Luga Fumagalli, a member of the Italian Oscar Wilde Society, also contributes to the Radio Spada blog and the bimonthly journal Saint Austin Review. His work focuses particularly on the study and promotion of leading figures in British Catholicism over the past two centuries. Among them, Tolkien stands out as a central figure. We spoke with Fumagalli about Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings.

Could you briefly introduce Tolkien and assess how his Catholic faith influenced The Lord of the Rings, as well as his place in the English Catholic-conservative tradition and, more generally, within the British right?

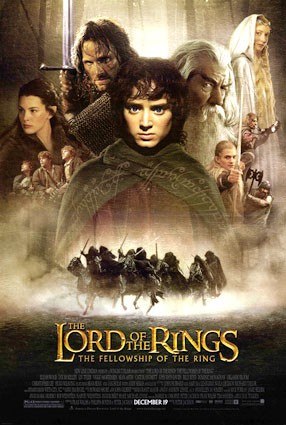

J. R. R. Tolkien (1892–1973) in truth needs no introduction, being one of the best-known and celebrated authors of the twentieth century, thanks to the enormous success achieved with The Hobbit (1937) and, above all, with the trilogy of The Lord of the Rings (1954–1955), the latter relaunched in the 2000s thanks to Peter Jackson’s excellent films (whereas his Hobbit trilogy is rather mediocre, with screenplay choices that are nothing short of embarrassing).

Originally from South Africa and a Catholic from his youth following his mother’s conversion, Tolkien was soon orphaned and placed in the benevolent care of the Oratorian priest Francis Morgan. He later fought on the Western Front during the First World War, married, had four children, and spent his entire career as a professor at Oxford University, first of Anglo-Saxon language and literature and then of English language and literature.

His desire to write stories was born of his profound love for ancient languages, which even led him, as a private pastime, to invent new ones. Middle-earth, in Tolkien’s own words, first took shape in his imagination in order to provide a context, a place, and a history for the fanciful dialects he was inventing, which later became those of the Elves and other peoples in his books.

Turning to the religious question, for the English writer Catholicism was something to be taken with utmost seriousness: he went to Mass every day – Carpenter devotes a few pages of his biography to this habit – and he suffered greatly from his friend C. S. Lewis’s aversion to the Church of Rome, as well as from the lukewarm attitude of his wife, Edith Bratt, who had reluctantly left behind the Anglicanism in which she had been raised in order to marry him. He was devoted to the Virgin Mary, and a 1941 letter of his, focused on the value of family and marriage, ends with a moving praise of the Blessed Sacrament; more generally he attached great importance to the cult of the saints, an attitude partly linked to his aversion to esotericism. He wrote that the saints are those who, despite their imperfections, never completely bent their hearts and wills to the corrupt logic of the world and for this reason remain indispensable points of reference.

His faith was seriously tested only during the years of the Second Vatican Council, when between 1962 and 1965 the Church began a process of theological-doctrinal aggiornamento that inevitably sparked controversy. In addition to the Oxford professor, many leading figures of the English Catholic literary revival adopted skeptical or critical positions toward the reforms promoted by the Council. Few were enthusiastic: most intellectuals expressed reservations, and Tolkien too experienced conflicting feelings about what was happening. George Sayer, who spoke at length with the professor during the 1960s, told Joseph Pearce in an interview that Tolkien’s Catholicism had a “traditional” character: “He was a very strict Catholic. He was very orthodox and old-fashioned, and he opposed most of the new developments in the Church at the time of the Second Vatican Council.” Similar words were used by John Tolkien, the son who became a priest in the 1940s: according to him, his father was against the changes, especially the loss of the Latin Mass.

Tolkien’s criticism was mainly directed at those who claimed to return to an alleged original purity, considering absurd the idea of uprooting a tree to search for its seed: that seed no longer exists; the trunk, the branches, and the leaves are its natural evolution, certainly not a betrayal.

Nevertheless, given his mild character and lack of interest in strident polemics, he did not stir up useless disputes and, despite his struggles, out of sheer spirit of obedience, eventually adapted to the new course (his spiritual torments are described in detail by Holly Ordway in Tolkien’s Faith).

