When I came across this statement by Jalal Al-e Ahmad about Ernst Jünger, I was deeply moved: “Jünger and I were investigating roughly the same subject, but from two different perspectives. We were addressing the same question, but in two different languages.” Building on this statement, we explored how the two thinkers approached their shared concerns from distinct cultural and intellectual backgrounds with Alessandra Colla of Eurasia Rivista, within the framework of the conservative revolution and Gharbzadegi.

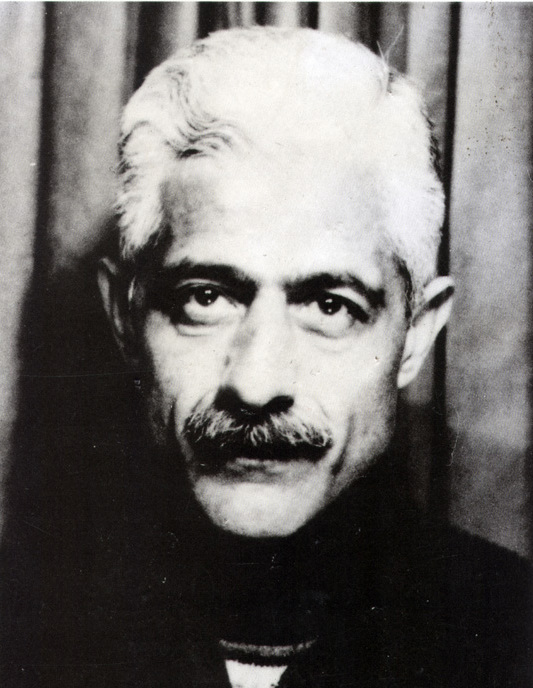

Jalal Al-e Ahmad remains a thinker whose works and concepts are still a subject of debate today. Could you tell us about his life and the transformations in his intellectual world? What factors triggered these changes?

In Italy, Jalal Al-e Ahmad is virtually unknown outside of specialist circles. Yet, this thinker is a central figure in the landscape of 20th-century Iranian intellectual history, to the point of being considered one of the inspirers of the 1979 Revolution.

His life is deeply intertwined with the troubled history of 20th-century Iran. It’s difficult to recount it fully in an interview, so I will limit myself to outlining it in broad strokes.

Born in Tehran in December 1923 to a Shiite family with a three-generation clerical tradition, he soon felt the tension between the religious worldview and the radical transformation of Iranian society under Reza Pahlavi, the Shah in power since 1925. Destined for theological studies, he abandoned them after just three months and broke off relations with his family, rejecting their religious values. In 1944, he joined the Tudeh, the Iranian communist party with a Marxist orientation (founded in 1941), and in 1946, he graduated in Persian Literature from the Tehran Teachers College, determined to dedicate himself to teaching. Meanwhile, his political career took off, leading him to become, in just a few years, a member of the Central Committee, then a delegate to the national congress, and finally director of the party’s publishing house. In this capacity, he began publishing his collections of short stories until, in 1947, he obtained his teaching qualification. In the same year, he left the Tudeh, which he criticized for its Stalinist dogmatism. His example was followed by others, and inspired by Khalil Maleki—an Iranian left-wing intellectual and politician—the dissidents founded the Iranian Workers’ Party.

But in 1948, the Tudeh experienced another split, from which the Third Force was born: a political movement for the independent development of Iran, which aimed to combine nationalism with a form of democratic socialism and Marxist centrism, thus distancing itself from both Western and Soviet influence. Al-e Ahmad joined it shortly after leaving the Iranian Workers’ Party, but the movement dissolved in 1953 with the coup—orchestrated by the United States (CIA) and Great Britain (MI6)—that returned Mohammad Reza Pahlavi to power, who had been on the throne since 1941 and was temporarily in exile in Rome. In the same year, Al-e Ahmad definitively retired from activism and, in the following decade, dedicated himself to teaching, literature (as an author and as a translator from French of works by Camus, Gide, Ionesco, and Sartre), and ethnographic research in northern Iran and the Persian Gulf. Here he discovered the world, until then unknown to him, of the rural subproletariat, rich in values he recognized as archaic yet far superior to the fictitious ones imposed by modernity. This experience profoundly affected him, contributing decisively to the last intellectual turning point of his life, as will be seen.

