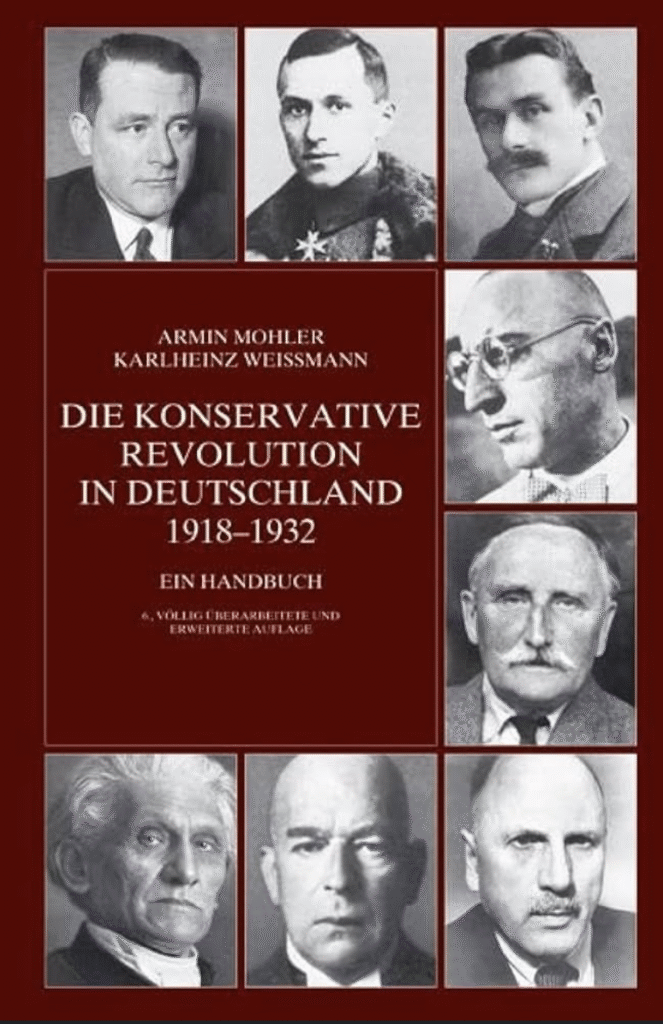

When Armin Mohler wrote his book, The Conservative Revolution in Germany 1918–1932, he left behind a significant legacy that would be debated for a long time. Mohler, who once served as Ernst Jünger’s secretary, is one of the key figures of conservative revolutionism.We discussed Mohler with Robert Steuckers, a leading figure of the European New Right and the founder of the Synergies européennes movement.

Could you tell us about Armin Mohler and his book The Conservative Revolution in Germany 1918–1932? By using the still controversial concept of a “conservative revolution,” what exactly did he mean and what framework of thought was he trying to construct?

I first came into contact with Armin Mohler primarily through phone conversations, mostly in the context of the Munich-based journal Criticon, which was directed by Baron Caspar von Schrenck-Notzing. In 1978-79, for the GRECE-Brussels journal led by Georges Hupin, I summarized the famous debate between Armin Mohler and Thomas Molnar, a Catholic and Aristotelian-Thomist philosopher. This debate concerned the dispute of the universals: Molnar defended universals in the Thomist tradition, which he believed needed to be restored to their fullness to halt decadence. Mohler, on the other hand, felt that universals had degenerated into generalizing platitudes that no longer allowed for any political dynamism. He presented himself, perhaps a bit clumsily, as a “nominalist” attentive to all particularities—national or vernacular—in opposition to the “generalities” (die All-Gemeinheiten, as he called them) of Western liberal ideology. Molnar believed that this liberalism had dissolved all the solid foundations of communal living to promote “occasionalist” (Carl Schmitt) individualisms. This summary, put on paper by an obscure young student from Brussels, kicked off a whole debate within the French-speaking “new right” circles, a debate that has since faded over the decades, as this milieu, primarily Parisian, has now forgotten Mohler’s work, which went far beyond the themes of the Conservative Revolution.

