Hans Freyer, though known for his work in sociology, has secured an important place within the Conservative Revolution movement through his book Revolution from the Right. We discussed this topic with Victor Van Brandt, an independent researcher living in England. Van Brandt is also the author of the Substack blog Esotericist’s Newsletter and focuses his work on developing a folkish perspective adapted to the contemporary Anglo-Saxon world. We discussed Freyer and The Revolution from the Right with him.

Classical right-wing ideologies and the idea of revolution seem to be at odds. How does Freyer overcome or redefine this contradiction? How did he conceptualise “revolution from the right”?

Yes, the concept of revolution does appear to be in conflict with traditional rightism. Many of the 18th and early 19th century rightists are conspicuous for their critique of revolution, in particular the French Revolution of 1789: Burke, De Maistre, etc. The basic concern is that revolutions, because they aim to transform society, will end up sweeping away the traditional customs, beliefs, institutions, and even religious beliefs of a society. From a conservative point of view, this would be anathema. So how does one make sense of the attempt to combine conservative and revolutionary ideas?

Two things are important here: one, that the conditions in which thinkers like Freyer found themselves seemed to render traditional conservatism impotent; two, that this necessitated either an abandonment of conservatism or a reconceptualisation of it. Since Freyer and other thinkers of the period thought that conservatism still had important insights, they didn’t want to abandon the title of “conservative”. What had to change was the negative stance of conservatives towards revolution.

To put the impetus towards revolutionary conservatism into perspective, we should briefly depict the condition of Germany at the time. Germany had suffered a humiliating loss in WWI. Under the Treaty of Versailles it lost territory, had to make unsustainable reparations payments, and saw the German military reduced to a shell of its former self. Following WWI, the monarchy was abolished, and a new republican system of government was established during the November Revolution. In this void, various ideological groups saw an opportunity to impose their vision on Germany. The November Revolution, which lasted from late 1918 to August 1919, had briefly threatened a shift towards Bolshevism. That threat had receded for the time being, but the possibility still loomed on the horizon. The Kapp Putsch in March 1920, led by Wolfgang Kapp and Walther von Lüttwitz, aimed to undo the aforementioned revolution, but it was unsuccessful. And then there was the National Socialists’ Munich Putsch in November 1923. Leaving aside these radicals, it was clear that the Weimar Republic was not doing well. Politically, economically, and culturally, it repulsed nationalists and conservatives. The electoral system itself was unstable, and it was difficult to form strong governments. It was often necessary to govern through coalitions, but due to the strong political disagreements between parties, this was difficult and led to frequent crises. The reparations payments imposed by the victorious Allied Powers were unsustainable, and the new state’s attempts to deal with this led to hyperinflation, causing misery for millions of Germans. On the cultural and intellectual front, new artistic movements such as Bauhaus, Dada, and the New Objectivity movement were opposed by many conservatives and nationalists as degenerate; jazz music, which was perceived as a foreign, American phenomenon, soared in popularity; many young people turned towards what was perceived by rightists as a hedonistic and nihilistic lifestyle, focusing on consumerism, sex, and partying, rather than any higher values; and finally, in the Weimar Republic various leftist currents proliferated in the intellectual sphere, with every conservative value from race, nation, to traditional marriage coming into question.

In the light of all of these facts, it is clear that a revolutionary shift had already occurred in Germany, and it was not leading in a direction that appealed to most conservatives. When the enemies of conservatism have already had a chance to transform society, a conservative, if he has any moral fibre, has no choice but to advocate a new revolution to put his country back on the right path.

If one is dissatisfied with the system in which one lives, there are two practical possibilities: either the system can be salvaged, in which case one must be a reformist, or the system cannot be salvaged, in which case one must be a revolutionary. Freyer (along with many other rightists) believed that not only was the Weimar Republic chaotic and unstable, but that it was morally illegitimate. On this view, even if it could be salvaged, it ought not to be. Thus, to achieve something like a desirable social order, revolution was the only path forward. Essentially, one had to choose between two revolutions: the ongoing revolution from the left that had produced the Weimar Republic, or another revolution from the right that would sweep it away and put Germans back on their proper historical path. The choice was clear for someone like Freyer.