The Lord of the Rings was inevitably marked by its author’s faith. Not so much because some characters resemble figures from the Christian tradition – one might think, for example, of the Elf Galadriel, who has certain traits in common with the Virgin Mary – but above all because the sensibility that animates the story is distinctly Catholic. The Lord of the Rings is therefore a Catholic work not because it should be understood as a religious allegory – a mistaken interpretation into which more than a few critics have fallen – but because, as the American writer Flannery O’Connor said about the so-called “Catholic Novel,” it is a text in which truth, as Catholics understand it, has been used as a light with which to view the world. Charity, selfless heroism, sacrifice – these are all recurring themes in the pages of The Lord of the Rings.

Precisely because of certain points of contact between his worldview and political conservatism, Tolkien has never ceased to fascinate certain circles of the Anglo-Saxon right, both English and American. Even though he always displayed a certain disinterest in party politics – with provocative flair he wrote: “My political opinions lean more and more to Anarchy (philosophically understood, meaning abolition of control, not whiskered men with bombs) or to ‘unconstitutional’ Monarchy” – liberals and neoconservatives have tried in every way to present the Oxford professor as one of their own. It is therefore no surprise that some of the most in-depth studies on Tolkien’s political philosophy have come precisely from those circles: one might think of Celebrating Middle-Earth: The Lord of the Ring as a Defense of Western Civilization by John West, or the more recent Hobbit Party by Jonathan Witt and Jay W. Richards. In the years of the “clash of civilizations,” moreover, certain sections of the American press raced to draw comparisons such as that between the second volume of The Lord of the Rings, titled The Two Towers, and the tragedy of 9/11, or proposing analogies like Sauron–Saddam. These are obviously nonsense that require no further comment.

Finally, it is worth noting how, over the decades, parts of the left have also engaged in creating the myth of the “fascist Tolkien,” with books such as Gentility and Powerlessness: Tolkien and the New Class by Fred Inglis, in which The Lord of the Rings is defined as a reactionary and racist epic. Here too, comments are superfluous.

Even though Tolkien rejected the idea of allegory, to what extent is it legitimate to read the conflict in the work in light of the Second World War (Orcs = fascism, Saruman = Prussian militarism)?

In my view it is always dangerous to apply the criteria of allegorical reading to a work as complex and multilayered as The Lord of the Rings. Many scholars have fallen into such a trap. The risk is to reduce Tolkien’s masterpiece to a single dimension, forgetting its long gestation and how the author poured into it all of himself, both his lived experiences and his ideas.

In Tolkien’s biographical arc, war played a major role – he was a soldier during the First World War and a witness to the horrors of the Second – and battles and epic clashes are certainly not lacking in The Lord of the Rings. Moreover, Frodo’s mission unfolds against the backdrop of a truly global conflict involving Middle-earth.

That said, reading The Lord of the Rings in light of the Second World War is a legitimate and relevant approach, potentially capable of providing interesting insights; however, one must not pretend that this interpretive key exhausts the complexity of the book or of certain aspects of it. For example, Saruman may indeed bear some resemblance to German militarism, but he is much more than that: in him takes shape the will to dominate and use violence that is a common feature of all men of every age. The same goes for the orcs and Nazi-fascism. Some have even claimed to see in the Ring an allegory of the atomic bomb, forgetting that around this fascinating and dangerous object Tolkien built a refined analysis of the phenomenology of power.

By way of contrast, one can point to a virtuous example of scholarship in the same field: John Garth, in Tolkien and the Great War, does an excellent job of detecting numerous analogies between what the Oxford professor experienced in the trenches and certain passages of The Lord of the Rings – insights also taken up in the biopic Tolkien – without any pretense that his reading exhausts the depth of the story.

How can one explain the shift of the book from being an icon of the hippie counterculture of the 1960s to a “secular sacred text” for many readers today?

It is fair to say that, at different times, just about everyone has been a Tolkienian: from neo-fascists to hippies, from environmentalists to Catholics, from pacifists to neopagans, from revolutionaries to conservatives. The Lord of the Rings has been taken up as a reference text by groups or movements that thought they saw in it a confirmation of their values. This happened because of crude misunderstandings and “ideological” readings: people wanted to exalt the convenient detail while erasing the rest. Saruman cuts down trees and the Ents rebel? That must mean Tolkien supported the Greens. Forgive the easy irony, but that is more or less what happened.

Again, the complexity of The Lord of the Rings was erased, a work that, like every “classic” of literature, is such precisely because it touches on so wide a range of themes and topics as to embrace the totality of human existence; and precisely for this reason it is destined never to go out of fashion. The reader will always be able to approach it and see himself reflected, as in a mirror, with his own fears and aspirations, weaknesses and hopes. In other words, The Lord of the Rings has the power to reveal man to man, something that is already irreducible to easy labels.