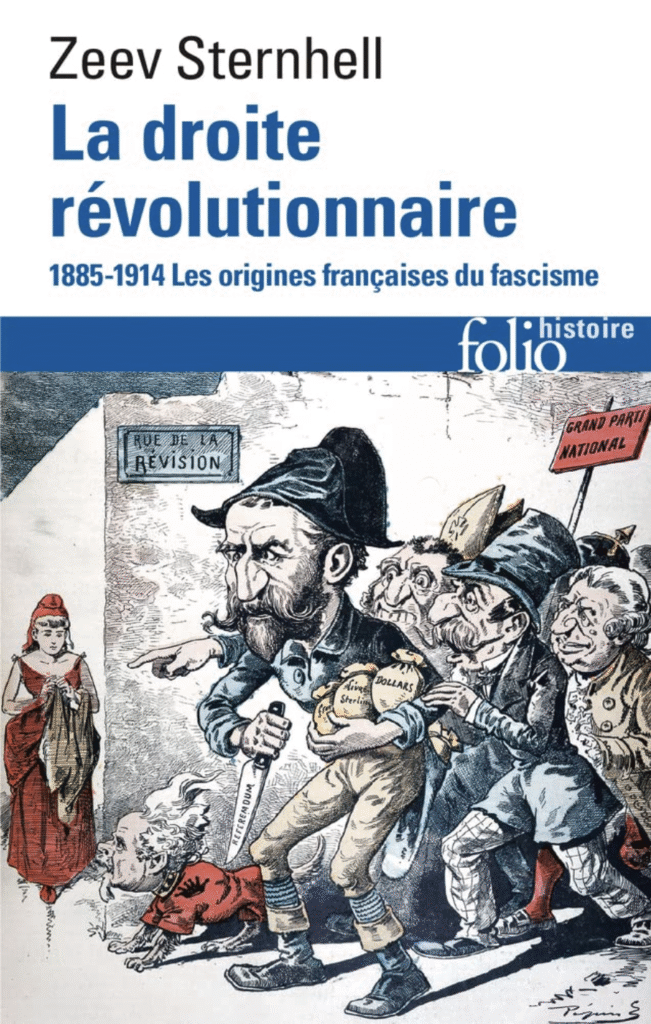

Later, Mohler became interested in the didactic work of the Israeli historian Zeev Sternhell on “The Revolutionary Right” in France, which emerged after the defeat of Napoleon III’s armies in 1871 and was obsessed with the desire for revenge. This period, notably marked by the adventure of General Boulanger, who concocted a military and popular coup d’état, had also interested Ernst Jünger during the hottest years of the Weimar Republic. Jünger believed that a forceful takeover, like Boulanger’s, was a “cleaner,” “nobler” way to seize power than the corruption of a party-based democracy, such as the one that came to power after the November 1918 events. Mohler therefore wrote a particularly didactic summary of Sternhell’s book, La droite révolutionnaire, for the journal Criticon. Elfrieda Popelier, who was then involved in the activities of GRECE-Brussels, undertook the translation of this text, and I decided to publish it in Geneva as a substantial brochure, accompanied by a text by the Marseilles jurist Thierry Mudry (on certain interesting aspects of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s work, as seen by Noel O’Sullivan) and my own comments on Sternhell’s work. These comments were, by the way, derived from the script of a lecture I gave in Cologne at the Gesamtdeutscher Studentenverband (GDS) at the initiative of two now-deceased friends, Günter Maschke and Peter Bossdorf. This work was quite successful and had numerous re-editions.

At the time, the book Die Konservative Revolution in Deutschland 1918-1932 was almost impossible to find and had not been re-issued. It was not until 1988-89 that the publisher “Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft” produced a new edition, which I in turn summarized, this time for my own journal, Vouloir. The leader of the Antwerp journal Tekos also reviewed the work, adding comparative notes between the German conservative revolation authors and the Flemish and Dutch authors who were close to or inspired by them. I also translated this copious review and supplemented it with an apparatus of notes for French-speaking readers.

To restore the context in which this very important work on the conservative revolation emerged, let’s say that when Mohler was Ernst Jünger’s secretary, starting in 1949—the year the two German republics and NATO were created—the two men had to debate the fertile ideas and thoughts that Germany had generated over the decades, at least since the constitution of Bismarck’s Second Reich. The defeat of 1945 seemed to render any restoration project based on such ideas, and especially those that had animated all the debates between 1918 and Hitler’s rise to power, obsolete. It was therefore necessary to take an inventory of all these ideas so that a trace would remain, with the hope that bold new minds would seize them, update them, and translate them into a new reality after a possible collapse of the system put in place by the American services.

In the scattered and fragmentary notes of his journal from the time he was Ernst Jünger’s secretary (cf. AM, Ravensburger Tagebuch – Meine Jahre mit Ernst Jünger, Karolinger Verlag, Vienna, 1999), Mohler explains, very succinctly, how the idea for this doctoral thesis came to him. When he applied to take on the role of Ernst Jünger’s secretary, Mohler received this injunction from him: “I insist that you first finish your studies.” Ernst Jünger did not want to take advantage of a naive idealist who would sacrifice his future to devote himself to his person alone. A wisdom that many others in the vast conservative-revolutionary or neo-rightist movement would not later retain. Armin Mohler then asked the quiet philosopher Karl Jaspers to sponsor his doctoral thesis. Jaspers accepted, even though Mohler had initiated a polemic against him within the text of his thesis. Jaspers then asked him: “Is it true that on a certain page you are polemicizing against me?” Mohler confirmed, and Jaspers replied: “We philosophers often harbor snakes in our bosoms, but I presume you will not make much use of philosophy later…” Mohler then asked Jünger why he had attached so much importance to the writing of this thesis. The answer: “No importance, but I did not want to be responsible for the fact that you would not have had a doctorate.”

At the time, Ernst Jünger had abandoned the radicalism of his political-philosophical theses of the 1920s and 1930s (at least until 1934). From the ideological hardness of the national-revolutionary and the “soldierly” writer, he had moved on to meditation, slipping toward traditionalist positions that would be expressed in an extraordinary journal, Antaios, which has since had no equivalent in the German linguistic space. Mohler, being younger, recalled that during his escape from Switzerland (he was a native of Basel) from January to December 1942, he had forced himself to copy by hand all of Jünger’s national-revolutionary articles in the libraries of Berlin. The young Mohler’s reference book was The Worker (Der Arbeiter). He wanted to rediscover this rebellious and exalted spirit, hostile to liberal systems, in his boss (Der Chef). The latter had just completed another great book, Heliopolis. Mohler considered this work “inessential,” compared to The Worker, Jünger’s main book in the 1930s. Mohler therefore kept the main lines of the national-revolutionary Jünger in mind and considered the ideas developed from the publication of Heliopolis to be secondary.