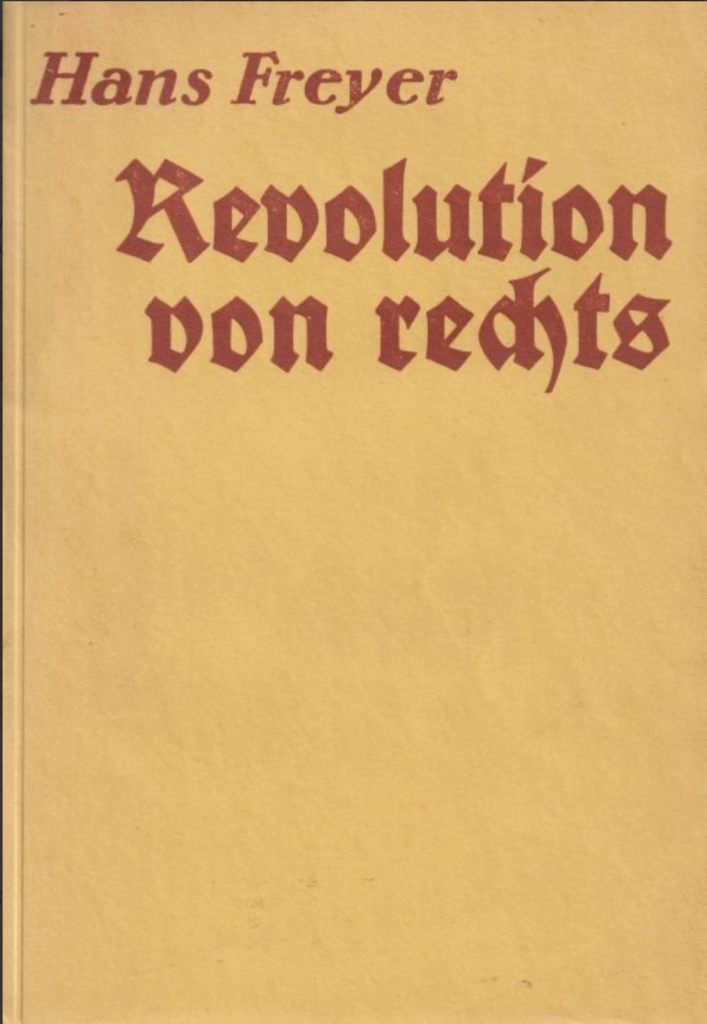

I have sketched out the circumstances in which Freyer was writing. Now it would be worthwhile to address his ideas in more detail. The main source for understanding Freyer’s views on revolution is Revolution von Rechts (Revolution from the Right), a pamphlet published in 1931. Although Freyer had written several works before this, and had already developed some of his distinctive ideas, this pamphlet was his first attempt to influence practical politics directly through his writing.

The moderate right had been discredited; new crises called for new praxis and institutions. Freyer’s thesis was that, whereas past revolutions had been left-wing in nature, the next revolution of the 20th century would come from the right. We will deal with what a revolution from the right looks like in a moment; but let us first be clear on what a revolution is. A revolution is a process of replacing one social or political order with another based on different principles. A revolutionary situation exists where distinct groups face each other, whose continued co-existence is impossible. Struggle between these groups must result, and the outcome of the struggle will determine whether the present system will exist, or whether it will be replaced with a different one.

All manner of activities fall short of revolution. Criticism is not revolutionary, for Freyer characterises it as a mere “mental reservation”; similarly, lobbying for concessions from the state, as with trade unionism, is not revolutionary; nor are organised masses necessarily revolutionary. These things are fundamentally compatible with the continued existence of the system. All the talk in the world will not bring about a revolution. As Freyer put it:

Revolution begins only when critique becomes flesh and blood; when a corporeal and explosive core grows in the shell of the present; when the knot is tightened inside reality itself; when the free forces that are not absorbed by the present represent not only in their better knowledge the judgement of time, but in their existence the historical change of time.

A revolutionary will refuse offers of a sinecure, or pardon by the ruling class if he ceases his activities. He refuses to assimilate, and is the living incarnation of principles opposed to those upon which the current system is built.