The danger that Tolkien’s masterpiece faces today, absorbed as it is into pop culture, is that of being placed on the same level as other successful fantasy novels, as if the Oxford professor’s work were the result of a nerd’s infatuation with elves, dragons, and the like. In fact, as has been said, it is much more: The Lord of the Rings tells the epic of humanity; certainly it does so with stylistic devices foreign to the naturalistic novel, but it is no less effective for that – indeed, quite the opposite.

What impact have Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings had on contemporary right-wing and conservative political movements?

Since I have already said something, albeit briefly, about the British and American cases, it seems more interesting to focus on Italy, where The Lord of the Rings was first published in complete edition only in 1970.

As a reaction to the demonization carried out by progressive critics, who looked down on any work of fiction not aligned with the dictates of realism, from the mid-1970s onwards there began a systematic process of appropriation of Tolkien’s universe by right-wing parties and movements, first and foremost the Italian Social Movement (MSI), which made The Lord of the Rings a reservoir of symbols, iconographies, and slogans (that same party included the young Giorgia Meloni, now head of government and a noted admirer of Tolkien). From a sociological point of view this is a unique case, since no other narrative cycle in Italy has been able to catalyze such widespread attention.

Gianfranco De Turris, one of the most prominent intellectuals of that world, has repeatedly pointed out the typically Italian relationship between fantasy literature and the right: “The fiction of Tolkien and heroic fantasy was, so to speak, more connatural to the spirit of the right-wing youth, to his way of living and feeling, to his personal and collective mythology.”

The outlets where militant press was circulated sold hundreds and hundreds of copies of The Lord of the Rings, and in those same years the band Compagnia dell’Anello was formed, still active today. In short, around Tolkien’s work there developed a dense network of activities aimed at conveying the ideological message and political values of the right beyond its usual circles.

In 1976, when the MSI decided to found a new magazine to relaunch its conception of women and to show that they were by now emancipated from Mussolinian stereotypes while also far removed from feminist ideas, the title chosen was Eowyn. The princess of Rohan, niece of King Théoden, according to the editors represented the perfect model of a new way of living femininity, both combative and “reassuring.”

The “Hobbit Camps,” a kind of festival-assembly-concert in response to similar events organized by various left-wing groups, also marked the history of Italian Tolkien criticism, not only because many of today’s most active Tolkien scholars took part in them, but above all because within those experiences matured an allegorical reading of The Lord of the Rings, very similar to that present in the introduction that Elémire Zolla had written for the first Italian edition.

It was only after the transformation of the MSI into the National Alliance that Tolkien’s imagery began to be reused again, on an even larger scale than before, bringing the Oxford professor into a convenient canon of writers and thinkers not only intrinsically right-wing, but valid for a “sentimental education” of the future militant. Whereas at the beginning the references, even in the form of simple quotations, had a certain depth, over time the National Alliance’s make-over reduced The Lord of the Rings to gadgets and merchandising, much as still happens today with Fratelli d’Italia.

To complete the picture, it must be said that in recent decades Catholics in Italy have also been able to rediscover Tolkien thanks to various studies dedicated to the spirituality of the Oxford professor and his work, and the left too has learned to re-evaluate him. The immediate consequence has been the emergence of alternative visions capable of challenging certain interpretive simplifications from the right, starting precisely with that allegorical reading mentioned above.

On what historical foundations did the 20th-century English Catholic writers (Chesterton, Belloc, Dawson, Waugh, Tolkien, etc.) draw, and how did they relate to each other in a predominantly Anglican cultural environment, thereby creating a Catholic conservative intellectual current?

I believe it is first of all necessary to make some distinctions: on the one hand, there is the general question of Catholics in England – in the second half of the 19th century these were predominantly poor Irish immigrants – and on the other hand, there is the small niche of intellectuals, many of whom were born Anglicans and only later converted to the Church of Rome, usually coming from socially and culturally exclusive milieus.

It was therefore numerical and sociological rather than religious reasons that led the majority of British Catholics in the last century to vote for the Labour Party.