In Jaspers, despite the criticisms he leveled at this good Protestant philosopher, Mohler nonetheless detected one essential idea: that of “axial periods” that punctuated and marked history. In these axial periods, earth-shattering ideas emerge and alter the peaceful trajectory of civilizations that, just before their emergence, had ossified and risked irreversible decline. For Jaspers, Buddha, Socrates, and Christ had brought the necessary earth-shattering ideas, respectively in ancient India, Greek civilization, and the Roman Empire. For Mohler, the idea of an axial period could be applied to our own civilizational space, especially since Nietzsche’s desire to “revalue all values” (Umwertung aller Werte). The German Conservative Revolution holds within itself all the possibilities to transcend the political frameworks established since the Enlightenment and the French Revolution. Later, Sternhell demonstrated, according to Mohler, that the French “right-wing revolutionaries,” particularly Jules Soury, Hippolyte Taine, and Maurice Barrès (a favorite of the national-revolutionary Jünger), cultivated in the texts they wrote all the ingredients to shake up and defeat the bourgeois ideology of the Third Republic, which was inaugurated after the defeat of 1871.

For practical reasons and due to the impossibility of being totally exhaustive, Mohler’s doctoral thesis had to reduce the space-time of its investigations to the period from the collapse of the Wilhelminian Reich in 1918 to the rise to power of the National Socialists in January 1933. The ideas debated between November 1918 and January 1933, however, did not suddenly fall from the sky and have a genealogy, sometimes going back to the “other Enlightenments,” notably to the work of Johann Gottfried Herder, or even to that of Hamann in the 18th century. This is why he praised Sternhell’s work on The Revolutionary Right, because it studied a period that was particularly fertile for its criticisms of liberalism and the All-Gemeinheiten, the ossifying generalities it had generated in the Western space (and to a much lesser extent in Russia, where the critique of Occidentalism implicitly joined the works of the French right-wing revolutionaries and, later, the German conservative-revolutionaries and national-revolutionaries of the Weimar Republic, where Arthur Moeller van den Bruck was the notable translator of Dostoevsky into German).

The break between Jünger and Mohler in 1953 was caused by Jünger’s self-censorship of some of his texts from the 1920s and 1930s. Mohler wanted them to be re-issued in their entirety and without any excisions. On this subject, Mohler declared: “I had publicly protested against this self-mutilation that Jünger had inflicted on himself by censoring his youthful writings. For the Master, it was one lesson too many from his secretary.”

Note then, among many other tasks and missions, Mohler became in 1961 the secretary of the Carl von Siemens Stiftung in Munich, and would remain so until 1985. In this capacity, he sponsored collective works that, for me, were decisive in the development of my own metapolitical vision, especially the one entitled Der Ernstfall. Then Kursbuch der Weltanschauung and Der Mensch und seine Sprache (in the context of my own university studies); finally, Die deutsche Neurose (on Germany after 1945).

Politically, Mohler was clearly engaged and did not engage in “armchair metapolitics” like some of his pseudo-admirers who quote him but do not follow his instructions. Thus, with Franz Schönhuber (leader of the Republikaner), Hellmut Diwald (a renowned historian who did not hesitate to trigger formidable controversies), and Hans-Joachim Arndt (a sharp critic of Americanized political science), he founded a “Deutschlandrat“ (a “German Council”) in Bad Homburg, before supporting Schönhuber’s Republikaner by writing a large part of their manifesto, the Siegburger Manifest (1985).

Within this movement itself, into what distinct currents or tendencies were the “conservative revolutionaries” divided?

The main currents that should be remembered today because they still have some relevance for current debates are the “National-Revolutionaries,” the “Völkisch” (folkist) current, and the “Jungkonservative” (Young Conservatives). I would personally count the Schleswig-Holstein “peasant movement” among the National-Revolutionaries because it had the clear support of the Jünger brothers and Ernst Niekisch. Then, some non-directly political veins, in archaeology, linguistics, and philology, were first ousted from debates after 1945 and until the early years of the 21st century, only to return with a vengeance as research, especially in prehistoric or protohistoric archaeology, revealed their validity thanks to new techniques!

From the “National-Revolutionary” vein, admirers and detractors alike essentially remember the excesses (the ones Jünger wanted to erase in 1953). The language adopted was certainly rough, but our recent era, especially since the Maidan in Kiev in 2014 and the development of the BRICS group of countries, could discover the roots of many contemporary problems in it. The National-Revolutionaries of the Weimar Republic era envisioned Germany’s foreign policy in a way very different from that of the liberals, Christian Democrats, and socialists subservient to the major parties of the time. For them, Germany was not a “Western country”; the West, in their eyes, was limited to England, because of its deep state’s Puritan and Cromwellian foundations; to France, with its aggressive and rabid, sterilizing republican ideological hodgepodge that squeezed defeated Germany by demanding insane reparations; and finally, the United States with its Wilsonian practice in foreign policy and its desire to bring Germany under its control by offering financing and recovery plans (the Young and Dawes plans), accepted by a short-sighted German bourgeoisie. This American policy would be perpetuated by the Marshall Plan after 1945 and by the current takeover by BlackRock under the aegis of the new Chancellor Merz.

