I have long been interested in the art of miniature, both theoretically and practically, both in the context of the Turkish painting tradition and traditional arts. I try to closely follow various miniature traditions around the world and in this context Indian miniature has a unique place among all other traditions. The Musawwir exhibition (Ojas Art Gallery) caught my attention with the approaches to miniature by artists from different backgrounds. We had an extensive conversation with the curator of the exhibition, Khushboo Jain, about the Indian miniature and the artistic possibilities it offers

Let’s start by getting to know you.

I am a native of Jaipur, Rajasthan, working as an independent curator and writer. My deep-rooted passion for history and art shapes my exhibitions, allowing me to explore themes such as politics, socio-economic landscapes, and the incorporation of Indian traditions into contemporary discourse. My primary areas of interest and research include miniature art, Tibetan art, and the cultural geopolitical happenings along the “Silk Road” belt.

Having grown up in Jaipur, miniature paintings have always been a part of my life. Coming from a Jain family, I was surrounded by scriptures and paintings in temples that featured these exquisite works. In my early teens, I shifted my painting style to embrace the miniature form. During a competition, the jury appreciated my work but advised me to consider pursuing a more modern style, noting that traditional miniature art was not popular and seemed relegated to museums as an outdated form. This childhood experience, coupled with my upbringing, has profoundly influenced my curatorial journey.

Each visit to art galleries highlighted the absence of miniature works, motivating me to bring them to the forefront. The writings and interviews of B. N. Goswamy, as well as his panel discussions at the Jaipur Literature Festival, have inspired me greatly in my curatorial endeavors. My educational background in history, extensive research in miniatures, and experiences working with individuals from the Middle Eastern region in my previous role have deeply engaged me with the world of miniatures.

Could you tell us about Indian miniature art? How does it differ from the miniature art of other cultures?

Indian miniature art can only be told in its barest summary. From the eleventh to the nineteenth century, miniatures kept running in different courses, paces and energies. Several streams of development ran parallel to one another during this time. The earliest ‘miniatures’ one can speak of– at least from those that survived– goes back to the eleventh century and are found to be on palm leaf as part of Jaina and Buddhist traditions in the Indian subcontinent.

Following the rise of Islam and the establishment of power in northern India from the thirteenth century onwards, Sultanate painting emerged in and around Delhi. The Mongol invasions during the thirteenth century played a crucial role in cultural exchange, as Persian artists absorbed techniques from East Asia, enriching both Persian and Indian art. The Timurid reign in Persia further provided substantial patronage to the arts, fostering the refinement of miniature painting alongside the ongoing exchanges facilitated by the Silk Road, which allowed for the flow of artistic ideas and materials between regions.

By the sixteenth century, artistic patronage flourished, with emperors themselves directly supporting various painting schools, notably within the Mughal tradition. This period also saw the blossoming of styles in the Rajput school of Rajasthan, the Pahari regions, and the Deccan in southern India. The Safavid expansion into northern India under Babur significantly influenced the Mughal school of painting, leading to a seamless integration of styles that reflected both Persian and indigenous elements.

Subsequently, the arrival of the British led to the emergence of what is termed the “Company school of painting,” which involved Indian artists creating works for British patrons and officers of the East India Company. However, with the advent of the British Raj, Western aesthetics effectively overshadowed traditional practices as they increasingly became viewed through an orientalist lens. This shift led to the marginalisation of detailed, labour-intensive miniatures, which were relegated to the status of ‘tourist kitsch’ and ‘exotic imagery’ designed to satisfy the growing Western appetite for artefacts, thus transforming rich cultural expressions into mere commodities devoid of their original significance.

Despite these challenges, the spirit of miniature painting has proven to be remarkably resilient. In recent years, there has been a resurgence of interest in miniature painting that we can see.

However, it is important to note that the practice of musawwari, iconographically, has always been open, engaging in new dialogues and exchange of ideas. This includes influences from Chinese and Central Asian landscapes and figures in Timurid, Herat, as well as European prints within the Mughal court. This exchange has played a key role in developing the visual language of musawwari. In fact, this openness is closely related to the current stylistic evolution of miniature art, as it transcends geographical boundaries and intersects with various cultures, remaining relevant through its pluralistic engagements.

I went about elaborating much about the history but that’s relevant in understanding the miniature artform and its evolution.

In terms of style and techniques– Indian miniature paintings, particularly those from the Mughal period, utilize a blend of bold colors and fine, delicate lines influenced by Persian artistry. In contrast, Persian miniatures emphasize balanced compositions and intricate detail without the use of perspective, often depicting subjects from a more limited narrative scope.

When it comes to subject matter, Indian miniatures typically incorporates religious icons and narratives from Indian epics like the Ramayana and Mahabharata, as well as the histories of dynasties. This differs from Persian miniatures, which often focus on royal hunts, battle scenes, and typically emphasize Persian mythology and poetry.

Indian miniature art developed amidst a rich cross-cultural environment, blending Indian, Persian, and later European styles, particularly during the Mughal Empire. In contrast, Persian miniatures largely stemmed from courtly traditions and maintained their identity even as they absorbed elements from Chinese and later European influences.

