Tage Lindbom is a thinker situated within the Traditionalist school and connected to conservative and right-wing political thought. Although he was not directly part of the Conservative Revolution movement, his political ideas are noteworthy in that context. In the study of Traditionalism and right-wing politics, the article “Sufi Traditionalism and the Radical Right” by Gulnaz Sibgatullina and Benjamin R. Teitelbaum stands out as an important source.

Tage Lindbom is an interesting figure within the Traditionalist school. For readers unfamiliar with him, could you introduce him briefly?

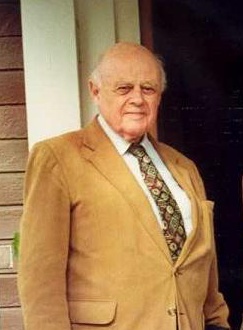

Lindbom, 1901-2001, was a Swedish philosopher and convert to Sufi Islam via the Traditionalist School and the tariqa of Swiss philosopher Frithjof Schuon. He spent much of his life on the edge of the sociopolitical elite in Stockholm, and so he kept his conversion to Islam—profoundly uncommon at the time for a ethnic Swede—a secret. His affiliation with religion in general and a Traditionalist-style Sufism in particular expressed itself instead through his books. He wrote over twenty books between 1951 and 2004, with major titles being Sancho Panzas väderkvarnar [the Windmills of Sancho Panza] and Demokratin är en myt [Democracy is a Myth]. A common thread running through them was the claim that liberalism, democracy, and secularism represented a perverse human attempt to replace god and the sacred through reason and engineering. Toward the end of his life, Lindbom attracted two circles of younger followers; one more interested in his religious practice and included often mixed-background Muslim men attracted to him as an icon of a potential Swedish Islam, and another attracted to his anti-modern politics and which included some future leaders of the Swedish radical right.

Lindbom served as an archive director and library manager for the Swedish Social Democratic Party and was an active intellectual in various cultural institutions. Over time, however, he shifted toward “radical conservatism.” What dynamics lie behind this profound transformation?

The best insights we have come from Lindbom’s autobiographical tellings. He describes his early move toward Social Democracy as having come out of an earlier attraction to communism—a move which, in turn, was born out of a tragic childhood absent his biological parents, filled with contempt for his adopted parents, and which found an early channel for anger in a communist movement that, as he put it, was essentially a brotherhood devised to destroy fathers. Yet, he would say that he lacked the unyeilding anger that communism required, and when age began to moderate his politics, and when his success as a student at Uppsala University began to open professional doors to him, he moved into the beuracracy of the Social Democrats—which, given that they were and would remain the dominant social and political force in Sweden for much of the twentieth century, meant that he was entering Sweden’s managing class. But the seeds of his exit from democratic socialism and into a form of reactionary conservatism were there from the start. While his party colleagues were focused on economic policy, he thought this focus didn’t account for all of human needs (or that human needs ought be thought of as principally material in general), and so he first advocated an interest in psychology, then “culture”–both of which were avenues for conceiving of people as more mysterious than what socialism was interested in. This already began to make him an outsider in his party. Eventually, further, he would think that it wasn’t psychology or culture, but spirituality and religion that understood humanity and the universe, and that these things were antithetical to the secular managerialism that filled the dreams of Social Democrats. Having arrived at these inferences, he began to embrace a spirituality that he had defined as essentially anti-liberal, anti-modern, and anti-democratic.

What was Lindbom’s contribution to right-wing thought in Sweden? Could you outline his main ideas and how they were received intellectually and politically?

Lindbom bolstered an expressly anti-modernist strain of radical rightwing thought in Sweden. He served as a bridge between the old Traditionalists like Frithjof Schuon and Kurt Almqvist (the latter being another early Swedish member of Schuon’s tariqa) and factions of the far right who, while not Traditionalists, still used ideas common in Traditionalism, like the anti-modernist, anti-liberal French New Right. Indeed, many of his politically-minded younger followers would go on to support, not Nazism or skinhead white nationalism per se, but French thinkers like Alain de Benoist and Guillaume Faye—they would be the intellectuals of the Swedish radical right.

Ideas of Lindbom’s that lived on here include criticisms alledeging that liberalism’s professed twin objectives of liberty and equality concealed the fact that it only pursued one of those objectives—equality—and that it would never rest until sameness, homogeneity in all ways, had been achieved within its domain. Also the claim that the real anecdote to things like feminism, multiculturalism, and globalism isn’t capitalism, fascism, or anything like that, but religion and spirituality.

Are there any interactions or thematic parallels between Lindbom and conservative revolutionary thinkers such as Spengler, Jünger, or Heidegger? If so, in what areas?

Yes. Not only is there the obvious skepticism of liberalism and progressive modernity, there is the more specific allegation that society is in the process of decline rather than improvement, and that this decline is most apparent in the trajectory of social institutions. Spengler famously saw major public institutions as being born out of a declining cultural vitality—society founds institutions to bolster cultural values and norms that are no longer being maintained organically (because the culture that bore them is disintegrating). Lindbom doesn’t articulate the same genealogy for this process, but he tracks the decline of society in the ways that institutions like the church are, for him, simply manifesting secular materialism rather than opposing it. That he seeks escape from all of this, not in public life, but in the hidden corners of the world—in esoterica, which Traditionalism explicitly embraces—aligns him with the Ernst Jünger of the Forest Passage (Der Waldgang).

To what extent can Lindbom’s influence be felt in contemporary Swedish intellectual and political right-wing circles?

It’s hard to say with any certainty. He and his distinct brand of anti-modern, anti-liberal thought certainly attracted a group of activists who would go on to contribute to an intellectual wing of the Swedish far right. These were people like Jonas De Geer, who was deeply radical but who wasn’t a militant neo-Nazi or a rightwing populist. But he also may have provided intellectual cover for the Swedish nationalist right and ultraconservative Islam to mix. One of his followers who was primarily interested in his Islamic teachings and who was of mixed Iranian-Swedish background was for a period of time welcomed and featured in radical white nationalist circles and publications—the pretext for this collaboration was that reactionary European nationalism and Islamism were both anti-modernist forces and therefore natural partners. Measuring that influence and its legacy is hard—perhaps time will clarify it—but we should note as well that his books, The Myth of Democracy in particular, reached a wider international audience of anti-liberal and anti-modernist thinkers (like Olavo de Carvalho in Brazil, who told me he’d read the book).

In a Europe where Islamophobia is on the rise, how might Lindbom’s understanding of Islam serve as a counterexample? Could it offer a new perspective on religion and identity in Europe?

Through his person and biography as much as his thinking, Lindbom seemed to signify the possibility of a distinctly native Islam to some of his followers. He was drawn to Islam, not because he thought other faiths were lacking truth or inspiration, but because he saw it as the most vibrant of religious practices, host to genuine spiritual masters. It was just a pathway to something, one of multiple. But in thinking of Islam in that way, it meant that it could be also a pathway to an authentic Swedishness—a Swedishness defined by spirituality and an enchantment of life that Christianity no longer could offer. That, at least, is the rationale of his followers who looked to him to provide all of these things. Whether that’s true or not—whether he actually envisioned himself demonstrating something like that—isn’t altogether clear to me. He didn’t talk much about Swedish nationalism or ethnic separatism. But we do know that at least some Muslims in Sweden were longing for such a figure, such a lifeway, and maybe that story isn’t over, even if Lindbom’s life is.