If, however, one carefully analyzes the thought of the various intellectuals – who collectively were always perceived as more conservative than their working-class co-religionists – one discovers a wide variety of positions: from admirers of fascism (above all Douglas Jerrold) to radicals and Catholic Marxists, to left-leaning Catholics like Greene.

Conservatives, in the sense of nostalgics for a more or less mythical past, were in fact very few: even those closest to Jacobite claims or to the myth of Merry England – the rural medieval England, a small province of Catholic Europe – were acute enough to realize that reality, unfortunately, left little room for such fantasies, and that if one really wanted to change things, one had to act hic et nunc (here and now).

To be admirers of the past, moreover, did not necessarily mean to be proponents of conservative policies; quite the opposite. To cite the most emblematic case, the distributists – of whom more will be said below – opposed capitalism, taking as their model the medieval social system. Medievalism also played a decisive role in the re-emergence of Scottish and Welsh nationalism.

Nor were there fervent defenders of the institutions of the Empire, those very institutions that, until only a few decades earlier, had done nothing but persecute Catholics loyal to Rome (let it be recalled, in passing, that dioceses were re-established in England only in 1850; this means that before that date the country was considered mission territory, on the same level as a remote region of Africa or Asia).

A completely different matter arises if by “conservative” one means those Catholics who, faced with the sad spectacle of an increasingly secularized world, came to regard modernity with more or less acute disdain. Chesterton, Belloc, Dawson, Waugh, and Tolkien – although very different personalities – were kindred spirits in this respect. Some of them entered public debate as journalists or even through active politics – Belloc, for example, sat in Parliament for the Liberal Party – but these remained sporadic cases.

Did Chesterton and Belloc’s distributist model merely reflect a conservative nostalgia in the light of contemporary critiques of liberal capitalism and socialism, or did it present a practicable alternative vision for the future of the modern world?

The relationship between individual and society, that is, person and state, is one of the crucial knots of modernity. Belloc tackled it at its root by recalling the perfect analysis of Cardinal Manning, Archbishop of Westminster at the end of the 19th century, according to whom every human conflict is ultimately a theological conflict. In other words, Belloc perfectly understood that the drama of modernity was to be resolved in the choice between God and idols, between Christian civilization and that new paganism made of lust, power, and money that was spreading everywhere.

Chesterton also spoke out on this point. In an essay written in 1926 after visiting the United States he commented: “The madness of tomorrow is not in Moscow, but in Manhattan.” The new heresy of which the English writer spoke was none other than hedonism elevated into a system, which leads to selfishness, domination, and – in the long run – self-destruction.

Hence the defense of the Middle Ages that Belloc and Chesterton undertook with singular passion, supported by the Irish Dominican Father Vincent McNabb. Their stance had nothing nostalgic or backward-looking about it; it was simply a matter of looking to the concreteness of institutions, lifestyles, and social realities more in harmony than modern ones with the truth and needs of the human being. And since the three did not like to stop at words, they soon moved into action: together with other friends they founded a periodical, G.K.’s Weekly, and a movement, the Distributist League, with the purpose of spreading a political and economic idea that was an alternative both to capitalism and to communism, drawing on the experience of medieval guilds as well as on Catholic social doctrine (though not all distributists were Catholic). The movement’s motto was “Freedom through the distribution of property,” and circles were soon opened throughout the United Kingdom.

For the distributists, the only solution to the problem of social injustice caused by excessive concentration of wealth was neither the abolition of private property nor the adoption of those corrective measures to capitalism suggested by Keynes, but the distribution of the ownership of the means of production. In this way, the only context would be created in which it was truly possible to abandon progressively a servile condition.

Although animated by ideas fascinating on paper, distributism did not succeed in practice, falling into crisis already at the end of the 1930s, after Chesterton’s death. Nevertheless, its ideas survived, migrating overseas and influencing a significant portion of American Catholics, among them Dorothy Day, a historic figure of Christian social thought and champion of workers’ rights. Distributist ideas are also present in the works of Ernst Schumacher, who in 1973 published Small Is Beautiful, a book that questioned the very foundations of Western consumerist culture.

Today, some points of contact may perhaps be seen with those who support so-called “sustainable degrowth,” aimed at reducing the environmental and ecological impact of human activity by reducing waste. There still exist groups that claim distributist ideals – in Italy, for example, there is the Movimento Distributista Italiano – but these are minority circles, struggling to make themselves heard in the public debate with proposals that can be concretized in a world completely different from the one in which Chesterton, Belloc and their companions operated.