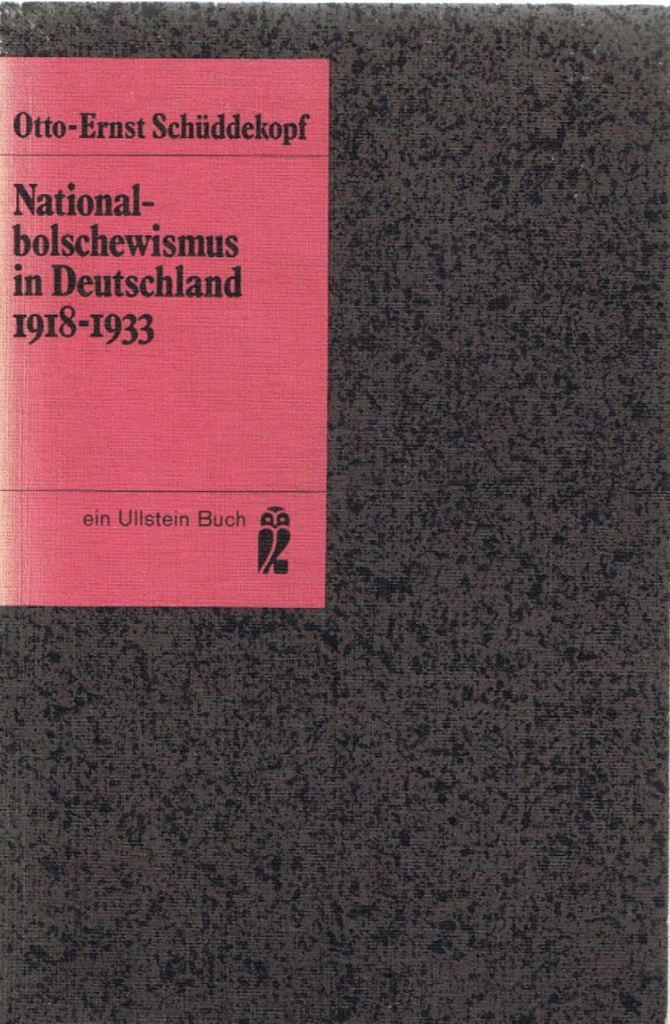

The German National-Revolutionaries of the 1920s and 1930s envisioned, to get out of the vice imposed by the Western trio, uniting Germany’s forces with those of the young Soviet Union (in which they saw a new avatar of eternal Russia), with Kuomintang China (supported by German military advisers, including General Hans von Seekt). They evoked a “German-Russo-Chinese Triad,” which would be quickly joined by an India freed from the British yoke, a Persia regenerated by Shah Pahlavi, Kemalist Turkey, and Arab independence fighters (especially Iraqi and Syrian). This was, in fact, the policy advocated by Primakov before his time! The quarrels between the Soviets and the Chinese, after the anti-communist repression led by the Kuomintang, meant that the Soviet Union no longer considered any participation in a potential “Triad” as long as the nationalist Chinese were part of it. Hitler’s seizure of power further reduced the possibility of such an Eurasian Triplice. The reflections and actions undertaken to bring about such a “Triad” were thoroughly studied by a student who used to attend the lectures of Jünger, Niekisch, Fischer, and Paetel. His name was Otto-Ernst Schüddekopf (1912-1984). He wrote a copious work on this subject, which the self-proclaimed “National-Revolutionaries” or “neo-rightists” of Paris and elsewhere never quote, do not know, and do not want to know: Nationalbolschewismus in Deutschland 1918-1933 (Ullstein, 1960-72). The refusal of any subordination to the Western trio is an idea that Mohler would translate and update in his Chicago Papers (written in English). This short text, in the form of a series of brief directives, should constitute the breviary of any European wishing to protect his country from the nuisances spread by London, Washington, and Paris (unless Paris returns to the Gaullist policy of independence of the 1960s that Mohler admired).

The “Völkisch” movement has only recently been scientifically studied. It was born immediately after the proclamation of the German Empire in 1871. This proclamation led to France paying considerable war damages, 5 billion gold francs. This influx of poorly managed capital led to a financial crisis in 1873, which greatly displeased the less wealthy middle classes and within which ideological alternatives mixing nationalism and socialism were born, albeit in heterogeneous forms, always mixed with other non-political veins such as the youth emancipation movement, neo-ruralism, ecology before its time, and “life reform” movements (nudism, vegetarianism, animalism, anti-alcoholism, etc.). The völkisch movement did not manage to create a political “pillar” comparable to social democracy or Christian democracy (Zentrum) or some liberal parties (liberalism also being heterogeneous at the time). The rejection of the system that nevertheless served as a common denominator for all völkisch initiatives between 1871 and 1914 is found today in the populist movements that are establishing themselves all over Europe, also due to a financial crisis with unresolved effects, that of 2008. And to this financial crisis are added other crises: moral, political, migratory, etc. The study of the völkisch movement as a protest against the system in place is therefore useful for understanding our own time.

You personally met Mohler. What do you remember about him? What relationship did you perceive between his intellectual personality and his individual character?

My relationship with Mohler was mainly over the phone, as I have just said. The first contact took place when I was working in Paris at the editorial office of Nouvelle école, between March and December 1981: we got to know each other and, the next time, discussed a new collection of books, the “blue series” published by the Herbig publishing house in Munich with the aim of spreading unusual and non-conformist national-revolutionary theses (with a book by the theorist Henning Eichberg and the summary of a doctoral thesis on Niekisch by Uwe Sauermann). The same year, in the autumn, Mohler gave a talk at Laarne Castle in Flanders at a symposium organized by the journal Tekos: it was our first in-person meeting. To note: among the participants in this study day was Edgard Delvo, former secretary of the socialist theorist and Belgian minister Henri de Man, a theorist of planism who would influence Gaullism through one of his disciples, André Philip (who, for his part, did not opt for a truce with the German power of the time).