Mughal miniatures reflect a systematic workshop collaboration, with different artists specializing in various tasks to produce a singular piece. This collaborative aspect is similar yet distinct from the Persian approach, which also involved collective efforts but was often more centralized in terms of individual artist recognition.

In its aesthetic orinciples, Indian miniatures often display a greater emphasis on depiction of lively scenes, emotional expressions, and natural flora, showcasing a connection to nature prevalent in Indian culture. Persian artworks, while also detailed, tend to be more rigid in formality and lack the same depth of emotional expression found in Indian traditions.

In miniature art, the lack of perspective and shadow—do you see this as a limitation compared to other art forms, or does it provide an advantage for showcasing your creativity? How do these traditional constraints influence your artistic expression?

In discussing the absence of perspective and shadow, I view this aspect as an advantage, rather than a limitation compared to other art forms. The lack of perspective allows artists to concentrate intently on detail and color, exploring intricate patterns and vibrant palettes. This approach leads to the creation of visually striking pieces that captivate viewers through richness and precision. Not being bound to realistic representations lets artists utilize colors that reflect personal or cultural narratives more expressively, enhancing storytelling depth.

The absence of these traditional constraints encourages a playful and imaginative interpretation of subjects, granting artists the freedom to innovate with form and structure. This flexibility fosters unique artistic voices, enabling the creation of works that authentically represent individual styles and cultural identity. Miniature art allows artists to communicate cultural heritage, spirituality, and folklore while maintaining a visual language resonant with their specific contexts. By prioritizing emotional expression and spiritual themes, Indian miniatures uphold cultural values rather than conform to physical space illusions.

The advantages of lacking perspective and shadow present artists with opportunities to deepen their expression, engage viewers, and explore imaginative narratives. Instead of limiting creativity, these constraints lay the groundwork for rich artistic exploration, resulting in multifaceted engagement with culture, symbolism, and personal expression.

In today’s world, is there an exotic or orientalist approach to miniature art, or is it evolving into a new form of expression that merges with modern painting? What are the theoretical resources to understand miniature art?

That’s a very good and imporatnat question.Regarding the existence of exotic or orientalist approaches to miniature art, it is crucial to note that while the resurgence of contemporary miniatures is worth celebrating, traditional practices are often overshadowed by their modern counterparts. There is a tendency to repackage orientalism, framing traditional art not as serious cultural expressions but rather as commodities designed to satisfy Western appetites for exoticism. This dynamic risks diminishing the intricacies of miniature art and undermining its historical context while further alienating traditional practices from their cultural significance.

Contemporary miniaturist practice has often been positioned within a larger trend, gaining recognition particularly for addressing identity politics and cultural satire, sometimes critiquing their cultural values. Within this dominant framework, traditional musawwari rarely receives appropriate consideration on a global scale.

However, traditional forms are as relevant today as their modern interpretations. This exhibition intentionally places contemporary works alongside those of established masters to break down such categorizations.

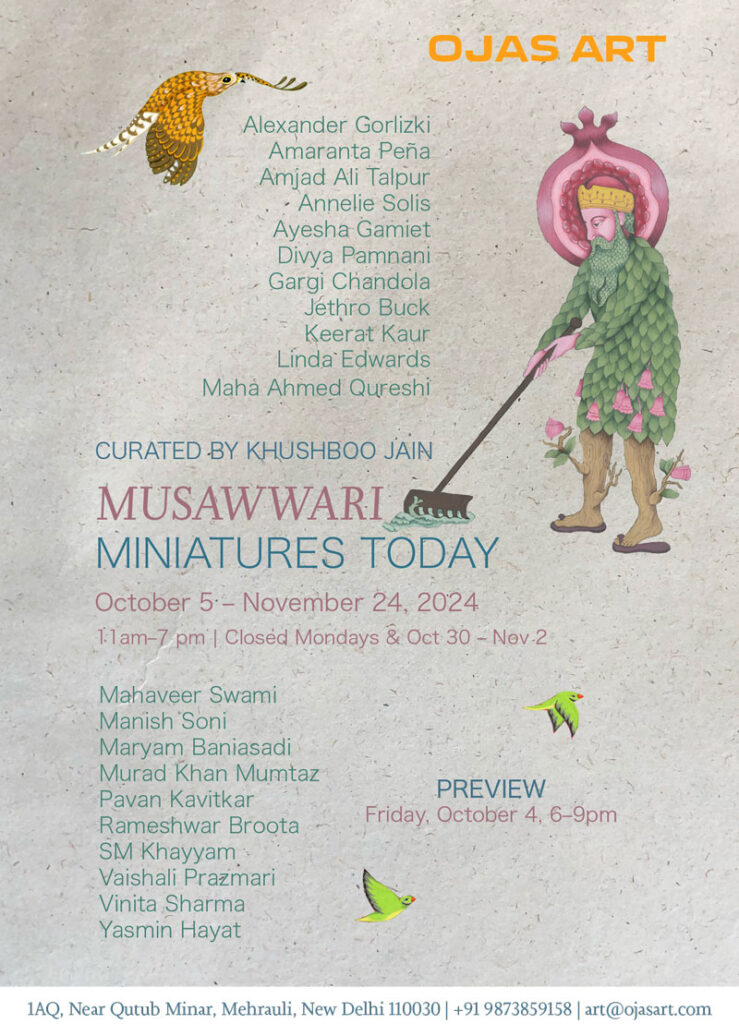

You curated the Musawwiri exhibition, bringing together miniature artists from various parts of the world. Could you tell us about this exhibition and the concept behind it?