Freyer argued that the left had been absorbed into the system. A new idea had emerged in most of the highly industrialised Western countries, what Freyer termed the “social” idea. The heart of the social idea was the secularised notion of charity. Factory regulations, trade unions to lobby for better conditions, poor relief, and a number of ameliorative measures were devised under its banner. Any left-wing group had to reckon with the fact that most workers were more or less satisfied with these conditions. And thus what could have been a revolution was dampened into mere reform, and the spectre of communism was exorcised. The proletariat even championed the social idea themselves, thereby damning the revolution to failure by tying their interests into its preservation. As Freyer put it:

After all, they already had very different things to lose than their chains, namely their specific rights and the possibilities for their further development.

The essence of the system remained the same, for they were not fighting for the creation of a new system, but for a better place within the present one. Freyer calls this process “the liquidation of the nineteenth century”, because the revolutionary potential of that most potentially revolutionary of previous centuries was nullified. The revolutionaries themselves were distorted and coopted: their “negative”, which aimed at destroying the system, was turned into a “positive” which reinforced it. What strike many as revolutionary developments were really quite compatible with bourgeois industrial society: “no new principle breaks into it”.

However, the absorption of the revolutionary class—the proletariat—into the service of this order does not end the prospect for further revolution. Indeed, as Freyer says:

It is precisely the dismantling of the revolution from the left that opens up the revolution from the right.

Rather than the proletariat, the organising principle of the revolution from the right is the folk. “Revolutions”, we are told,

[…] are not “developments”, not “progress”, not “movements”. Rather, they are dialectical tensions that are charged and recharged—and whose impact either becomes history here and now—or not.

The incorporation of the proletariat into the service of the industrial order, of the recognition of the necessity and importance of all social classes, cleared a dialectic space within this order, turning the folk from a “vague idea” into a “historical reality”. The folk is “a new formation, its own will and its own right”. It rises above social classes and frees the forces it organises from their character as mere “social interests”. It is “the antagonist of industrial society”.

But what is a folk? According to Freyer, we must pierce through two “layers” before we can understand it. The first layer of the folk is the “nation”, in the 19th century sense i.e. in the bourgeois sense. This layer was overcome in Freyer’s time, because it was tied to the bygone 19th century. The second layer was a deeper one. It includes:

[…] the primal forces of history; decrees of the absolute; spirits that were very close to nature, incomprehensibly creative like it; a great immediate existence that works history but does not exude itself in any history.

The folk was in a process of forming into a front against industrial society, and it could not be known with certainty in advance, down to the last detail, what form its social organisation would take after a successful revolution. One could, however, reasonably ask what direction the revolution of the folk would thrust in. Freyer answers: “from the right”. By “right”, he does not mean “right-wing” in the typical sense, since he viewed this as a relic of the 19th century; rather, he meant that the folk isn’t simply one other interest group that wants to find its place in the system of interest groups, as was the case with the leftist revolutionaries and their “proletariat”. The revolution from the right means that the state will be liberated from its “centuries-long entanglement in social interests”, so as to build a new future out of the folk.

“Every historical situation,” we are told, “produces its own state”. A successful revolution brings about a new state: it does not merely seize the existing state apparatus, keeping it the same but changing the ownership. The revolution from the right will use its state to destroy the “past principle that dominates the present”, and it builds its state even as the old state still exists. The folk and the state are unified in the revolution from the right. Freyer’s conceptions of the folk and state go beyond, respectively, the shallow nationalism of the present, consisting in flag-waving and chanting of slogans, and the notion of the state as something above and separate from the folk, which creates the folk. A folk is a “field of forces”, and the state is, firstly, the tip of the spear with which it deals a deadly thrust into industrial society, and secondly the “concentrated energy” of the folk’s permanent action.

Freyer does give us some indication of what the social order will look like after this revolution. Politics will take precedence over economics. The land will go from being a mere factor of production to a living space for the folk. A new state socialism will be established in which the folk’s “field of force” is freed from “the heterogeneous ricochets of industrial society”. The technical apparatus of the system, as well as the concept of “the social” of the 19th century will be taken as a matter of course, not as a special achievement or feature of the system. Man will be free, but his freedom will only be within the framework of his folk, not as an isolated “individual”. People will not be organised into separate interest groups which compete with each other, but will see themselves as parts of a unified whole, and work for common ends.