In 1983, Mohler was in Paris for a GRECE symposium. In July 1984, I visited Armin Mohler at his home in Munich. I met his wife Edith, who always supported her husband’s initiatives with fidelity and selflessness. She was also the incarnation of the most perfect kindness. On that day, it was a torrid heat, and we were all bothered by this heatwave, which, alas, did not encourage long conversations. We were all dejected, without energy. The apartment was overflowing with books, especially art books, because, in addition to his constant interest in politics and metapolitics, Armin Mohler was also a very sharp art historian and a specialist in the avant-gardes and their revolutionary messages, both on the politico-ideological and aesthetic levels. It is impossible to understand 20th-century ideologies without taking into account the impulses given at regular intervals by the artistic avant-gardes. This is true for Germany with expressionism, for France with surrealism and its multiple avatars, for Belgium and the Flemish movement with Wies Moens, Paul Van Ostaijen, Michel Seuphor, and Marc Eemans. The primary political commitment of these avant-gardists was very often communist, but their subsequent evolution led them to other, varied, and different horizons, but always in break with the conformism of their contemporaries and especially with the political platitudes of the dominant parties. Exactly like the young student Mohler, who was on the left at the beginning of his metapolitical gropings, and on the muscular right for the rest of his ideological trajectory.

On that scorching day in July 1984, Mohler took me to the raised basement of his building where he had stored the finest jewels of his library: original, dedicated, and/or very rare copies. For Mohler was also a meticulous collector.

As for his intellectual personality, I would say that he was rigorous in his research but always didactic in his explanations or in his injunctions to act, and he consistently handled a powerful style. His concern was to make vocations emerge, to lead people to discover the essential in subversive or radical texts to germinate a new revolution. He certainly had a very precise knowledge of the ideological past of the Germanic cultural area, but he did not get bogged down in a specific past, whatever it might be. I had the opportunity to answer a questionnaire once submitted to me by Marc Lüdders, on the paths that Mohler suggested to us in the columns of Criticon, Caspar von Schrenck-Notzing’s journal. None of these paths referred to facts, personalities, or events of the past, apart from the reference to Georges Sorel, an author he considered essential, as the obligatory reference: one can say that Mohler was even more Sorelian than “conservative-revolutionary” (the term “conservative,” even if he sometimes used it excessively, did not really suit him at heart). I give you these answers to Lüdders in the appendix to this interview.

Mohler was attentive to current ideas, in which he saw, often despite appearances, a continuation of the Jüngerian conservative revolution. This is especially true in the definition he gave, with Wolfgang Welsch, of postmodernity. Postmodernism has become the current decaying ideology that flanks the practice of neoliberalism in the West. For Welsch and for Mohler, postmodernity should have become a current hostile to the ossification of liberalism derived from the Enlightenment (and from Cartesianism, which the surrealists also wanted!). Today, without, it seems, ever having consulted Mohler and Welsch, Alexander Dugin agrees in the same vein: we must create, he teaches us, a posterity for modernity that is not the official postmodernism, approved by the system in place today, because this system has produced the cultural and political mess in which the entire West, the entire American sphere, is bathed. With, as the icing on the cake,

As for Mohler’s character traits, I would say that he was above all a gourmet (and a glutton), a lover of good French food, good wines from the Burgundy or Bordeaux terroir, and, as I have already said, a zealous collector of everything related to the numerous subjects he tackled.

Did the fact that Mohler was Ernst Jünger’s secretary influence his intellectual journey? What was his relationship with Jünger, but also with other figures of the Conservative Revolution?

The years spent with Jünger, between 1949 and 1953, certainly had a dominant influence on Mohler, although his basic ideas had already been developed before his arrival at Jünger’s new home in Ravensburg near Lake Constance (Bodensee), on whose shores Friedrich-Georg Jünger also lived. As I have already said here, Mohler wanted to resurrect the national-revolutionary movement of the 1920s and 1930s, to develop a critique of the new Federal Republic that would be as virulent as the national-revolutionary critiques against the Weimar Republic, in order to eventually bring down a regime granted by the Americans, just as the national-revolutionaries before the National Socialist era wanted to destroy a rickety regime, delivered to the French, who demanded reparations, and to the Americans, who seized the levers of the German economy and criminalized, in the name of Wilson’s principles, any assertion of sovereignty or independence (but it was Japan that was the first victim after its takeover of Manchuria).

Mohler was undoubtedly a reader of Carl Schmitt and had adopted principles such as the “great space” (European), the prohibition for any power outside my space to intervene in this my space (i.e., prohibition of any American interference in Europe or Asia), the primacy of the decision in the political process, the importance of the state of exception in a country’s history, etc. However, he once had the opportunity to say that the Catholic system in which Carl Schmitt always navigated was foreign to him, just as Thomas Molnar’s Aristotelian-Thomist system was foreign to him when he polemicized with him in the columns of the journal Criticon. Mohler is a “nominalist” (although the choice of the term is unfortunate), that is, a heroic existentialist, insofar as, beyond all the substantial certainties to which Catholics cling, Mohler thinks that the will of a charismatic leader or a vigorous elite can change the course of history: his vision of history is neither linear nor cyclical. He does not believe in an inexorable progress marching towards the future by denying or forgetting all the legacies of the past. Such a forward march is never sustainable and, at one point or another, sinks into stagnation and decline. He does not believe in the regular return of the same, either. His vision of history is spherical: the sphere of time turns on itself, and the charismatic leader or the vigorous elite can, through will and the simple exercise of his power, impulse the rotation of the sphere in the direction of his choice. And thus open a new period in the history of a political, national, or civilizational whole. By founding new values or by revaluing the tired values of the previous era. In short, it is the manifestation of a new “axial period” that begins thus. There are therefore no eternal universals, no perennial generalities. Mohler, here, is Nietzschean: “Amor fati.”

