Larry Eugene Jones is an American expert on modern European history, an emeritus professor at Canisius College (Buffalo, NY). He is a leading authority on the political parties, associations, and conservative-nationalist movements of the German right during the Weimar Republic. He is best known for German Liberalism and the Dissolution of the Weimar Party System, 1918-1933 (1988), and later edited The German Right in the Weimar Republic (2013) and authored The German Right, 1918-1930* (2020, Cambridge University Press), which are foundational reference works in the field. We talked about Edgar Julius Jung, one of the important names of conservative revolutionism.

What theoretical contributions did Edgar Julius Jung make to conservative revolutionary thought? What were Jung’s original concepts or approaches? How did he search for nationalism and conservatism?

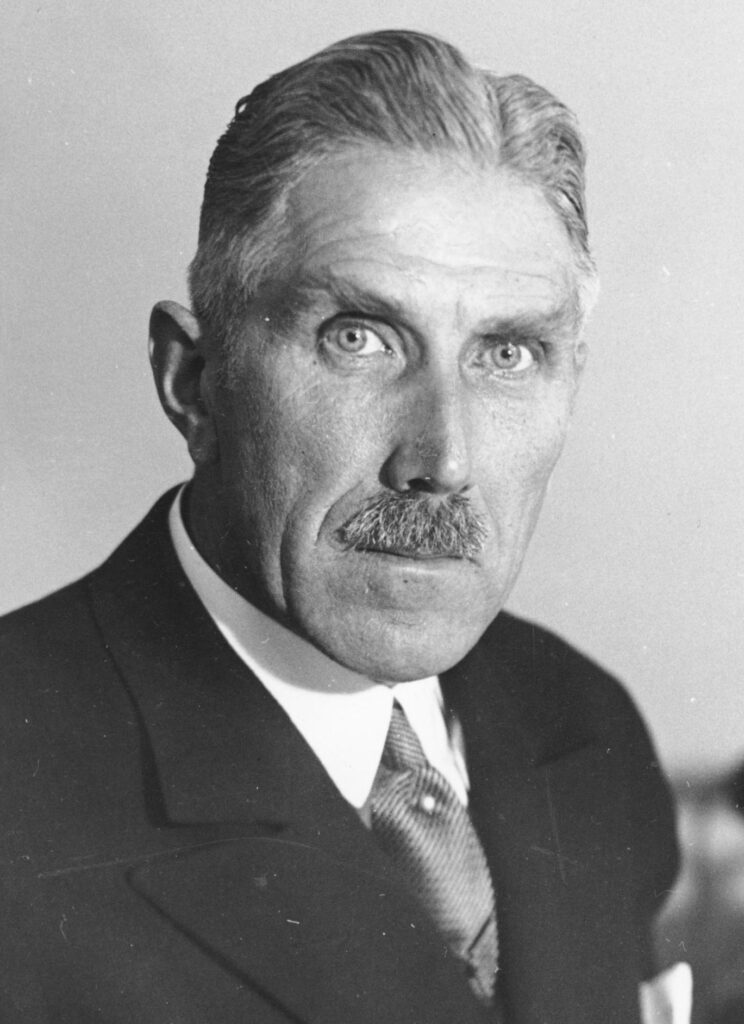

In discussing Edgar Julius Jung’s contributions to conservative revolutionary thought, it is important to remember from the outset that unlike most of those who liked to fashion themselves as “conservative revolutionaries,” Jung was first and foremost a political activist who sought to translate conservative values and ideas into political practice. Jung, who was born in 1894, had served at the front in World War I and proudly saw himself as a member of the “front generation” that sought to reshape Germany’s political life in light of their experiences at the front. Jung himself served as an assistant to Alfred Zapf, a newly elected member of the Reichstag who belonged to the liberal German People’s Party (Deutsche Volkspartei or DVP). As the political and economic crisis of the Weimar Republic drew to a head in 1923 and 1924, Jung resigned his post with Zapf in late 1924 after two unsuccessful runs for a seat in the Reichstag. In the meantime, Jung began to devote himself to what he saw as his sacred mission in German political life, namely, the unification of all those disparate conservative elements that had lost their faith in the politics of postwar German conservatism and were looking for new forms of political expression. At the same time, Jung offered tangible proof of his commitment to activism by his involvement in the assassination of the Palatine separatist Heinz Orbis in January 1924.

