Aisha Khalid is one of the most important representatives of miniature art today. Drawing on the miniature tradition, she brings a new language and depth to contemporary art. We had an enjoyable conversation with Khalid, who transforms miniature into both a personal and political means of expression, about miniature art and her education.

How did your journey with miniature painting begin? Why did you choose miniature as your form of expression?

When I decided to start my career as an artist, I chose to study miniature painting because it is a traditional technique deeply rooted in the history of the Islamic world. I was fascinated by Mughal-era miniature paintings—their refined sense of colour, intricate ornamentation, and profound symbolic meaning. I was also drawn to the fact that they are painted on paper using water-based colours—no mess, no smell of oils—allowing the artist to work peacefully while sitting on the floor.

When I began learning this technique as a student, I realised it had incredible potential for evolution. However, I noticed that most artists at the time were simply making replicas of old works from the Mughal or Persian traditions. From the very beginning, I decided I would use this technique to express my own feelings and ideas, rather than merely copying historical paintings.

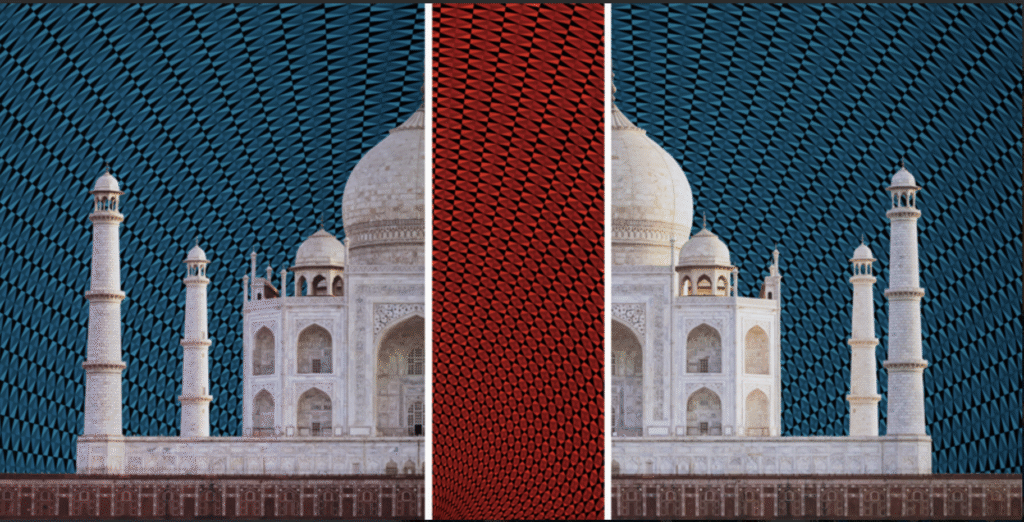

My journey started in the 1990s with postcard-sized works, and over time, the scale of my paintings grew—from small works to large-scale pieces created with the same level of detail and precision. Eventually, my practice expanded from large paintings to site-specific installations within architectural spaces.

The term miniature painting was coined by the British during colonial times, limiting and narrowing the perception of its possibilities. I challenged those conventions, bringing miniature painting into the realm of contemporary art. Today, my work is recognised worldwide as part of the contemporary art movement, while still rooted in this rich and historic technique.

Today, efforts to modernize miniature painting are seen by some as a betrayal of the art form. In your view, what is the essence of miniature? How can it be expanded while preserving that essence?