Until 1968, he traveled extensively (United States, USSR, Israel, Saudi Arabia), publishing accurate and critical accounts of his experiences. Of extreme importance was his trip to Mecca in 1966, after which Al-e Ahmad proclaimed a return to his roots, fully re-evaluating Islam in general and Shiism in particular, now seen as the only possible cure against the “Western infection” plaguing Iran. He wrote one last work, published posthumously in 1978: On the Service and Betrayal of the Intellectuals (Dar khedmat va khianat roshanfekran), a vehement denunciation of the disengagement of Iranian intellectuals; the reference to Julien Benda’s The Betrayal of the Intellectuals, published in 1927, is transparent.

Al-e Ahmad died in September 1969 at his home from a heart attack, but a rumor soon began to circulate (still unfounded) that he was eliminated by Savak, the Shah’s secret police.

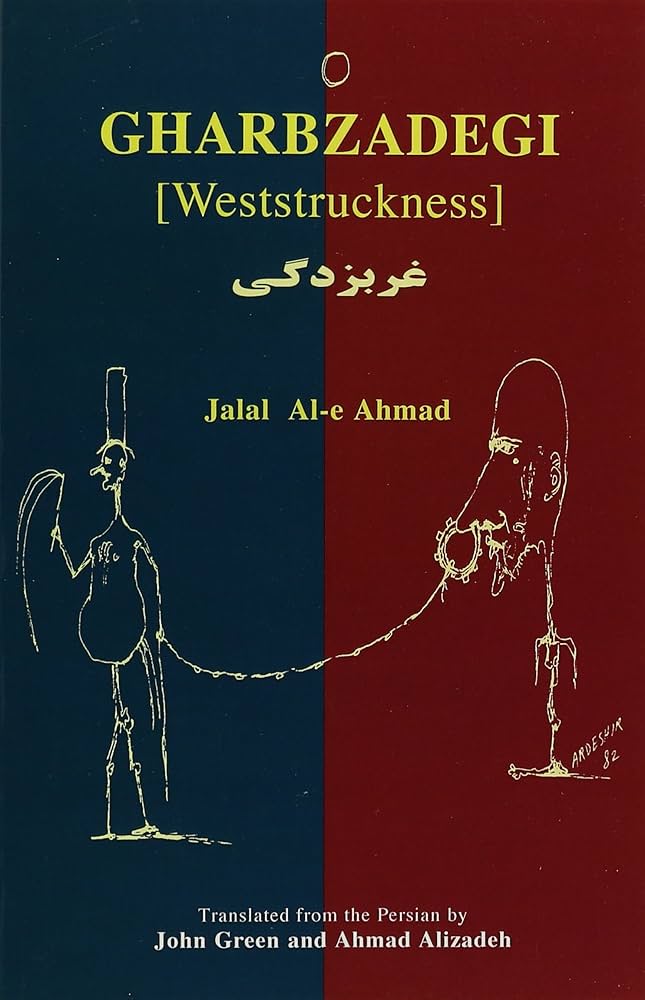

The first concept that comes to mind when thinking of Jalal Al-e Ahmad is “Occidentosis” (Gharbzadegi). Could you explain its meaning and context?

Al-e Ahmad wrote Gharbzadegi in 1961, circulating it clandestinely. The book, published in 1962, was immediately censored and withdrawn from bookstores. The title is very specific: it is generally translated as Occidentosis, which is more accurate than Occidentitis. In medicine, the suffix “-itis” indicates an inflammation affecting an organ or system, but Al-e Ahmad is not discussing the ailments of the West. On the contrary, he wants to stigmatize the West as a disease afflicting the non-West, which is why Occidentosis is a more fitting translation. In medicine, the suffix “-osis” indicates “a degenerative condition” or “a state or condition”, and indeed, the author means that Iran—and the non-Western world in general—is “ill with the West”.

It should be clarified that the term gharbzadegi is not an original coinage by Al-e Ahmad; rather, he borrowed it from the philosopher Seyed Ahmad Fardid (1909-1994), a scholar of Heidegger and considered one of the inspirers of the Islamic government that came to power in 1979. Fardid’s critique of the West operates on a strictly philosophical and specifically ontological level: he explicitly denounces the 2500-year dominance of the Western philosophical tradition over metaphysical thought, which has led to the oblivion of the intuitive and spiritual dimension in favor of pure reason detached from the truth of being.