Freyer concluded that a number of people were rising who carried within them the 20th century, who opposed the dying order of the 19th century. The front of the folk against industrial society was forming; in his view, this was the reason why the revolution from the right was “the content of the time”.

How is the link between culture, nation and state defined in Freyer’s thought?

The three concepts of culture, nation, and state are closely intertwined in Freyer’s thought, and it is perceptive that you have listed them in that order. It is best to explain each of them individually, and then show how each of them relates to the next concept.

Let’s address culture first. Culture, in Freyer’s view, is the externalisation of human spirit (he uses the term “objective spirit”) into lasting forms, such as symbols, norms, artworks, and institutions. These forms compose social life. What this means is that they are the things that bind individual human beings together into communities and peoples. We can easily see why this is so. Symbols are means by which human beings communicate with each other. They create a shared nexus of meaning which make peaceful coexistence possible. Norms establish common standards for behaviour, which impose a certain order on social relations and resolve uncertainty as to how to relate to other members of a social order. Institutions can serve various functions, but among them are governance and the facilitation of religious praxis. All of these are very powerful in forging links between individuals and integrating them into a greater whole. Now we can get into how this relates to Freyer’s anti-individualism. I have spoken of how culture involves the creation of “lasting forms”. Cultural products persist through numerous generations, meaning that not only the currently living generations are bound together by culture, but also the dead generations and those yet to be born.

This conception of culture has important implications for Freyer’s conception of a people (Volk). Culture stands in a reciprocal relation to a people. A culture both forms a people (literally, in Freyer’s words, giving them a shared Gestalt, or form) and in turn is constantly reformed by the living members of each new generation. It is inherently dynamic, not static. You cannot consider the one without the other. A people is a whole. It is not merely an aggregate of individuals, united by a “social contract”, as in liberal theory, but a collective entity whose members are fatefully bound together (he calls it a “Schicksalsgemeinschaft” or “community of fate”) by shared historical ties and culture. Freyer, unlike National Socialist theorists, did not conceive of a nation as based on race. He did, on occasion, mention blood and ancestry, but it forms no important part of his worldview.

Earlier we spoke of how Freyer conceived of culture as the externalisation of human spirit. Of these forms of “objective spirit”, the state is the highest. But of course, without a people possessing a shared culture, there would not be the unity require to produce a state. Accordingly, we can say that they are preconditions for the state. Whereas the people is the substance of political life, the state is the form of the same. This conception of the state was fundamentally opposed to the liberal one. It is not merely the guarantor of individual rights, but a “Gestaltende Kraft” or “formative power”, which is capable of shaping collective life. The state, thus conceived, could play a major role in overcoming the crisis of modernity. But this would require the harnessing of “subjective spirit”, that is, the spontaneity and creativity of individual subjects, to the project of the state.

So we can see that all three elements are inherently connected according to Freyer. A people/nation is a cultural unity formed by history, and the state is a form of organisation of the people.

In what ways does he differ from other conservative-revolutionary thinkers of the period (Jünger, Spengler, Moeller van den Bruck, etc.)?

It might be helpful to first “place” Freyer in relation to other figures of the period. Armin Mohler, in his classic work, Die Konservative Revolution in Deutschland 1918–1932, organised thinkers into three main groups: the Young Conservatives, the folkish movement, and the national revolutionaries. Freyer is usually seen as belonging to the Young Conservative group. The sorting of thinkers into groups is not entirely reliable, as there are differences with these groups as well, but it is close enough to reality to be useful.

Firstly, the style and nature of his intellectual work differed from many other conservative-revolutionary thinkers in that some of it was unusually systematic and academic. Many of the writings of his contemporaries came in the form of articles, historical works, and the like, but Freyer wrote numerous treatises, including Der Staat (1926) and Soziologie als Wirklichkeitswissenschaft (1930). He also wrote treatises specifically on ethics (Antaeus, 1918 and Pallas Athena, 1935), which was quite rare for conservative revolutionaries of the period. Freyer was formally trained in philosophy and sociology, and this is clear in his writings.