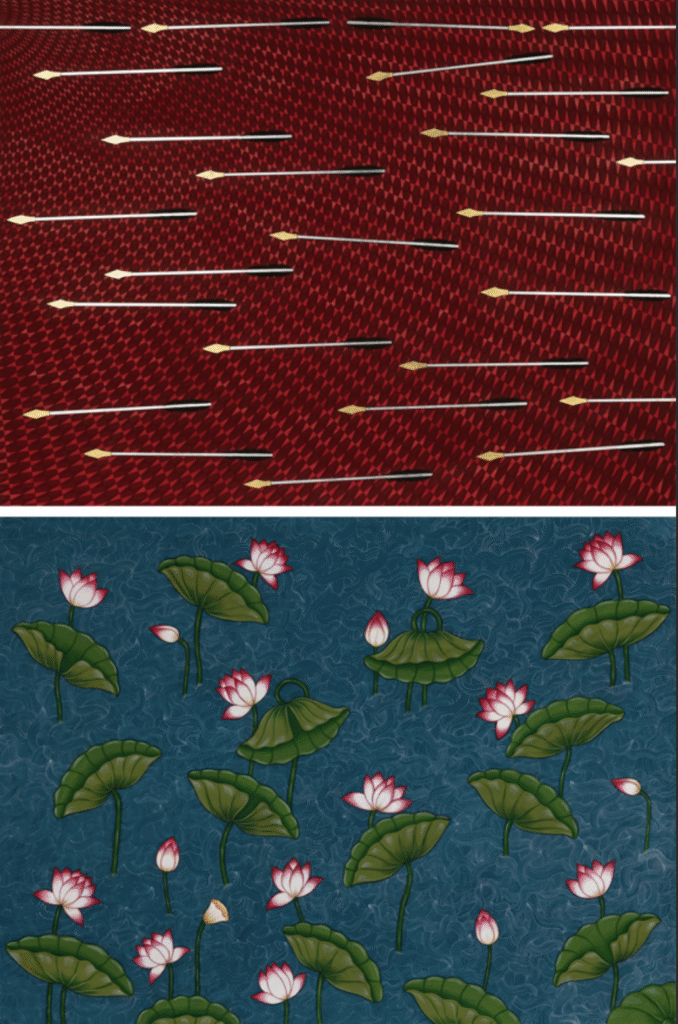

Miniature painting is not just a technique — it is a deeply rich way of expressing one’s thoughts. It involves a whole tradition of materials and processes: preparing the paper surface known as wasli, making brushes from squirrel tail hairs, grinding and mixing pigments, controlling the intensity of colors, and mastering the art of gilding. Each step is essential to the craft and requires patience, discipline, and respect for tradition.

Beyond technique, miniature painting has its own distinctive visual language: the treatment of the surface, the flatness of form, and the two-dimensional depiction of architecture. Historically, it served to record events and histories in pictorial form, often as part of books or albums. Because the artist had to capture many aspects of an event within a single small frame, two-dimensionality of space became a deliberate and defining feature. Ornamentation and illumination were also integral, adding layers of meaning and beauty.

When adapting miniature painting into contemporary practice, there is always a risk of losing this sensibility. I was trained in the strict traditional way under a master who was deeply committed to preserving the old methods, and through that I developed a strong technical foundation. Today, I work on a very large scale, yet the essence of traditional miniature painting still runs through my work — even though I have broken certain boundaries.

Ultimately, it depends on what you believe. I follow the Sufi path, and my work is inspired by the poetry of Maulana Rumi. As a spiritual person, my sensibilities grow from my beliefs, and I feel that art inevitably reflects who we are as human beings. For me, preserving the essence of miniature painting means honoring its spirit — discipline, symbolism, and depth — while allowing it to evolve in a way that stays true to the heart of the tradition.

Around the world, many miniature artists are emerging. Some modernize the techniques used, while others modernize the subjects they depict. Why do you think influential theoretical texts and intellectual debates have not emerged within the field of miniature art?

I think that in today’s modern world, words and works connected to tradition are often exploited under the label of “craft.” If we look at craftsmanship in our Islamic history and heritage, it was deeply integrated into everyday life — and in many Muslim countries, it still is. Whenever the question arises about “reviving” art and culture, I always say: we don’t need to revive it, because it is already alive within our culture — we only need to evolve it.

From embroidery, calligraphy, and jewellery-making to ceramics and many more, these crafts remain closely tied to our lives and identities. I don’t believe that craftsmen lack meaning in their work simply because they are not classified as “artists.” Their creations do carry meaning, even if it is expressed in different ways. The same applies to miniature painting: many artists follow the traditional techniques but do not use them as a medium to raise their voice or explore deeper concepts. On the other hand, some artists evolve both the technique and the conceptual dimension, bringing miniature into a contemporary dialogue.

One reason influential theoretical texts and intellectual debates on miniature painting have not emerged internationally is that the field is not properly institutionalised. In Pakistan, contemporary miniature painting is well-received in mainstream art practices because it is embedded in academic structures — students can pursue degrees in it, with a formal curriculum in place. We need to bring the same level of institutional support to all traditional crafts, so that people can learn them in depth and then express themselves through them in contemporary ways. This is how these traditions can meaningfully connect with the wider world.