Throughout the second half of the 1920s Jung did his best to unite those who shared his disillusionment with the existing world of party politics into a new conservative movement based upon the experiences that his generation had shared at the front during World War I. To provide the theoretical foundation upon which this was to take place, Jung published what would become his magnum opus in a book aptly entitled Die Herrschaft der Minderwertigen: Ihr Zerfall und ihre Auflösung durch ein neues Reich, first in 1926 and then in a longer and more substantive edition in 1930. The book was an immediate success and catapulted Jung into the leadership of those in the younger generation who felt estranged and abandoned by the elites of Weimar Germany. Jung drew upon the corporatism of Othmar Spann, the elitism of Vilfredo Pareto, and the organicism of the German romantics to forge a sustained assault against those ideas he held responsible for the decay of European society over the course of the previous hundred and fifty years. In particular, Jung cited the revolutionary motto of liberté, egalité, fraternité as the ultimate source of the problems that plagued the Europe of his day. To Jung the spirit of 1789 was a corrosive force that threatened to dissolve the fabric of European society into an amorphous mass of competing social and economic interests. Nowhere was the fragmentation of modern society more apparent than in the plethora of political parties that had accompanied the introduction of democracy in Germany and the rest of Europe. Politics in the modern age was nothing more and nothing less than the pursuit of special economic interests by parties that no longer strived to represent the welfare of the nation as a whole but the special economic interests of those factions that had been able to gain control of the state political apparatus. To counter the fragmentation of modern political and economic life, Jung offered a vision of the state and society that he traced ultimately to the organic character of the medieval world. In this respect, Jung called not only for the restoration of the corporations that had played such an important role in medieval economic life but also for the return of religion to the place of honor it had held in medieval Europe. And this, Jung concluded, could only be accomplished by a revolution that, unlike the Marxist revolution that simply sought to improve the material conditions of human life, sought nothing less than the rebirth of the human spirit.

For Jung, the root of the evil that beset the modern world was the doctrine of natural rights and its triumph not just in revolutionary France but in Germany with the collapse of the Second Empire in the fall of 1918 and the founding of the Weimar Republic a year later. In this respect, however, Jung did not call for a return to the politics of the Second Empire or for the creation of a more perfect German democracy, but for a revolutionary new conservatism that would entail nothing less that the spiritual rebirth of the German nation. This, in turn, would allow Germany to assume the leadership of Europe’s struggle against the crass nationalism and spiritual poverty of the modern age.

Why did Jung argue that the French Revolution had spiritually destroyed Europe and that Germany should be the spiritual and political centre of Europe, referring to the Holy Roman Empire?

Here we get at the religious core of Jung’s political thought, something that sets him apart from the majority of those who portrayed themselves as “conservative revolutionaries.” In this respect, Jung was profoundly influenced by Leopold Ziegler, a philosopher and theologian who had gained Jung’s trust in the last years of the Weimar Republic and who became, in many respects, his spiritual mentor. Though without the benefit of an academic position, Ziegler had distinguished himself as a critic of western rationalism who sought to restore Christianity to the sacred place it had enjoyed in the spiritual life of Europe before the so-called Age of Reason and the French Revolution. This, in turn, prompted Jung to rethink much of what he had written in Die Herrschaft der Minderwertigen, particularly in so far as it alerted him to the importance of the spiritual dimension of what he hoped to accomplish with his critique of Germany’s political development since the end of the eighteenth century. More importantly, Jung’s concept of Christianity was not narrowly sectarian but embraced both Catholicism and Protestantism in its various iterations. Nor was the unification of Christianity directed against the Jews, who did not figure prominently either as villains or victims in Jung’s analysis of the spiritual crisis that had descended upon Christian Europe.

