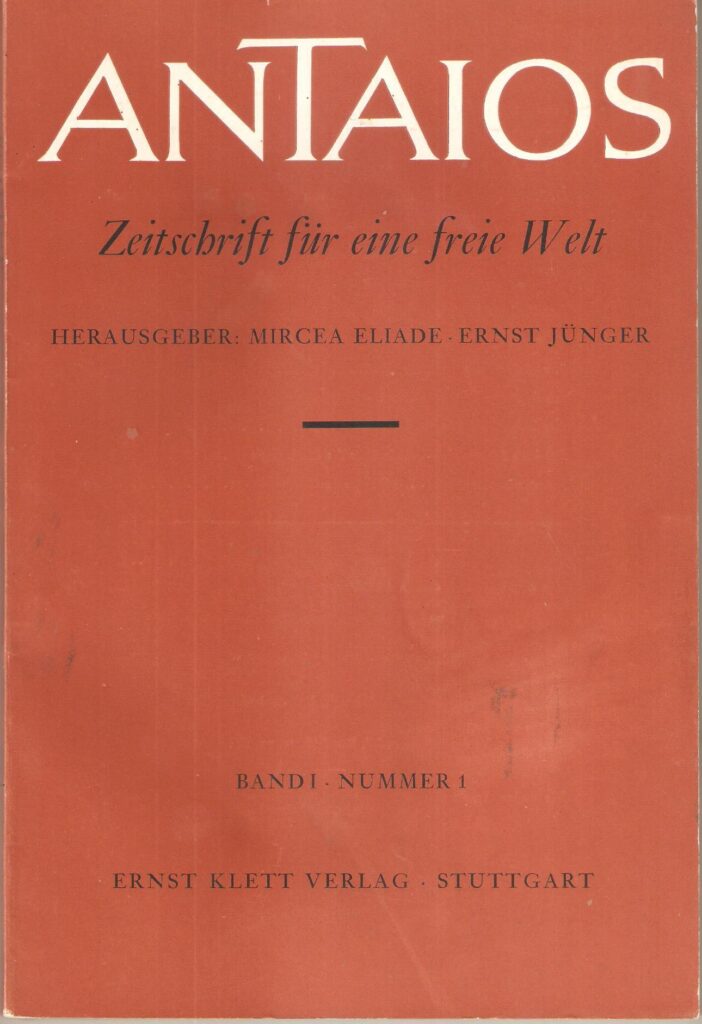

It was no surprise for me to come across Traditionalism in my research on Conservative Revolutionism. While analysing how they influenced each other and whether there was any communication between them, I came across Antaios. This magazine, edited by Ernst Jünger and Mircea Eliade, was an important platform where high-level conservative intellectuals came together. We recently discussed figures such asAntaios, Jünger and Julius Evola with Luca Siniscalco.

Let’s start by getting to know you.

First of all, I want to thank you very much for your interest in my studies and for offering me this dialogical space on your great intercultural avant-garde platform.

I’m Luca Siniscalco, currently a PhD student in Transcultural Humanities at the University of Bergamo, in co-tutelle with the German Justus Liebig University of Gießen. My research project is provisionally entitled “The Event of the sacred in post-secular age. Encounters with Hans-Georg Gadamer’s hermeneutics, Hermann Nitsch’s and Anselm Kiefer’s art”.

I’ve previously been Adjunct Professor of Aesthetics at the University of Milan (a.y. 2021/2022) and at eCampus University (a.y. 2019/2023). Currently, I’m also lecturing on Study Skills at the European School of Economics (Milan Campus) and on Contemporary Philosophy in the Academic Project UniTreEdu.

My research interests primarily concern contemporary German philosophy and literature, aesthetics, contemporary art, symbolism and philosophy of religion. In this context, I devoted my Master’s Thesis in Philosophy to the journal “Antaios”, which I know represents for you and your audience a relevant source of interest. I’ll soon offer a brief introduction to it.

Beyond academia, I’ve been involved, from a relatively young age, in the study, discussion and editorial promotion of the thought of erratic and “untimely” (in Nietzsche’s sense) authors, with particular interest for Perennialism, Integral Traditionalism and Conservative Revolution. I’ve already developed a decent personal production on these currents of thought, on which I’ve been coordinating several editorial, cultural and even artistic projects.

What is the birth and importance of the Antaios Journal? How did Eliade and Jünger’s paths cross here? How can the impact of this journal on the generations that followed it be evaluated?