Many practitioners are highly skilled artisans but may not have platforms or resources to publish theoretical writing. Also, miniature’s revival in the 20th century was largely driven by studio practice rather than academic discourse, so the written tradition lagged behind the visual one. What’s needed is not just more artists, but artist-scholars who can articulate the medium’s evolving language and politics in ways that reach both art history and contemporary theory.

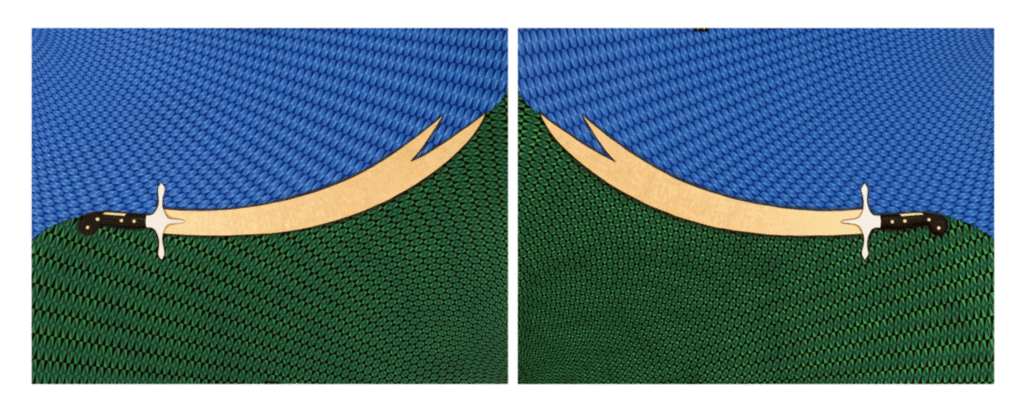

You use miniature both as a cultural and a protest medium. How does miniature, especially when it breaks free from the page, gain expressive power compared to other art forms?

I use miniature painting as my tool of expression—it works for me like my own mother tongue. Just as one can express their feelings most naturally and deeply in their own language, I find miniature to be the most direct and powerful way for me to speak.

Whether my work takes the form of site-specific installations or commissioned projects, it is always loaded with social and political context. I think my voice is heard more clearly because I speak in my own way—through colors, symbolism, and the deliberate precision of my technique, which is often unfamiliar to the Western world. This has not only shaped my unique identity but has also turned my work into my signature and a powerful source of self-definition.

I believe tradition is not like still water that remains unchanged through the ages—it is like running water, flowing and reshaping itself over time. It must evolve to remain relevant. If we look at miniature painting during the Ottoman or Mughal periods, it was highly contemporary for its time; the artists were not merely copying the past. Historical works show us how the art form evolved with each era. There is no question, then, that we must also allow it to evolve today, in response to the realities of our own time.

Could you tell us about NCA and the Miniature Department? What kind of curriculum and content does it have? What did it provide you as an artist?

The Miniature Painting Department at the National College of Arts (NCA) is unique in how it combines strict, hands-on training in centuries-old techniques with the freedom to develop one’s own artistic language.

In the first two years, the curriculum focuses on building a strong foundation in the traditional craft: Wasli paper preparation – learning to layer, burnish, and prepare the handmade paper. Brush-making – crafting fine brushes from squirrel tail hair.

Pigment grinding & colour preparation – working with natural pigments to understand their texture, opacity, and layering potential. Copying historical works – studying and replicating Mughal, Persian, and other miniature styles to deeply understand proportion, ornamentation, and composition. As students progress, the emphasis shifts from imitation to innovation:

Developing original concepts while still using the miniature painting grammar.

Exploring scale — from intimate page-sized works to large site-specific installations.

Integrating miniature techniques with contemporary themes, media, and contexts.

For me, NCA’s miniature department didn’t just give me a skill — it gave me a language. It rooted me in a tradition that is intellectually rich, visually sophisticated, and deeply connected to our history, while also encouraging me to push its boundaries and make it relevant to the present.

As a Muslim artist, after you expressed your stance on Palestine, did you face any reaction from the Western art world?

I always try to speak out on societal and political issues loudly and without fear, and my stance on Palestine is no different. Every step we take has consequences, and I am always prepared for them. I see art as my power and my freedom of expression, and I use it boldly, without fear. I do not connect myself to this world; rather, I connect with nature and with the One I believe in the most. I have also seen many good people in the West protesting for Palestine and striving to stop this war. Some of the most significant demonstrations we have witnessed in recent times have taken place in Western countries.