Al-e Ahmad, however, adopted the term but gave it a different meaning. Specifically, he compared Occidentosis to a moth infestation that corrodes a Persian carpet from the inside: the form remains intact, but the substance is impoverished and emptied, rendering the carpet fragile and worthless. The West weighs on the Iranian identity not merely as political colonialism (with all its evils) but as a colonization of conquest and exploitation that destroys mentality, customs, culture, and the economy, subjugating an entire people and turning a nation into an empty shell. How was it possible to reach this point? The answer is as simple as it is painful: the responsibility lies with the Iranian ruling class—the Shah and intellectuals alike—who subserviently bent to Western “civilization”. In a useless attempt to imitate it, they accepted the destruction of local craftsmanship, cultural alienation, and the loss of traditional values. The consequence was a catastrophic, humiliating economic and technological dependence that relegated Iran to the Third World.

It is precisely this interpretation that Fardid reproached Al-e Ahmad for, accusing him of trivializing a phenomenon with a profound civilizational impact. In reality, by shifting the concept of “Occidentosis” from the plane of ontological critique to that of political and socioeconomic diagnosis, Al-e Ahmad managed to make this concept accessible to a wider audience, transforming it into a powerful anti-colonial vector capable of galvanizing dissent and significantly influencing the opposition that would later lead to the 1979 Revolution.

But Al-e Ahmad did not stop at denouncing the problem; he also suggested a solution, identifying it in a “third way” that could face technological modernity without succumbing to or denying it: Iran can and must acquire control of technology and become an active producer itself instead of a passive consumer. Naturally, this option is not without its problems: once “Occidentosis” is overcome, the greatest risk is what we might call “Machinosis”, or “machine intoxication”. For this reason, Al-e Ahmad says, it is essential to consider the machine (technology) a means and not an end: the means to safeguard the freedom and dignity of Iran and its people.

At this point, another question arises: who will be the ideal subject capable of undertaking this “third way”? Surprisingly, Al-e Ahmad identifies this subject in Twelver Shiite Islam, the only element not afflicted by “Occidentosis” and, in fact, the jealous guardian of Iranian tradition. Deeply convinced of the inadequacy of intellectuals, Al-e Ahmad believed instead that the Shiite clergy, strong in its integrity, could successfully mobilize the masses to lead them to a rediscovery of the most genuine Persian-Islamic identity.

Predictably, this stance provoked controversy and criticism at the time: beyond accusations of betrayal, it is undeniable that Al-e Ahmad’s vision of national sovereignty and self-sufficiency seemed to lack philosophical rigor and practical implementation guidelines. In fact, this unintended ambiguity would later leave the door open for the uncontrolled emergence of an Islamism and anti-imperialism that were ends in themselves and not channeled into the framework of a structured political action.

In his book Occidentosis, Jalal Al-e Ahmad quotes Ernst Jünger, saying: “Jünger and I were both exploring more or less the same subject, but from two different viewpoints. We were tackling the same question, but in two languages”. How did Ahmad and Jünger intellectually intersect? Why did Ahmad feel close to Jünger?

We know that the intellectual connection between Al-e Ahmad and Jünger was not direct but mediated through the thought of Martin Heidegger, which was in turn conveyed in Iran by Fardid. Heidegger (who even dedicated a 1939-40 seminar to Jünger) saw in Jünger the most acute critic of the modern era, the thinker who had best managed to analyze and clinically diagnose the essence of technology, albeit without grasping its metaphysical foundation. In particular, Heidegger’s attention had focused on two seminal texts by Jünger: Total Mobilization (Die totale Mobilmachung, 1930) and The Worker. Dominion and Form (Der Arbeiter. Herrschaft und Gestalt, 1932).

I will briefly recap them. For Jünger, after the radical experience of World War I, “total mobilization” no longer concerned only the economic and military spheres but enveloped the entire society, becoming the fundamental organizational principle of the modern world. In this world, all energies, resources, technologies, and human beings themselves are “mobilized”—that is, organized and framed to serve a single gigantic productive process, identical in peace and war. The Worker, in his dual dimension of laborer-soldier, embodies the new human type that emerged from the war experience as the protagonist-instrument of the will to power expressed by Technology: in peacetime, he operates the machine, just as he had served the artillery piece in war. I’ll note here that the Italian translation chose “operaio” (factory worker) for the German “Arbeiter” to immediately identify the figure working in a factory, the very symbol of industrial and capitalist modernity. I also maintain the capitalized initial because, in Jünger’s discourse, “The Worker” and “Technology” are metaphysical figures.