He differed from the folkish movement in two important ways. The first is that, whereas biology and biological race are absolutely central to the folkish worldview, they do not serve any significant role in Freyer’s view, which focuses more on culture and institutions. During the 1920s and early 1930s he did not produce any writings devoted to showing how race shapes history, or anything of the sort, as would be typical of the folkish movement. The second difference from the folkish movement is that he was more modernist than some folkish thinkers. Ruralism was a major concern for the folkish movement, in that rural life was seen as more conducive to racial health and cultural vitality. This view went hand-in-hand with a rejection of mechanised agriculture. In contrast, by the end of the 1920s Freyer had come around to a positive view of technology, believing that it can and should be harnessed in the interests of the nation. Jeffrey Herf devoted a great deal of space to a discussion of Freyer in his book, Reactionary Modernism, because he saw Freyer as a paradigm case of the attempt to combine a rejection of political modernity with an embrace of technological modernity.

Freyer also differed considerably from the views espoused by Ernst Niekisch’s National Bolshevik movement. He was not pro-Russian or sympathetic to Marxism, and did not advocate a proletarian revolution, still less a proletarian state. He also parts ways with Niekisch when it comes to international orientation in that, at least before the rise of the NSDAP to power, he was focused almost entirely on the domestic political order that he wanted to establish in Germany, rather than thinking of forming an international alliance against the West. Perhaps the most important difference between Freyer’s views and those of the national revolutionaries is that Freyer placed the state at the centre of his thinking. Jünger and Niekisch had both focused on types (The Worker, The Third Imperial Figure). For Freyer – and perhaps this is a legacy of the Hegelian influence on his thought – the state was the figure that stood over and above all of these things, shaping the German people into a folk community.

In contrast to many other figures of the Conservative Revolution, Freyer was more open to collaboration with the National Socialist movement. Moeller van den Bruck, Spengler, and Edgar Julius Jung all had disdain for Hitler and the NSDAP, even if there was some ideological overlap with them, due to their favouring an elitist approach. They wanted to create elite circles that would then influence or control political parties. The NSDAP, by contrast, sought to create a mass movement that would sweep it to power. Those on the side of the mass movement actually turned out to be right here. Freyer ended up collaborating with the National Socialists, signing the Vow of allegiance of the Professors of the German Universities and High-Schools to Adolf Hitler and the National Socialistic State in 1933. However, it’s doubtful that he could ever have been decisively classed as a National Socialist ideologically. As I have already pointed out, he didn’t give biological race the prominent position in his writings that typical National Socialist writers did, and he never joined the NSDAP. During the denazification proceedings after the war he was classified as a “Mitläufer” or “follower”, indicating that he was not viewed as a serious offender.

Thus, overall there were some considerable differences between Freyer and many other conservative revolutionaries, particularly those of the folkish and national revolutionary factions. He was not simply a reflection of the broader milieu, but a valuable thinker in his own right.

Technology is a central issue discussed both among conservative revolutionaries and in post-industrial society. What is Freyer’s approach to technology?

Freyer was concerned with the issue of technology from the very beginning of his career. He used the word “Technik”, which we might translate as either “technology” or “technique”. This is important, because the word “technology” in English might make people think of machines, whereas the phenomenon of technique is much broader in scope. Technique covers any instance in which scientific or other knowledge is utilised to create processes, methods, and products for human ends. Thus, anything from a production process used in a car factory, to the car itself, to marketing methods (informed by social psychology) can come under this heading. It is easy to see, given this conception of technique, why Freyer came to place such importance on it. Technique is an integral and inescapable part of modern culture.

In his early work, Freyer was concerned about the possibility of Man losing control of technique, and coming to be dominated by his own creation. As he said in his Habilitationsschrift, published in 1921:

…the more completely an area of culture is mechanised, i.e. the more extensive and multi-layered the connection of means is that is inserted between the initial need and its final satisfaction, the more the apparatus of means grows into an independent being, the greater is the danger of its tyranny over man.