The “Antaios” journal was published by the German publishing house Klett-Cotta from 1959 to 1971 under the direction of the German writer and philosopher Ernst Jünger (1895-1998) and the Romanian historian of religions Mircea Eliade (1907-1986).

The genealogy of the cultural project is quite complex, and here I can just summarize some relevant facts which explain how Eliade’s and Jünger’s paths crossed in this creative and fascinating direction.

It seems that the intention to collaborate on a journal came from Jünger, who had already known and appreciated Eliade thanks to the mediation of his friend Carl Schmitt. The two – Jünger and Eliade – initially established an epistolary contact, which led to their first meeting in 1957, five years after their initial contact.

At that time, Jünger’s publisher and friend, Ernst Klett, wanted to promote a conservative journal characterized by a high cultural level and an international perspective. His cultivated nephew kültürlerarası avangart platformunuzda , Philipp Wolff-Windegg, was chosen as the editor-in-chief, but more famous and distinguished intellectuals would have been appointed to direct the project. Jünger and Eliade, in dialogue with Klett, thus became the founders, as well as the theoretical inspirers and nominal editors, although Wolff-Windegg accomplished all the practical tasks.

The role of Wolff-Windegg, as underlined by Hans-Thomas Hakl (the author of the only significant essay published on the history of “Antaios”, in German: ‘Den Antaios kenne und missbillige ich. Was er pflegt, ist nicht Religio, sondern Magie!’ Kurze Geschichte der Zeitschrift ANTAIOS, in “Aries”, 9, 2) was pivotal: he passionately and carefully did the whole “dirty work” required by such a vast project, while Jünger and Eliade mainly represented an assurance of cultural quality and a resource to attract collaborators from all over the world who were willing to donate their best thoughts and ideas to the journal. Among them, I can here recall just the most famous names: Friedrich Georg Jünger, Emil M. Cioran, Roger Caillois, Cristina Campo, Henri Micheaux, Denis de Rougemont, Henry Corbin, Raimon Panikkar, Leopold Ziegler, Frithjof Schuon, Julius Evola and Gherardo Gnoli.

These – and many other – eminent names couldn’t prevent the end of the journal in 1971, mainly for economic reasons – the sold copies were not enough to sustain the editorial effort.

What remained – and remains – is the cultural and existential tension of the project, which is synthetized in a lyrical expression by Ernst Jünger: “Today, as Kant’s bright sun is becoming duller, perhaps the dark one of his fellow Königsberg citizen, Hamann, is rising“. The purpose was, to put it more clearly, to challenge mainstream European thought, which, in the ’60 was dominated by Marxism and by the central role, as disciplines considered capable of exhaustively interpreting reality, of political science, sociology and materialistic psychoanalysis. Instead, “Antaios” evoked a process of “Gods resurrection”: an interpretation of the world through the cultural “weapons” furnished by mythic-symbolic hermeneutics (see on that my article Antaios: A Mythical and Symbolic Hermeneutics, in “Forum Philosophicum”, vol. XXV, n. 1, 2020).

Wieland Schmied perfectly understood this in his 1960 article Der Gegenwart eine neue Dimension gewinnen – Zu zwei neuen Zeitschriften, where he stated: “Antaios” is a journal directed against our age – against the alienation and uprooting of modern man. The authors gathered here manifestly rebel against the spiritual impoverishment caused by abstract, conceptual thinking, and oppose the formal, bloodless language of the specialized sciences with the symbolic language of a world of images that has been removed. Here one moves in the footsteps of now-buried sources“.

To objectively measure the theoretical impact of “Antaios” is a difficult task. On one side, the end of the project and the lack of studies devoted to it – apart from the solitary adventurous journey of H.T. Hakl, who deeply inspired my research – seem to certify its limited relevancy. But, looking at it through a deeper lens, it is possible to recognize some direct (and indirect) fruits of this experience, which try – or pretend – to maintain the “spirit” and cultural program of the journal. Among them I can mention the journals “Scheidewege. Zeitschrift für skeptisches Denken” (from 1971) and “Merkur” (an already existing monthly magazine, published by Klett Cotta from 1968, endowed with a similar conservative perspective and which is still alive today), and the homonymous publishing house Antaios, which is especially focused on metapolitics, with connections to the so-called Neue Rechte.