The study of Jünger’s texts allowed Heidegger to develop the fundamental concept of Gestell, or “Enframing”, which he identified as the essence of modern technology. The Gestell is not a single machine or apparatus but the way in which things and reality (human beings, animals, nature) are arranged in our time, stripping them of ontological meaning or value and making them a mere Bestand —a “standing-reserve” or “resource”—for the needs of technology. Thus, for example, a river or a lake is a resource for a hydroelectric power plant, a forest is a resource for the timber industry, and a human being is a resource for a company.

Like Jünger, therefore, Al-e Ahmad also identified in technology—the possession and control of the machine—the distinctive feature of modernity. This feature depersonalizes the human being, emptying him of all spirituality and opening the door to nihilism. Iran’s dependence on machines is precisely “Occidentosis”, which threatens the very existence of the individual and the people, annihilating their identity in perfect conformity with the colonialist project.

Are there parallels between the concept of “Occidentosis” and the perspective of the Conservative Revolution regarding war, technology, culture, etc.? Can we speak of an intellectual alliance in this case?

I’ll return to the phrase by Al-e Ahmad quoted above: “Jünger and I were both exploring more or less the same subject, but from two different viewpoints. We were tackling the same question, but in two languages.” Here, the expression “in two languages,” in my opinion, should be interpreted precisely as “in two different discourses.”

Between Jünger and Al-e Ahmad, there is certainly a more or less marked consonance in their perception of Technology as a destructive force. For the German, it is an autonomous, planetary entity that annihilates the individual as a person, transforming them into the Worker—a standardized, interchangeable, and faceless human type who has lost contact with nature and tradition. For the Iranian, technology is a tool of cultural and economic colonization that destroys local identities, turning people into rootless individuals who despise their own traditional culture but, at the same time, cannot integrate into the dominant Western culture.

However, the situation is different regarding their overall view of history and their proposed solutions (assuming one exists).

Jünger, as we know, is a prominent figure of the Conservative Revolution. In his elitist and anti-bourgeois vision, history is a metaphysical process of the affirmation of a will to power, which in the 20th century culminates in the dominion of Technology. Al-e Ahmad’s conception is quite different: as a Third-Worldist and anti-colonialist, he reads history as a people’s struggle for emancipation from Western domination.

From these premises, the two thinkers develop a coherent project to escape modernity. For Jünger, who holds an individualistic vision, the solution lies in what he himself calls the “Passage to the Forest” (Waldgang): an interior, aristocratic, and solitary—nihilistic—resistance that does not involve the organization of articulated movements or structures but, at most, a “recognition” among like-minded individuals, while strictly rejecting collective commitment. Al-e Ahmad, conversely, envisions precisely a collective—spiritual and identitarian—return to Shiite Islam, a central element immune to “Occidentosis” and therefore the only cultural and political bulwark against the West. These ideas, in fact, would contribute significantly to the ideological framework of the 1979 Revolution.

In light of these considerations, it seems correct to speak not so much of an “intellectual alliance” as, rather, of a “critical convergence” on the ground of the critique of modernity. For both thinkers, 20th-century Western society is an anti-model in every respect, particularly concerning Technology, which acts as a sort of metaphorical meat grinder that swallows the person with a distinct identity and returns them as an undifferentiated organic mass. But the ideological projects they champion diverge radically, also because the contexts in which they operate are radically different: both look critically at modernity and its related problems, but Jünger does so from a point of view internal to the West, while Al-e Ahmad does so from an external point of view, as a colonized person.

In conclusion, I believe we can say that Al-e Ahmad embraced this part of Jünger’s complex thought as a valuable instrument, useful for the development of a well-structured critique of modernity—with its corollaries of liberalism and rationalism—and oriented toward the recovery of the cultural authenticity of an entire people.

You also write for “Eurasia Rivista”. How is geopolitical thought developing in Italy? Which figures or currents stand out in this field? In particular, who are the most relevant names in Italian geopolitical studies in recent years?