Jung never abandoned his crusade to unite the forces of nationalism and conservatism under the banner of a revolutionary conservatism that sought to restore Christian values to the place he claimed they deserved in German state and society at large. But by the last years of the Weimar Republic it had become increasingly clear to Jung that this would never happen within the framework of the existing political system. Jung’s efforts to establish a foothold for his cause in the People’s Conservative movement of the early 1930s ended in failure, and he turned his energies once again to the establishment of young conservative clubs throughout Germany in hopes that this might serve as the organizational framework for a new conservative party based upon the principles of revolutionary conservatism. In the meantime, Jung continued to publish under his own name in the Deutsche Rundschau and under the pseudonym Tyll in the Westfälische Zei-tung. Here he began to focus more and more of his attention on Adolf Hitler and the rise of National Socialism. Jung was bitterly opposed to National Socialism and felt nothing but disdain for those bourgeois politicians who were searching for some sort of accommodation with the Nazi movement. Jung was particularly alarmed by the outcome of the Reichstag elections of September 14, 1930, when the Nazis received more than six million votes – or 14.6 percent of the popular vote – and elected 104 deputies to the Reichstag. Jung was fully aware of the implications this held not just for his own efforts to unite those who had become disillusioned with the Weimar Republic under the banner of revolutionary conservatism but for the very future of Germany itself.

For Jung there was a direct correlation between the rise of National Socialism and the crisis of western culture that could be traced back to the Enlightenment and the French Revolution. The triumph of reason and the disintegrative effect of the doctrine of natural rights on the values and institutions of western Europe had created a situation in which anti-humanistic movements like Marxism and Nazism could take root and grow. Only a return to the Christian culture of the late middle ages and to the hierarchical social order that went hand in hand with it, Jung argued, could rescue Germany and the rest of Europe from the nihilism of the modern age.

How did they influence each other with important figures in conservative revolutionism (Oswald Spengler, Ernst Jünger, Carl Schmitt)?

As strange as it may seem, it was not in Jung’s nature to get involved in public disputes with those with whom he disagreed. He was far more interested in tackling the issues at hand than in becoming involved in ideological disputations with those with whom he disagreed. To be sure, Jung writes somewhat disparagingly of Spengler’s pessimism in Die Herrschaft der Minderwertigen, but he does not expand upon it or disparage Spengler’s influence as a whole. And while Jung and Jünger both served at the front in World War I and shared what was commonly called the “front experience,” they drew different political conclusions from what this experience was supposed to mean. There was a positive reference to Schmitt’s Die geschichtliche Lage des heutigen Parlamentarismus (1926) in Jung’s Die Herrschaft der Minderwertigen, but there is no evidence that they ever corresponded with other or reviewed each other’s work. The two, however, had a bitter exchange at the third sociological conference of the Catholic Academic Association (Katholischer Akademikerverband) at the Benedictine Abbey in Maria Laach in July 1933 that had been convened in large part to facilitate an accommodation between German Catholicism and the Nazi state. Schmitt took particular umbrage at Jung’s suggestion that the Nazi party should follow the example of the German Center Party (Deutsche Zentrumspartei), the political party of German Catholicism, and dissolve itself to create a true state without parties. The two thinkers to whom Jung expresses his greatest debt, on the other hand, were Arthur Moeller van den Bruck and Nikolai Berdyaev. Moeller van den Bruck was the author of the phrase “An Liberalismus gehen die Völker zugrunde” and of the enormously influential book Das Dritte Reich. Berdyaev was a Russian religious thinker who was expelled from the Soviet Union in 1922 and is widely regarded as a founder of Christian existentialism. And in the last years of his life Jung came under the increasing influence of Leopold Ziegler, a philosopher and theologian who one might describe at the risk of over simplification as a Christian existentialist.