How was the Conservative Revolution movement received outside Germany? What exchanges did it have with currents in France and Italy? In your opinion, does a movement that can be qualified as “Conservative Revolution” still exist today?

To try to grasp the impact of the conservative revolation outside Germany, one must first know that the German language was more known and practiced (at least through reading) before 1940 in the Scandinavian, Dutch/Flemish, Swiss, Hungarian, Czech, Polish, Croatian, or Slovenian periphery than it is today, where everything has shifted to English. Similarly in Italy, the interest in German ideas was real before 1940 and, today, this interest is still more evident in the Italian peninsula than elsewhere in Europe. I do think, however, that the great figures of the German Conservative Revolution have become classics throughout the world: one only has to consider your own work and know that Carl Schmitt’s texts are now unavoidable references in Xi Jinping’s new China. Mohler once said that four-fifths of the authors he cited in his thesis on the Conservative Revolution are forgotten or no longer have any relevance today. This is true. But the great classics are more important than ever in fundamental debates: Jünger, Spengler, Schmitt, Haushofer are essential thinkers and have retained all their virulence when it comes to contesting the system. They belonged to the camp of the defeated, but the victors have not been able to keep the system they put in place in good working order. This system is sinking, taking on water from all sides, especially since the 2008 crisis. The remedies of the quartet I have just cited are the recipes that are suitable for remedying the failures of liberal Americanism and for moving on to a real postmodernity, such as Mohler and Welsch envisioned and as Dugin envisions today.

Mohler was a correspondent for several German and German-Swiss newspapers in France from 1953. He would remain in Paris for four or five years. He made an assessment of his subsequent observation of Gaullism in 1963, the year Franco-German reconciliation began with the De Gaulle-Adenauer meeting in Colombey-les-deux-Eglises, the French President’s secondary residence. Mohler would write a second doctoral thesis on De Gaulle’s France, which allowed him to write a remarkable book for the general public in which he welcomed the spirit of independence and sovereignty of France in the 1960s, after the turmoil and upheavals of the Algerian conflict (cf. Die Fünfte Republik. Was steht hinter de Gaulle?, Piper, Munich, 1963). Mohler bet on a Gaullist France at a time in France’s recent history when the right was nevertheless very hostile to the president and when nationalist militancy had taken the form of the OAS (Organisation de l’Armée Secrète), a clandestine organization that had organized numerous attacks in Algeria and metropolitan France and then tried to assassinate De Gaulle. Many leaders of the “new right” came from the OAS or the movement that sympathized with this organization. Mohler was therefore at odds with them. From Jünger, he inherited a systematic rejection of attacks targeting prominent political figures. Jünger had advised against the attack on Rathenau (in which Ernst von Salomon had participated) and had deemed dangerous the one orchestrated by Claus von Stauffenberg (whose family he was close to) against Hitler. Mohler therefore disapproved of the attack on De Gaulle according to the same logic.

In Italy, unfortunately, the ties between Mohler and the innumerable Italian personalities who could have been on the same wavelength as him seem to me to have been very tenuous, if not non-existent. This is a shame because the ground seems more fertile in Italy than in France, where the double blanket of Jacobinism and wild leftism is much heavier and where, today, a repression much more insidious than anywhere else in Europe is falling on non-conformism, which is in the process of reorganization and is in a counter-offensive phase.

To what extent has the intellectual line drawn by Mohler influenced contemporary right-wing thought?

Recently, a German friend told me he was skeptical about Mohler’s posterity: with a lot of sadness in his voice, he lamented that this political polemicist was well forgotten in our era of intellectual decline, the collapse of school systems, and ubiquitous wokeism. This is partially true, with the exception of the small group gathered around the journal Sezession, directed by Götz Kubitschek (who had delivered a eulogy at the edge of Mohler’s grave at his funeral) and his wife Ellen Kositza, with the precious help of Dr. Lehnert. This team has published collections of Mohler’s unpublished texts or out-of-print works, which are very valuable for knowing his biography and the Swiss and German context in which his actions emerged. There are certainly links between this Sezession team and certain elements of the AfD, but these links are, as usual, subject to the vagaries and shocks of an exhausting political life and are burdened by the constant opprobrium orchestrated by the “old parties” and the hysterical thugs of the German and foreign media landscape.

To extract the remedies for a possible political renewal inspired by Mohler and the conservative revolation authors he studied, it would be necessary, in my opinion, to reread his book on France in the 1960s in a critical (in the Greek and philosophical sense of the term) manner, where a singular figure (in this case, that of De Gaulle) determined the way forward rather than parliaments composed of half-wits, bar-room clowns, crooked lawyers, or unhinged characters. Around such a personality, mixed teams (made up of non-conformists from the right and the left), exposed to all ideological debates, capable of weighing the pros and cons, should be established to inject a new sap into societies shaken by the incompetence of the “liberals” (in the sense of Mohler and the usual vocabulary of Anglo-Saxon countries). De Gaulle, moreover, wanted another representation than that of a parliament of deputies from incoherent parties: he suggested a Senate of professions and regions, with representatives from the real world, from the concrete people.