Furthermore, as I’ve recently argued in an essay devoted to Eranos (in the collective book Viaggio a Eranos. Il ritorno degli Dèi nel XX secolo, Bietti, Milano 2024), it is possible to identify in 20th Century Europe a broader phenomenon of intertwined journals, symposia and cultural milieus, which, despite their differences and peculiarities, shared in the “Heart of Darkness” of the Short Century the ambition of searching for “Another Modernity” – Another Beginning (Neuer Anfang) to adopt Heidegger’s lexicon. This was based on the valorization of myth, symbols, esotericism, and the qualitative inspired languages of arts, refusing subordination to the schemes of rationalism, materialism, positivism and secularization. Connected to this perspective is the development of an analogical approach to phenomena aimed at bringing together interior and exterior, subject and object, idea and matter, transcendence and immanence, fragment and totality. The intention of Jünger, Eliade and the many collaborators who participated in this intellectual journey was indeed to approach the microcosm as a pulsating life, holistically grasping the transcendence in the fragments, finding in the meshes of reality a plural and multidimensional ontology, contemplating the hierarchy of forms which always leads back to the ineffable Origin from which they all spring.

Along this path we encounter also other editorial experiences, such as that of “Conoscenza Religiosa”, an Italian journal founded by Elémire Zolla, and the “Zeitschrift für Ganzheitsforschung”, headed by the Austrian Walter Heinrich, just to mention two of them. Even more broadly, the experience of “Antaios” could be also put in dialogue with the significant growth of interest that the study of Western esotericism has aroused in recent decades in the academic sphere at an international level. Going back in time, it would be interesting, in terms of the history of ideas, to compare it with the esoteric cultural circles of the early twentieth century – I am thinking, for example, in Italy, of the congressional activities of Decio Calvari’s Independent Theosophical League and the operative (and editorial) magic initiatives of Gruppo di Ur.

This hidden cultural history of the West still requires researchers, scholars, commentators, and even successors.

What were the prominent topics in Jünger’s writings in the “Antaios” Journal? Which themes did he develop his thoughts on?

During its decade of publication, Ernst Jünger published 17 essays in “Antaios”. Most of them first appeared originally in the journal but were subsequently re-elaborated and autonomously published by the German writer. On the pages of “Antaios”, for example, we can read fundamental sections of An der Zeitmauer (At the Time Wall), but also the core texts of the future books Maxima-Minima and Annäherungen. Drogen und Rausch (Approaches. Drugs and Altered States).

The topics are therefore various: they are concerned with the problem of modernity and nihilism, the existential condition of modern man, but they also treat more disengaged topics, especially in the numerous travel diaries. Considering Jünger’s current existing bibliography – at least in European languages –, discovering these articles doesn’t open extremely new scenarios in the context of Jünger’s studies.

What is particularly relevant, in my opinion, is the context of publication and the resonance of Ernst Jünger’s texts with the whole “Antaios” “program”. Reading these articles within this milieu emphasizes the centrality of myths, symbols and sacredness in Jünger’s view – not in an old-fashioned or reactionary way, but as fundamental counterparts of logos in the comprehension of reality and in the enhancement of human life experience. This Jünger, motivated to search for the beauty of the holiness within the manifestation of nature, cultural traditions, literature expressions, and even psychotropic experiences, needs to be integrated with the most famous heroic, militaristic and politic surface of his cultural identity.

It is quite remarkable that the conservative revolutionary Jünger and the traditionalist Eliade come together on this platform. In which points do you think conservative revolutionaries and traditionalists unite and in which issues do they differ? On what intellectual grounds did this meeting take place?

A preliminary clarification is necessary. The relationship itself between Eliade and Traditionalism has been widely debated in literature, often leading to radically heterogeneous outcomes. By improperly summarizing an interesting and varied debate, I believe it is possible to identify two essential positions: on the one hand, the subsumption of Eliade, with all the distinctions and gradations of the case, to the traditionalist strand, with the accentuation of the consistency of his positions with those of the main exponents of Tradition thought and of the esteem he repeatedly declared towards them; on the other hand, the prominence given to Eliade’s academic requirements, to his scientific methodological approach and his rejection of the pessimistic conception of historical degeneration typical of traditionalism, as well as the very absence of the notion of Tradition, at least in the “strong” sense, in his work.