Since the post-World War II period, Italy—unlike other countries such as France or the United Kingdom, for example—has not had a strong, autonomous academic geopolitical school. The discipline was, in fact, associated with fascism (an era in which eminent scholars like Ernesto Massi and Giorgio Roletto dedicated their attention to the Mediterranean) and was therefore stigmatized.. Even today, it is often taught as part of Political Science, International Relations, or History faculties.

In Italy, the most vibrant debate—heavily influenced by political and ideological affiliations—generally takes place outside universities, in think tanks or on magazines and newspapers. The main protagonists are very often journalists, analysts, and former diplomats.

Broadly speaking, four main currents can be identified.

The first, and dominant one, is the Atlantist-Europeanist current, aligned with Italy’s official position within NATO and the EU. It is prevalent in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, military and financial circles, and moderate center-right and center-left parties. It sees NATO as a fundamental pillar of national and European security, supports European integration, backs the transatlantic partnership, and considers cautious humanitarian or stabilization interventionism. Key institutions include the Italian Institute for International Affairs (IAI) and the Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI). Prominent names include General Carlo Jean and Andrea Margelletti, president of the Center for International Studies (CeSI) and a government consultant.

The second current is the Sovereignist/National-Conservative one. It emerged with the rise of the League (led by Matteo Salvini) and Brothers of Italy (led by Giorgia Meloni) parties, aiming to re-establish national sovereignty and Italian interests first. It criticized the bureaucratic and federalist EU, preached a strong realism in national interests, expressed concrete skepticism towards NATO as a tool of US hegemony, and declared an openness to dialogue with Russia and China. I’ve used the past tense because these ideas belong to the period when the League and Brothers of Italy were in opposition; now that they are in government, they have aligned with the mainstream, proving to be even more Atlanticist and tied to the United States and its interests, to the detriment of national interests. The key magazine is Analisi Difesa, and among the names, its director, Gianandrea Gaiani, is worth mentioning.

Then there is the current we could define as Realist (or Neo-Realist): more academic and analytical, it recognizes the substantial anarchy of the international system and examines international relations based on the balance of economic and military power. Lucidly critical of Atlanticism, it does not reject it but still advocates for the primacy of national interests. It harbors a certain skepticism towards humanitarian interventions and believes it is necessary for Italy to adopt a long-term “grand strategy” (a goal, in my opinion, unachievable as long as Italy remains under the NATO/EU umbrella). The reference magazine is the authoritative Limes, founded and directed by Lucio Caracciolo; other notable names are Dario Fabbri and Giulio Sapelli.

Fourth is the current we could call Third-Worldist/Anti-Imperialist and Anti-Colonialist, rooted in the communist and anti-American left. It is strongly critical of Western hegemony and of NATO as an aggressive tool of the United States; it supports national liberation movements and the Palestinian cause. Its main representatives are Manlio Dinucci and Alberto Negri: the first is a journalist for the newspaper il Manifesto, and the second is a contributor.

Finally, the magazine “Eurasia” represents a reality of its own, difficult to label ideologically today. As we have seen, its explicitly anti-Atlanticist, anti-globalist, anti-colonialist, and anti-Zionist stance is shared by other geopolitical currents. Another of its strengths is the attention it gives to the Global South and, today, to the BRICS, with a focus on the Middle East (primarily the Palestinian question) and Central Asia.

Founded in 2004 by Claudio Mutti and Carlo Terracciano (one of the first and sharpest post-war geopolitics scholars of the 20th century, who passed away prematurely exactly twenty years ago, in September 2005), Eurasia aims both to promote academic-level geopolitical studies and research and to raise awareness among the public (both specialist and non-specialist) about Eurasian themes: where “Eurasia” is understood as the Eurasian continent from Greenland (in the west) to Japan (in the east).The rediscovery of the spiritual unity of Eurasia—as it has expressed itself over time in multiple cultural forms—not only represents an innovative factor in the landscape of geopolitical studies but also constitutes a valid alternative to the now-obsolete theories of the “end of history” and the “clash of civilizations” developed respectively by Francis Fukuyama and Samuel Huntington at the end of the 20th century. Although a niche publication, Eurasia can count on a loyal audience and a circle of qualified contributors.