Even more importantly, we would have to meditate on and internalize the content of the Chicago Papers, reproduced in his volume Von Rechts gesehen (“Seen from the Right”). Even after 52 years of activities within the European “new rights,” but especially the French-speaking ones, I am astonished to note that these Chicago Papers do not constitute or no longer constitute the basic ABC of metapolitical and political rights in terms of foreign policy or European policy. They have never been translated and disseminated in French, Italian, or Spanish. The so-called “Mohlerians” of the “new right” (especially the Parisian one) have systematically ignored them: one can understand that they sulked at the book on France in the 1960s, given the events in Algeria and the activities of the OAS. But, as soon as the anti-American option appeared with the publication of the issue of Nouvelle école on America in 1975 (the writing of which came mainly from the Italian philosopher Giorgio Locchi) and the issue of Éléments entitled “To end with Western civilization” (written under the impulse of Guillaume Faye), the Chicago Papers should have served as a compass for all activists engaged in this metapolitical struggle or in other activities of the same ilk. It is a very short text, the content of which is easy to assimilate. It makes it possible to sort the wheat from the chaff, to never again be fooled by the false “propaganda truths” hammered out all day long within the American sphere and in the official media.

For Mohler, Gaullism went through four phases, the last of which is the most interesting, the most fertile for the future: the phase of “Grand Politics,” with an alternative global geopolitics articulated notably during the Phnom Penh speech of 1966, a period when France tried to free itself from the American vice by leaving NATO command, not hesitating to form alliances with states deemed “rogue” (China, for example), and assuming an independent policy throughout the world, which consisted of selling, for example, Dassault Mirage aircraft to Australia and South America, in direct competition with American producers of fighter-bombers. This “Grand Politics” broke in May 1968, when “anarchy” manifested itself and began its “long march through the institutions,” which led France straight to the big festive farce of the time of Sarközy and Hollande, to total decay and delirious wokeism under Macron. May 1968 was indeed a “color revolution” before its time.

Mohler, not as a reader of Jünger but as a reader of Schmitt, is a Gaullist, in the very name of the principles of his conservative revolation . He does not understand how one can fail to judge De Gaulle only on Schmittian criteria. He comments on the adventure of the OAS ultras in two lines. Mohler therefore belonged to a different political breeding ground than the future leaders of the “new right” (ND). The new German rights have other idiosyncrasies: the convergence between Mohler and the French ND (with the Jüngerian Dominique Venner) would come later when the cleavages of the Algerian war no longer had direct political relevance.

Mohler wanted to transpose Gaullian independentism to Germany. In February 1968, he went to Chicago to defend the point of view of Gaullian “Grand Politics” at a “Euro-American Colloquium.” The text of his intervention, which was written in English and was never translated into French (!), has the merit of being programmatically clear: he wanted, under the colors of a new European Gaullism, to free Europe from the straitjacket of Yalta, without, however, poisoning relations with the USSR.

The Chicago Papers therefore ask to dialogue with the states that the Americans designate as “Rogue States.” One will deduce, in the current context, that any state designated by Washington as such should be considered a potential ally or a valid commercial partner. Any war or any boycott or any policy of sanctions against such states must be rejected. In the present situation, where the states of the BRICS group or emerging states like Indonesia or even Mexico have the wind in their sails to affirm their full sovereignty, the interest of all European states is to maintain positive relations with them. Conversely, what is praised as positive by the United States should automatically trigger a reflex of profound distrust. Thus, all the exhortations of a Bernard-Henri Lévy should lead all European states to adopt diametrically opposed policies. We should do exactly the opposite of what Lévy advocates.

The last wave of reminiscence of this Gaullian “grand politics” manifested itself in the common hostility of Chirac’s France, Schröder’s Germany, and Putin’s Russia to the Anglo-American operations in Iraq in 2003. The Paris-Berlin-Moscow Axis would have pleased Mohler and sparked some hope in the very year of his death. This Axis also pleased Jean Parvulesco, Dugin’s inspirer and another propagandist of De Gaulle’s “grand politics.”

How should one interpret the legacy of Mohler—and more broadly of the Conservative Revolution—in the context of current geopolitical crises (the war in Ukraine, Sino-American rivalry, debates on Europe’s strategic independence)?

Mohler’s practical legacy lies in those Chicago Papers that I have just mentioned. In 1980, in the columns of Criticon, Mohler presented two authors who had been forgotten until then, who were also being rediscovered at the scientific level at the same time, and who, a few months earlier, would not have had their place in a journal labeled “conservative”: Ernst Niekisch, the National-Bolshevik activist, and Karl Haushofer, the geographer who committed suicide in 1946. I was still a student, finishing my studies, and the academic work to be completed was piling up on my desk, but I immediately translated them for the GRECE-Brussels bulletin. Niekisch and Haushofer would be guiding authors for me throughout my life, thanks to Mohler. Of course, even today, these authors constitute essential references in many Italian metapolitical and geopolitical circles, in Russia in the wake of Dugin, or even in Chinese offices where the policy of Xi Jinping’s new China is being shaped.