Avoiding this specific debate, and coming to your question, what is relevant is that the project of “Antaios” indeed hosted articles by Eliade (and other “colleagues”, such as Corbin, de Martino, Kerényi and Zaehner), representatives of Konservative Revolution (Jünger brothers, but also Niekisch) and several traditionalists (among others: Schuon, Evola, Zolla, Campo, Pio Filippani-Ronconi). Considering the non-political direction of the journal, what was shared by all of them was the sensitivity which I’ve already defined as “mythic-symbolic hermeneutics”: an attempt to re-sacralize the human gaze on reality and refer to the original religious, esoteric, and symbolic sources as a relevant and actual toolkit to read, deepen and even transform reality. The significant theoretical differences between their perspectives become secondary with respect to the existential relevance of this task and the common antimodern perspective. This engagement was shared according to the typical conservative-revolutionary mind-set: to preserve tradition not by ideologizing and reifying it, instead by dynamically making it actual and alive. The destination was depicted by Jünger as the Great Encounter at the wall of time, by Eliade as the coincidentia oppositorum conquered in the religious unitive and cosmogonic paths, by several authors through different symbols and images: but we are always dealing with a spiritual conjugative realization conceived outside the classical metaphysical and theological dualistic forms.

Also, what can you say about the relationship between Evola and Jünger? Did Evola communicate with Jünger? How did they influence each other intellectually?

From a biographical point of view, we are only allowed to follow some rare and disguised traces, which are, however, relevant enough to recognize a significant and fertile relationship.

Jünger is only one of several members of the German and Austrian Konservative Revolution with whom Evola was in contact from the end of the 1920s. They probably never met in person, but some letters testify to their direct acknowledgment and a good intellectual exchange (these letters have been recently published in Julius Evola, Fuoco Segreto. Lettere, interviste, documenti, testimonianze, inediti, Edizioni Mediterranee, Roma 2024). This connection culminated in Evola’s collaboration with “Antaios”: five of his articles were published between 1960 and 1970 in the Klett-Cotta journal – although it is more probable that they were not requested by Jünger, but rather agreed with a collaborator of the publishing house, with whom Evola published the German edition of his Metaphysics of Sex. On Evola’s collaboration with “Antaios” see Julius Evola, Antaios (1960-1970), introduction by Hans Thomas Hakl, edited by Luca Siniscalco, Fondazione Julius Evola/Pagine, Roma 2019.

We also owe to Evola the discovery and dissemination of Jünger in Italy. The Roman traditionalist wanted to translate Der Arbeiter (The Worker), his favorite text by Jünger because of the heroic realism embodied in the Form of New Objectivity and in a radical metaphysics of will. Not finding an agreement, he devoted to it a monographic text, full of quotations: L’“Operaio” nel pensiero di Ernst Jünger (The “Worker” in the Thought of Ernst Jünger; introduced by Marino Freschi, Edizioni Mediterranee, Roma 1998).

Evola also translated, with the pseudonymous of Carlo d’Altavilla, At the Time Wall (published in 1965 by Volpe), despite not appreciating the “second” Jünger, whom he considered, as expressed in a review, too involved in a sort of escapist and phantasmatic worldview: “The book – writes Evola (“Al muro del tempo”, in Ricognizioni. Uomini e problemi, Mediterranee, Roma 1974) –, contains here and there valid insights and considerations, mixed, however, with fantasies and dubious speculations. In terms of systematicity and conclusiveness it is not at the level of The Worker. Above all, in order to seriously address the metaphysics of history (conception of time, doctrine of the four ages of the world, eschatology, etc.), personal views, even if of a shrewd and artist’s mind, cannot suffice; instead, it is necessary to refer to an objective, traditional knowledge, as did, for example, a René Guénon and his group and as we ourselves have tried to do, dealing with similar problems”.

It is hard to hypothesize a reciprocal influence: we even don’t know if Jünger read any of Evola’s books – and it seems that Evola found in Jünger confirmation of his already elaborated positions, rather than an impetus to modify, reshape, or revise them. However, some strong theoretical affinities – too numerous to be exhaustively enumerated – demonstrate a common deeply-rooted horizon. We can consider, for instance, their approach to the question of nihilism, their youthful voluntaristic titanism, the fascination for myths and symbols, their interest in radical subjectivities (the Anarch for Jünger and the “differentiated man” for Evola), and the fascination with apolitia. These shared interests and perspectives still requires further studies and research to fully explore their implications and interconnections.