In curating the Musawwir exhibition, I aimed to highlight the cultural significance and artistic evolution embodied within miniature art. While often referred to as ‘miniatures,’ these works vary significantly in size, with some being smaller than postcards and others reaching nearly a meter in height. Despite this breadth of variation, the term ‘miniature’ remains prevalent, which raises questions about its appropriate application to this art form.

Upon exploring historical texts, particularly in Persian sources, I discovered references to these paintings as ‘musawwari.’ In Persian tradition, musawwari describes a traditional painting style associated with miniature art across Central and South Asia. The painters, referred to as ‘musawwirs,’ embody the art’s essence. This led me to question why we do not reclaim the term ‘musawwari’ in contemporary discourse, especially given the colonial overtones associated with the term ‘miniature.’

By redefining the art form through the context of musawwari, we acknowledge its layered history and cultural significance. The practice has always been open to engaging with new dialogues and exchanging ideas, including influences from Chinese and Central Asian landscapes, and European prints within the Mughal court.

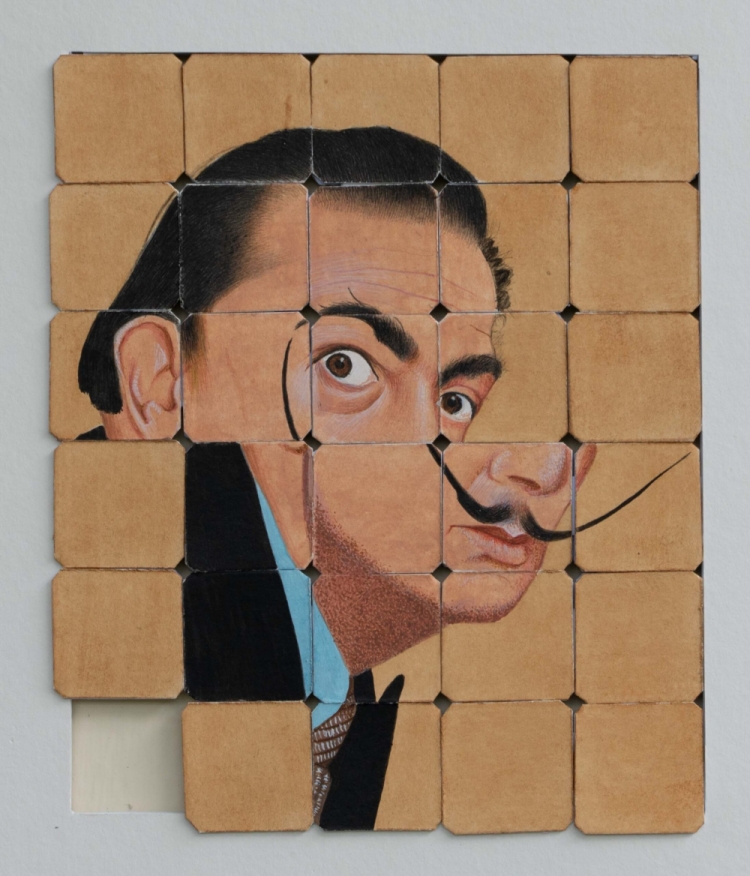

The exhibition features twenty-one talented artists, each presenting unique perspectives shaped by their personal experiences and cultural backgrounds. This new generation actively explores and redefines miniature art, blending traditional techniques with contemporary themes that reflect both heritage and personal narratives. They break new ground by experimenting with form, iconography, and materials, navigating the complexities of globalization and socio-cultural shifts.

Today, miniature painting transcends its classic formats, embracing new scales and methods while retaining its foundational elements. Contemporary artists often address complex themes related to geopolitics, nationhood, post-colonial sensibilities, and personal identities, while traditional forms continue to depict stories from epics, religious texts, and poetry.

The Musawwari exhibition concept underscores that musawwari is far more than a relic of the past; it remains a living, evolving tradition. This exhibition transcends a mere celebration of miniature art’s revival; instead, it actively engages with its contemporary dynamics and global development. The takeaway is a recognition of the art form’s power to address modern concerns while maintaining ties to its roots. It is crucial to appreciate that traditional miniatures are an integral part of this contemporary narrative, which unfortunately is often forgotten in the confines of museums.

It also leaves a note on bluring of boundaries around miniature art leaving the audience with a questions as what is tradtional miniature, what is inspired miniature art and what is an attempted miniature art.