactions between the two?

There have not been more different people than Evola and Tolkien, both humanly and ideologically and, essentially, politically as well, yet they were united by a single point of view that I highlighted in my book, namely their anti-modernity, which in each of them manifested itself according to their personal characteristics. Both were against machinism, against technology, against mass civilization, against mass tourism in particular, against the destruction of nature. All this, up to this moment, had not been noticed and highlighted, perhaps due to the great diversity between the two authors, and it had not been emphasized and commented upon, something that I did for the first time very punctually with precise references. But despite everything, my comparison raised criticism and often indignation from the “orthodox” of one side or the other. Who knows for what hidden reason…

If by “interaction” one means relationships, connections, and the like, the answer is negative. As far as I know, even though they were contemporaries (they died one year apart, 1973 and 1974), there were no contacts of any kind between them; even though Tolkien made his famous trip to Italy, they did not meet and neither of them read the works of the other.

In your opinion, has contemporary Italian political right been influenced by Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings, both on a symbolic and ideological level?

I mentioned earlier the problem and how the Italian right of the 1970s and 1980s “adopted”—that is the term I have always used—Tolkien and was influenced by him, but we are talking about almost half a century ago, and the right of today is not that of yesterday. Certainly the book, its author, and the characters with the spiritual values they represent have been a point of reference also for the subsequent right, and in fact, if I remember correctly, this was thrown in the face of the current Italian premier as well, but that’s stuff from times past. Today I must say with regret that the right that came to power in 2022 seems to me to be forgetting those metapolitical teachings and is dealing mainly with the practical power it manages, it seems to me with very little idealism especially in the intermediate ranks. Obviously, the management of power consists of concrete facts rather than ideal daydreams, but behind it there must be something else, right?… Fortunately, some exponents of the current government possess it, and precisely for this reason they are often targeted by opponents. I hope they hold on…

Finally, how do you imagine that the mitopoietic potential of fantastic literature will evolve in the digital age?

Exactly, digital age. This is the key word, also because even if it is a very sophisticated technology, digital is always a technology, and how will it influence the fantastic in its multiple aspects, more than fantastic literature in particular? How will it influence it, how will it manipulate it, how will it direct it? And what will be the new reference points for writers, comic book artists, illustrators, directors, film screenwriters, television series screenwriters?

On the one hand, consider what we already know, for example what has been achieved with superhero films and the like and in general with science fiction and fantastic films: things never seen before, thanks to artificial intelligence and therefore to digital. But on the other hand, consider how it has been possible to create from scratch plausible facts that never happened, with real personalities as protagonists: for example, years ago the arrest of Donald Trump when he was not yet president, and now what President Trump of the USA has had made with the arrest of his predecessor Barack Obama. It all seems very true and instead it is all completely false thanks precisely to the digital option.

Will what you define as the “mitopoietic potential” withstand the shock wave of the digital? Or will it be manipulated and modified?

I only hope that the “mitopoietic potential,” which is a heritage of humanity, continues to resist without being distorted, as it has resisted the evolution of changes over the centuries by adapting to the new cultures that arose from time to time, but there is a fundamental difference that is proper, as will have been understood, to the new medium: digital is in itself immaterial and, essentially, can do everything. Previously it did not exist and now I wonder if it could not negatively influence, without almost anyone realizing it directly, the “mitopoietic potential.” For me, it is something distressing because on its resistance to the omnipotence of digital technology depends the resistance of a mental universe that, after all, has made man what he is…