The origins of Jung’s own thought are extremely complex and cannot be reduced to a common denominator. He was adept at taking ideas from a diverse range of philosophers, theologians, and political thinkers and incorporating them, as disparate as they might have been, into his own view of the world and politics.

Can you talk about Jung’s criticism of democracy in Die Herrschaft der Minderwertigen? How did it differ from Carl Schmitt’s critique of parliamentarism?

Aside from their exchange at Maria Laach. I know of no record of what Jung and Schmitt might have thought about each other’s work. From what I know of Schmitt, it seems that his rejection of parliamentary democracy – he remained a Catholic, while Jung thought of himself as a disciple of Jean Calvin’s theology – had far less to do with religion than it did in the case of Jung. Whereas Jung has a romanticized view of the middle ages and longed for a return to a time before the age of liberalism and parliamentary democracy, Schmitt was much more hard-minded as a constitutional theorist and had little patience for Jung’s evocation of the past as a model for the future.

Edgar Jung was murdered on the Night of Long Knives in 1934. What made him such a threat to the Nazi regime?

In many respects, Jung’s voice was a voice in the wilderness. To be sure, Jung had built up a loyal following in the young conservative clubs that he had succeeded in founding throughout Germany since the middle of the 1920s, but this was hardly sufficient for the kind of influence he sought to wield. It was not until the summer of 1932, when Jung had the audacity to approach Franz von Papen shortly after his appointment as chancellor about a position in his government, that his prospects began to change. Papen immediately engaged Jung as his speech writer without making him a member either of his cabinet or official support staff. This nevertheless afforded Jung something he had never enjoyed before, access to power and the opportunity to influence the national government from within. Even though Jung authored a number of the speeches that Papen delivered through the summer and fall of 1932, he had little direct influence over the policies of the cabinet itself. Following the Reichstag elections of July 31, 1932, in which Hitler and the Nazi party received over thirteen million votes and elected 230 deputies to the new Reichstag, Papen hoped that the Nazis might be enticed into supporting his government only to discover that Hitler would settle for nothing less than his own appointment as chancellor. When new elections on November 6, 1932, failed to change the parliamentary calculus despite substantial Nazi losses at the polls, Papen’s fate as chancellor was sealed, and he resigned his position as chancellor only to be succeeded by Major General Kurt von Schleicher, who was no more successful than his predecessor in producing a Reichstag majority. For his own part, Papen fumed over the way he had been treated by his former ally Schleicher and entered into secret negotiations with the Nazi party leader that culminated on January 30, 1933, in the installation of a new cabinet with Hitler as chancellor, Papen as vice chancellor, and conservatives of one sort or another holding all but two of the remaining cabinet posts. Deeply distressed by this turn of events, Jung offered his services once again to Papen in the hope that he could assist the vice chancellor in building a conservative bastion around the vice chancellor that would keep the Nazis at bay. New elections were set for March 5, 1933, and Jung soon found himself busy at work as Papen’s speech writer. He would remain in this capacity for the next fifteen months without becoming part of the government itself.

This section will focus on three texts from the last year of Jung’s life in an attempt to develop a better sense of just where his thought was headed. Nowhere was the Christian component of Jung’s later thought more apparent than in the concluding chapter of a pamphlet he published in late 1933 bearing the title Die Sinndeutung der deutschen Revolution. Here Jung was quick to challenge Nazi claims that it was the sole embodiment of the national revolution by reminding his readers that the national revolution drew its impetus from two impulses, one nationalistic and the other conservative. Chastising the Nazis for having taken the national revolution down a democratic path, Jung insisted that the aim of this revolution should have been “the depoliticization of the masses and their exclusion from the leadership of the state.” Only through the founding of a new party based on religion and a universalistic view of the world, Jung argued, would it be possible for Germany to overcome the spirit of 1789. Conservatives, Jung continued, must assume leadership of the revolution and push it in the direction of an even more spiritual and religious transformation of man and society. Whereas all National Socialism had to offer was a world view, or Weltanschauung, as a substitute for genuine religious faith, it was time for German revolution that had accomplished its historic mission with the destruction of the Weimar state to transform itself into a Christian revolution.