Freyer’s early ideas on technology and technique more broadly were refined over time through numerous books and essays. He employed the same dichotomy between Kultur and Zivilisation that other thinkers of the period such as Spengler did. Kultur refers to a social order that is organically developed, one in which myth, religion, folkways, and community are powerful influences. Zivilisation, in contrast, is a decadent stage in a social order’s history, in which the above-mentioned elements have degraded or even disappeared. Sentiment and faith are replaced by cold, life-destroying Reason. Technology, in the early view of Freyer, is emblematic of the latter. It threatens to destroy human autonomy and sweep away organic cultures. Notably, the primacy of economic concerns in the life of the nation is something that Freyer associated with Zivilisation, and accordingly he rejected it in favour of the primacy of politics.

However, despite these concerns, in later years Freyer came around to a more optimistic view. In his work Der Staat from 1926 he suggests that technique could become a positive force, being utilised by the state for the collective interest through a system of centralised planning. Again, we can see that optimism about the potential of deliberate human action to change history characterises his work during this period. As he said, “technology is not an end in itself, but a means of shaping history.” Technique would be wielded by the state for the sake of the folk community. Indeed, given the pervasiveness of technique in modern civilisation, only such a powerful actor such as the state would be capable of reining in technology and restraining its deracinating and culturally destructive tendencies.

It’s important to note that Freyer did not make the association between technological or scientific advancement and liberal or progressive ideas that is unfortunately still common in our society. Instead, as I mentioned in response to an earlier question, he combined an embrace of technological-scientific modernity with a rejection of political modernity. Consequently, he has been labelled a “reactionary modernist”. His project was not to turn back the clock to before modernity, but to imagine it in a different form.

Is there a connection between Freyer’s ideas and contemporary right-wing populism and identity politics?

Freyer’s work has not had much of a direct impact on rightism in the English-speaking world. He is not as well-known as Spengler, Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, and other such figures. Only a couple of his works have been translated (Revolution from the Right and Theory of Objective Mind), and there is little in the way of secondary literature written about his work. Exceptions are The Other God that Failed, a work of mainstream academia which extensively covers his life and work, Jeffrey Herf’s discussion of him in Reactionary Modernism, and Lucian Tudor’s essay on Freyer’s concept of community. However, there are some similarities between his ideas and those of contemporary rightists. These similarities doubtless arise in part because the right has increasingly been influenced by thinkers of the Conservative Revolution, but I think that the more important reason is because we are living through similar conditions as those in which the ideas first arose. Europeans have suffered a tremendous loss of prestige over the past few decades. Our culture has become decadent, our economies are failing, our people are atomised and uprooted, and our elites are either unconcerned for our welfare or they are actively hostile towards us. Our societies are changing rapidly in ways that we don’t like. In short: liberal-democracy is undergoing a crisis of legitimacy. The difference is that this crisis is not simply a German one, but extends to pretty much everywhere in the West.

As for the ideological similarities. Firstly, the focus has once again begun to shift away from notions of individual rights or free market capitalism and towards the notions of people and nation, considered as groups united by ties much more profound than common citizenship or adherence to “common values”. Secondly, the continuing failures and manifest absurdities of the liberal-democratic system (which seem to get worse by the day) are bringing home to rightists that radical change is needed if our peoples are to survive. We can’t simply tinker with the system to make things alright again, since all of our historical institutions have been occupied with people who are determined not to allow dissent, and so there is no path for piecemeal reform: there are too many leftists and liberals with a lot to lose. Consequently, there will have to be changes in the legitimating ideology of the state, in the law, in economic policy, migration policy, and other areas. These changes would be so dramatic that they could be called “revolutionary”. But at the same time they are “conservative”, in that they appeal to what is essential in the history of the West, without merely trying to reinstate older forms that are no longer appropriate to our time. In an age like this, it might be worthwhile to take inspiration from the works of thinkers such as Freyer, who grappled with fundamentally similar issues to the ones we are facing. Although it should be stressed that we can’t be content to adopt Freyer’s views wholesale. It is more the spirit of the enterprise that counts. Like Freyer and others thinkers in the Weimar Republic, we can be inspired by the past, but ultimately will have to innovate to suit our own conditions.