During Mohler’s lifetime, there was no Ukrainian crisis. It was a year after his death, in 2004, that the first troubles broke out in Kyiv, with the “Orange Revolution.” To intelligently understand the events in Ukraine, Crimea, and Donbass, the most interesting geographer to study remains Richard Henning (1874-1951), author of a very copious work, Geopolitik – Die Lehre vom Staat als Lebewesen. Henning developed a Verkehrgeographie, a geography of terrestrial communication axes, which is extremely interesting at a time when China intends to pursue its “Belt and Road Initiative” project and where other continental projects are being considered, such as the INSTC between Bombay and the Baltic via the Caucasus, as well as alternative projects imagined by Anglo-Saxon thalassocratic powers, such as the corridor that is supposed to lead to the Israeli coasts or even at the level of the ruins of Gaza, a city eradicated to carry out this project in appearance. The Zangezur corridor or “Trump corridor” is another very recent Western initiative, but it too, whatever one may say, falls within the logic of the organization of territories and continental communications. Mohler did not, apparently, study Henning’s works. The latter was not politicized, although he was a Clausewitzian patriot (si vis pacem, para bellum), but he nevertheless had to give up his chair in Germany, as geopolitics was no longer in good odor under the American occupation (which is still ongoing). However, he brilliantly continued his career in Argentina and was the driving force behind major infrastructure works in South America.

The Sino-American rivalry is mentioned in the Chicago Papers, since Mao’s China is presented as a “Rogue State” that the Americans want to isolate from the rest of the world. But that was before Kissinger’s diplomacy settled the Beijing-Washington dispute to the advantage of both parties in 1972. China, as if by a magic wand, was no longer a “Rogue State” but a sympathetic interlocutor, mobilizable against the “nasty Russians.” Today, both Russia and China are considered enemy states.

As for the debates on Europe’s military, diplomatic, energy, and strategic independence, they are currently non-existent or pushed back into the obscure margins where relevant but little-known authors discuss, more or less banned from airtime, television, or publishing. The debates were more visible in the 1980s when Gorbachev announced his perestroika and his glasnost. Then when he started talking about a “Common House.” In Germany, as soon as the large demonstrations against the deployment of American missiles began, numerous circles began to talk about neutrality again (for all the countries of Mitteleuropa) or a German-Russian rapprochement. Under Yeltsin, these debates first faded then became vivid again when NATO began to bomb Serbian cities in 1999. There was then a theatrical turn in Germany, as the Greens, who were part of the government, took up the cause for NATO, under the impulse of Joschka Fischer, the Foreign Minister: Fischer came from the radical left, which, precisely, in an earlier era, had virulently criticized American imperialism. Mohler was therefore more consistent than the folkloric and violent leftists who were quick to betray the ideals of their youth. The shift of the Greens to excessive bellicism is astonishing, causing a dismay that has been further amplified by the pathological Russophobia of the recent Green Minister Annalena Baerbock, who intended to promote a “feminist foreign policy.” All of this is diametrically opposed to the suggestions that Mohler made during his metapolitical and political career.

In the West, we are seeing today American cultural hegemony, declining birth rates, empty churches, and “wokeism” redefining social norms… In the face of this picture, do you think it is really possible to produce a new form of life, a new politico-cultural synthesis? And if so, on what foundations could it be built?

In Mohler’s circle, it was mainly Caspar von Schrenck-Notzing who castigated American hegemonism over Germany after 1945, in his book Charakterwäsche. Die amerikanische Besatzung in Deutschland und ihre Folgen (Seewald, Stuttgart, 1965 – several successive editions by various publishers). Caspar von Schrenck-Notzing explained that the “re-education” desired by the American occupation authorities had completely sterilized the German national character, preventing the emergence of a stable and fertile policy for the center of Europe. The book is now a classic for understanding the German post-war period.

Birth rate problems, although important, were hardly mentioned by Mohler. Being neither Catholic nor Protestant, Mohler was not concerned with the emptying churches. However, he sometimes liked to call himself a “Kathole,” which means having the same political attitudes as Catholic circles, like Carl Schmitt, without being interested in religious and parish life or theological problems.

There was no talk of wokeism in Mohler’s time. He was nevertheless, like all men of the right, sensitive to the throes of decline and decadence, which, for him, was the result of an outdated liberalism at the start, which went mad in the United States, was timidly implanted in Europe during the interwar period, and deliberately so since the Marshall Plan. Liberalism is a “general idea” according to Mohler, which leads to political quietism in a consumerist atmosphere: to this soft liberalism, to this liberalism from before the more aggressive neoliberalism, it was necessary, he said, to oppose myth, in the manner of Sorel. The new myth, if it ever comes about, will be the only one that can save us: Mohler did not believe in an “intellectual synthesis,” in a rigorously constructed conceptual system, in the manner of Hegel, which would have a rational answer for everything. Such constructions are sterile and will not move people. The mobilizing myth, which gives an axial impulse, turns the sphere of history in a new direction and will be the only one that is fertile. This myth should always have a catchy, beautiful, and suggestive visual support, similar to Mexican muralism (to which he dedicated a text of great interest) or Irish wall frescoes or posters from Mao’s China.

Personally, as a reader of Mohler since I was nineteen, I believe the solution to Europe’s ills will only come through a return to classicism, a classicism carried by new and strong images, mythologized according to criteria that artists will develop when the time is right, to pave the way for strong personalities who will influence the course of things, of the res publicae. For time is spherical, not linear and not repetitive/cyclical, as Mohler explained in the introduction to the 1989 edition of his thesis on the German “Konservative Revolution.”