In the meantime, Jung was still struggling with the chronic depression that had afflicted him since the conference in Maria Laach in the summer of 1933. This began to change when he received an invitation to speak at the University of Zurich in February 1934. Jung took advantage of the fact that he was no longer in Germany to speak more freely about the situation in his homeland than would otherwise have been the case. Without directly referring to the state of affairs in Nazi Germany. Jung dismissed both Fascism in Italy and National Socialism in Germany as transitional stages in the emergence of a new political order whose moral ethos was to be infused by a return to the Christian values that lay at the heart of all western culture. “Fascism and National Socialism,” Jung argued, “are political phenomena behind which great ideological forces are slumbering. The course which the dialectic of history has assigned to these revolutionary currents, however, leads past the present to the overcoming of the masses, the creation of a new society, the transcendence of nationalism, the establishment of an indestructible völkisch foundation from which the völkisch struggle can take form.”

By far the most important statement of Jung’s political credo following his return to active political life at the beginning of 1934 was a lengthy memorandum he drafted for Papen in early April. In elaborating upon the goals that animated the conservative opposition to Hitler, Jung went beyond his all too familiar diatribes against the legacies of the French Revolution to redefine the issue in distinctly racist terms that tied the future of white supremacy in Europe to the outcome of the struggle for the Christian-conservative regeneration of western culture. In this respect, Jung called for an end to the European nation state as it currently existed and for the emergence of a new European order in which centralized power would be redistributed more or less along the lines of the medieval German Empire. This solution struck directly at the heart of Nazi nationalism and would, Jung argued, enable Germany to break out of the diplomatic isolation in which it currently found itself. At the same time, Jung called for the creation of an elective monarchy and the appointment of an imperial regent whose sovereignty would embrace not just Germany but the territories of the Holy Roman Empire as well. Moreover, Jung stipulated, the regent could not be a member of the NSDAP.

Jung’s memorandum of April 1934 was remarkable not only for what it proposed in the way of a reorganization of the European state order but also because it was to serve as a call to action for those in Germany who were willing to take up arms against the Nazi state. To be sure, not all of those who were involved in planning a coup against Hitler agreed with Jung’s goals or ideology. In fact, very few did. What they admired in Jung was the courage he had shown in taking a stand against Hitler and his regime, but that was only one more layer of a conspiracy that was complex and could not be reduced to a common denominator beyond the need to remove Hitler and his confederates from power. Nevertheless, the action was to be triggered by a speech that Jung wrote for Papen with help from members of his staff in the Vice Chancery that was take place at the University of Marburg on June 17, 1934. Hitler was infuriated by the text of the speech and immediately ordered that any mention of it in the German press should be censured and those who were responsible should be dealt with appropriately. Jung, who was fully aware of the danger in which he found himself, was arrested in his Berlin apartment ten days later when he tried to retrieve money in the mail. Three days later he was shot in a forest outside of Berlin, a casualty of what in the history of the Third Reich has come to be known as “The Night of the Long Knives.”

Is there a connection between Jung and conservative intellectual currents in the Western world, or did he remain a purely historical figure? Can Jung’s ideas be reinterpreted in contemporary political debates?

To be honest, I find it very difficult to connect Jung’s thought to conservative intellectual currents in the Western world. His thought was very much a product of the times in which he lived, and much of what he had to say rings hollow today. This is particularly true of his evocation of the period before the Enlightenment and French Revolution as a point of reference for the development of the post-liberal world. No matter how much we might admire Jung for having had the courage of his convictions up to and including the fate he eventually suffered, his solution to the problems of the modern world remains archaic and unrealistic. Who today dreams of returning to the world before the French Revolution or using it as point of reference for the future development of the world in which we live? Who would think of turning back the clock of history two hundred or more years to solve the problem we face today. Jung is best understood as a man of the times in which he lived, as a thinker whose evocation of the past is ill-suited for solving the problems that modern society and the modern state system currently face.